Martina Deuchler (born 1935 in Zurich) is a Swiss academic and author. [1] She was a professor of Korean studies at the SOAS University of London from 1991 to 2001.

Martina Deuchler (born 1935 in Zurich) is a Swiss academic and author. [1] She was a professor of Korean studies at the SOAS University of London from 1991 to 2001.

Martina Deuchler developed her interest in Korea by way of Chinese and Japanese studies. She was educated in Leiden, Harvard and Oxford, at a time when Korea was still hardly known in the West. As one of the first Western scholars, Martina Deuchler studied Korean history and published a number of key works: Confucian Gentlemen and Barbarian Envoys (1977), The Confucian Transformation of Korea (1992), and Under theAncestors' Eyes (2015). With her original scholarly work, combining history with social anthropology, Martina Deuchler created a framework for exploring Korean social history, within which she continues to research landed elites and their perception of the historic changes in East Asia at the end of the nineteenth century. As Korean studies emerged as an academic field in the second half of the twentieth century, Martina Deuchler, generously supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, contributed to the networking among Korea specialists isolated in a few European universities and was one of the founding members of the Association for Korean Studies in Europe (AKSE) in 1977. She participated in numerous scholarly workshops and conferences a few of which she herself organized. As Professor of Korean Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London from 1988 to her retirement in 2000, she dedicated herself to educating future generations of Koreanists and advancing Korean Studies as an academic field. She continues to be active as researcher and consultant.

Martina Deuchler studied classical and modern Chinese language and history as well as classical and modern Japanese language and literature at Leiden University, NL, from 1954 to 1959. She received her B.A. in Chinese and Japanese with honors in 1957. From 1959 to 1963 she continued her studies of modern history of China and Japan as a scholarship student in the Regional Area Program in East Asia of Harvard University. Her advisers were Prof. John K. Fairbank and Prof. Edwin O. Reischauer. She received a PhD in History and Far Eastern Languages with a dissertation entitled "The Opening of Korea, 1875–1884" in 1967. Supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, she studied social anthropology with Prof. Maurice Freedman at Oxford University in 1972. In October 1979 she presented a second dissertation (Habilitation) with the title "Confucianism and the Social Structure of Early Yi Korea" to the University of Zurich and was awarded the Venia legendi for Classical Sinology and Korean Studies.

| 1967–1969 | Research in Korea as research fellow in East Asian studies, Harvard University |

| 1973–1975 | Research in Korea as part of the SNSF project „History of Korea" |

| 1978–1988 | Elected member of the Board of the Swiss Society of Asian Studies (Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Asienkunde) |

| 1983–1986 | Member of the Committee on Korean Studies (CKS) of the Association for Asian Studies (AAS), Ann Arbor, Michigan |

| 1983–1988 | President of the Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Asienkunde |

| 1975–1988 | Teaching Korean history and language, University of Zurich |

| 1980–1983 | Member of the Joint Committee on Korean Studies of the Social Science Research Council and the American Council of Learned Societies (SSRC/ACLS) |

| 1987–1988 | Elected member of the Research Council of the Swiss Academy of Sciences, Berne |

| 1988–1991 | Senior Lecturer for Korean Studies, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London |

| 1989–1998 | Chair of the Centre for Korean Studies, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) |

| 1991–1993 | President of the Association for Korean Studies in Europe (AKSE) |

| 1991–2001 | Professor of Korean Studies, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London |

| 2000 | Member of the Visiting Committee on East Asian Studies (Board of Overseers of Harvard College), Harvard University. Responsible for the Korea program |

| 2001 | Visiting Professor of Korean History at Cornell University |

| 2002–2005 | Member of the International Advisory Committee of the Korea Foundation |

| 2004 | Member of the Visiting Committee on East Asian Studies (Board of Overseers of Harvard College), Harvard University. Responsible for the Korea program |

| 2004 | Visiting Professor, Academy of Korean Studies, Seoul |

| 2006 | Member of the Visitatie Commissie Niet–Westerse Talen en Culturen, Leiden University; responsible for the Korea program |

| 2002–2014 | Research Professor, Centre for Korean Studies, School of Oriental and African Studies SOAS, London |

| 2008–2009 | Visiting Professor of Korean History at Sŏgang University, Seoul |

This section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources .(September 2023) |

Martina Deuchler has conducted intensive research in Korea for over fifty years. Due to the fact that in the 1960s there were few historical sources on Korea in Western libraries, she went to Korea to study in the former royal library (Kyujanggak) from 1967 to 1969. The result of this two-year stay was the publication of Confucian Gentlemen and Barbarian Envoys (1977), a history of Korea's diplomatic opening by Japan and the Western powers at the end of the nineteenth century.

