Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exercised freely. Such freedom implies the absence of interference from an overreaching state; its preservation may be sought through the constitution or other legal protection and security. It is in opposition to paid press, where communities, police organizations, and governments are paid for their copyrights.

Evin Prison is a prison located in the Evin neighborhood of Tehran, Iran. The prison has been the primary site for the housing of Iran's political prisoners since 1972, before and after the Iranian Revolution, in a purpose-built wing nicknamed "Evin University" due to the number of students and intellectuals housed there. Evin Prison has been accused of committing "serious human rights abuses" against its political dissidents and critics of the government.

Asr-e Azadegan was a Persian-language daily newspaper in Iran published briefly between 1999 and 2000.

The Reformists are a political faction in Iran. Iran's "reform era" is sometimes said to have lasted from 1997 to 2005—the length of President Mohammad Khatami's two terms in office. The Council for Coordinating the Reforms Front is the main umbrella organization and coalition within the movement; however, there are reformist groups not aligned with the council, such as the Reformists Front.

Abdollah Noori is an Iranian cleric and reformist politician. Despite his "long history of service to the Islamic Republic," he became the most senior Islamic politician to be sentenced to prison since the Iranian Revolution, when he was sentenced to five years in prison for political and religious dissent in 1999. He has been called the "bête noire" of Islamic conservatives in Iran.

Abdolkarim SoroushPersian pronunciation:[æbdolkæriːmsoruːʃ]), born Hossein Haj Faraj Dabbagh, is an Iranian Islamic thinker, reformer, Rumi scholar, public intellectual, and a former professor of philosophy at the University of Tehran and Imam Khomeini International University. He is among the most influential figures in the religious intellectual movement of Iran. Soroush is currently a visiting scholar at the University of Maryland in College Park, Maryland. He was also affiliated with other institutions, including Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Columbia, the Leiden-based International Institute as a visiting professor for the Study of Islam in the Modern World (ISIM) and the Wissenschaftskolleg in Berlin. He was named by Time magazine as one of the world's 100 most influential people in 2005, and by Prospect magazine as one of the most influential intellectuals in the world in 2008. Soroush's ideas, founded on relativism, prompted both supporters and critics to compare his role in reforming Islam to that of Martin Luther in reforming Christianity.

Masoud Behnoud is an Iranian journalist, He began his career as a journalist in 1964. Since then he has worked as an investigating journalist for different newspapers.

Seyyed Ebrahim Nabavi is an Iranian satirist, writer, diarist, and researcher. He currently writes in the news website Gooya and the online newspaper Rooz, and has a satirical program for the website and broadcasts on the Amsterdam based Radio Zamaneh.

Mohammad Ghouchani is an Iranian journalist. He has served as editor-in-chief of various reformist print media, many of which have been banned by the authorities.

Ansar-e Hezbollah is a conservative paramilitary organization in Iran. According to the Columbia World Dictionary of Islamism, it is a "semi-official quasi-clandestine organization of a paramilitary character that performs vigilante duties".

Maziar Bahari is an Iranian-Canadian journalist, filmmaker and human rights activist. He was a reporter for Newsweek from 1998 to 2011. Bahari was incarcerated by the Iranian government from June 21, 2009 to October 17, 2009, and has written a family memoir, Then They Came for Me, a New York Times best seller. His memoir is the basis for Jon Stewart's 2014 film Rosewater. Bahari later founded the IranWire citizen journalism news site, the freedom of expression campaign Journalism Is Not A Crime and the education and public art organization Paint the Change.

Hamid Mowlana is an Iranian-American author and academic. He is Professor Emeritus of International Relations in the School of International Services at American University in Washington, D.C. He was an advisor to the former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Iran is a constitutional, Islamic theocracy. Its official religion is the doctrine of the Twelver Jaafari School. Iran's law against blasphemy derives from Sharia. Blasphemers are usually charged with "spreading corruption on earth", or mofsed-e-filarz, which can also be applied to criminal or political crimes. The law against blasphemy complements laws against criticizing the Islamic regime, insulting Islam, and publishing materials that deviate from Islamic standards.

Religious intellectualism in Iran reached its apogee during the Persian Constitutional Revolution (1906–11). The process involved philosophers, sociologists, political scientists and cultural theorists.