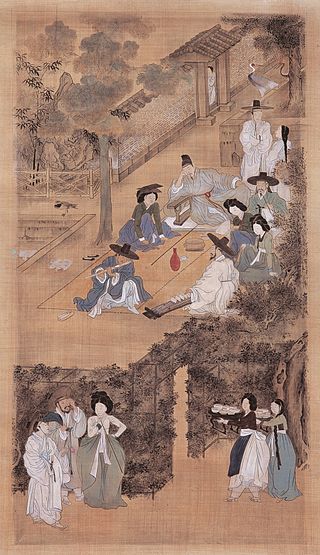

At that time, Martina Deuchler also conducted fieldwork on Confucian ritualism, especially ancestor worship. Thanks to her affinal relations through her husband, Dr. Ching Young Choe, she was granted unique access to social and religious traditions and ceremonies, rarely witnessed by Westerners, in a remote rural area in North Gyeongsang Province. She documented her observations in numerous color slides. In 1972 she moved to Oxford University to study social anthropology with Maurice Freedman. During a second sojourn from 1973 to 1975 she expanded her knowledge of Korea's social history with archival and field research. This resulted in a major, highly acclaimed work, The Confucian Transformation of Korea (1992). This book, translated into Korean and partly into Japanese, focuses on the influence Chinese Neo-Confucianism exercised on Korean society of the Joseon period (1392–1910). It documents the stages by which Neo-Confucianism, as a socio-political ideology, transformed the originally bilateral Korean society into a patrilineal one.

After many more years of research on social and intellectual history, in particular Korean Neo-Confucianism, and sustained dialogue with Korean scholars, she published Under the Ancestors' Eyes in 2015. This work argues that Korean elite society was structured on the basis of descent groups throughout its long history, and actually up to this day. In premodern Korea, therefore, it was social origin (i.e., birth and descent) rather than political office that served to identify elite status. The research materials of Martina Deuchler are since 2017 preserved in the Ethnographic Museum of University of Zurich.

In a statistical overview derived from writings by and about Martina Deuchler, OCLC/WorldCat encompasses roughly 18 works in 56 publications in 4 languages and 1,694 library holdings. [2]

| 1993 | Wiam Chang Chi-yŏn Memorial Award for Korean Studies |

| 1995 | Reischauer Memorial Lectures at Harvard University |

| 1995 | Order of Cultural Merit (Eun-Gwan, Silver Crown), Republic of Korea |

| 2001 | George L. Paik Scholarship Award (Yongjae haksulsang) der Yonsei University, Institute of Korean Studies, Seoul |

| 2001 | Citation of Appreciation for "outstanding contribution to the development of Korean Studies in the World" from Korea Foundation, Seoul |

| 2006 | Elected Corresponding Fellow (H3) of the British Academy, FBA. |

| 2008 | Honorary Member of the British Association of Korean Studies (BAKS) |

| 2008 | First Korea Foundation Award for Contributions to Korean Studies |

| 2009 | Association for Asian Studies (AAS), Lifetime Achievement Award, 2009. [3] |

| 2011 | Honorary Member of the Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch, Seoul |

| 2018 | Award Honorary degree by the Faculty of Humanities, University of Zurich |

Joseon, officially Great Joseon State, was a dynastic kingdom of Korea that existed for 505 years. It was founded by Taejo of Joseon in July 1392 and replaced by the Korean Empire in October 1897. The kingdom was founded following the aftermath of the overthrow of Goryeo in what is today the city of Kaesong. Early on, Korea was retitled and the capital was relocated to modern-day Seoul. The kingdom's northernmost borders were expanded to the natural boundaries at the rivers of Amnok and Tuman through the subjugation of the Jurchens.

Korean Confucianism is the form of Confucianism that emerged and developed in Korea. One of the most substantial influences in Korean intellectual history was the introduction of Confucian thought as part of the cultural influence from China.

Neo-Confucianism is a moral, ethical, and metaphysical Chinese philosophy influenced by Confucianism, which originated with Han Yu (768–824) and Li Ao (772–841) in the Tang dynasty, and became prominent during the Song and Ming dynasties under the formulations of Zhu Xi (1130–1200). After the Mongol conquest of China in the thirteenth century, Chinese scholars and officials restored and preserved neo-Confucianism as a way to safeguard the cultural heritage of China.

Yi I was a Korean philosopher, writer, and Confucian scholar of the Joseon period. Yi is often referred to by his art name Yulgok. He was also a politician and was the academical successor of Jo Gwang-jo.

Yi Hwang was a Korean philosopher, writer, and Confucian scholar of the Joseon period. He is considered the most important philosopher of Korea - he is honored by printing his portrait on the 1000 South Korean won banknote, on the reverse of which one can see an image of his school, Dosan Seowon. He was of the Neo-Confucian literati, established the Yeongnam School and set up the Dosan Seowon, a private Confucian academy.

Chŏng Mong-ju, also known by his art name P'oŭn (포은), was a Korean statesman, diplomat, philosopher, poet, calligrapher and reformist of the Goryeo Dynasty. He was a major figure of opposition to the transition from the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392) to the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897).

Silhak was a Korean Confucian social reform movement in the late Joseon Dynasty. Sil means "actual" or "practical", and hak means "studies" or "learning". It developed in response to the increasingly metaphysical nature of Neo-Confucianism (성리학) that seemed disconnected from the rapid agricultural, industrial, and political changes occurring in Korea between the late 17th and early 19th centuries. Silhak was designed to counter the "uncritical" following of Confucian teachings and the strict adherence to "formalism" and "ritual" by neo-Confucians. Most of the Silhak scholars were from factions excluded from power and other disaffected scholars calling for reform. They advocated an empirical Confucianism deeply concerned with human society at the practical level.

Kaibara Ekken or Ekiken, also known as Atsunobu (篤信), was a Japanese Neo-Confucianist philosopher and botanist.

James B. Palais was an American historian, Koreanist, and writer. He served as Professor of Korean History at the University of Washington; and he was a key figure in establishing Korean studies in the United States.

Yun Jeung or Yun Chŭng was a Confucian scholar in Korea during the late period of the Joseon dynasty. He was known as being a progressive thinker and for his opposition to the formalism and ritualism in the predominant philosophy of Chu Hsi. Yun Chung refused government office because he thought the Korean monarchy was corrupt, and spend his life teaching Sirhak ideas. He is known for the quote, "The king could exist without the people, but the people could not exist without the king."

Gyorin was a neo-Confucian term developed in Joseon Korea. The term was intended to identify and characterize a diplomatic policy which establishes and maintains amicable relations with neighboring states. It was construed and understood in tandem with a corollary term, which was the sadae or "serving the great" policy towards Imperial China.

Kwŏn Kŭn was a Korean Neo-Confucian scholar at the dawn of the Joseon period, and a student of Yi Saek. He was one of the first Neo-Confucian scholars of the Joseon dynasty, and had a lasting influence on the rise of Neo-Confucianism in Korea.

Choe Ik-hyeon was a Korean Joseon Dynasty scholar, politician, philosopher, and general of the Korean Righteous Army guerrilla forces. He was a strong supporter of Neo-Confucianism and a very vocal nationalist, who defended Korean sovereignty in the face of Japanese imperialism.

Mun Ik-jeom was a politician of the Goryeo period and a Neo-Confucian scholar. His given name was Ikcheom, his courtesy name was Ilsin, and his art names were Saeun and Samudang.

Ha Ryun, also spelled as Ha Yun (Korean: 하윤), was a Joseon politician and Neo-Confucian scholar, educator, and writer. He served as Chief State Councillor during the reign of King Taejong from 1408 to 1409, from 1409 to 1412 and again from 1414 to 1415. He was from the Jinju Ha clan.

JaHyun Kim Haboush was a Korean American scholar of Korean history and literature. Haboush was the King Sejong Professor of Korean Studies at Columbia University when she died in New York City in 2011.

Society in the Joseon dynasty was built upon Neo-Confucianist ideals, namely the three fundamental principles and five moral disciplines. There were four classes: the yangban nobility, the "middle class" jungin, sangmin, or the commoners, and the cheonmin, the outcasts at the very bottom. Society was ruled by the yangban, who constituted 10% of the population and had several privileges. Slaves were of the lowest standing.

Im Yunjidang was a Korean writer and neo-Confucian philosopher from the Joseon period. She defended the right for a woman to become a Confucian master and argued that men and women did not differ in their human nature by interpretations of Confucianism values in moral self-cultivation and human nature.

Naehun is a guidebook for women and the first known book written by a female author in Korea. It is one of the most representative books that reflects the social construction of gender and sexuality based on neo-Confucian ideals in premodern East Asia. It is also a unique historical source material, with various Korean royal court vocabulary describing appropriate behavior for a woman in accordance with neo-Confucian values.

Women in Korea during the Joseon period (1392–1897) had changing societal positions over time. They had fewer rights than women in the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392), and fewer rights than contemporary men. Their declining social position has been attributed to the adoption of Neo-Confucian principles. It was uncommon for women in Joseon to be able to read, and it was sometimes expected that women wear clothing that significantly covered their body and head when they were in public.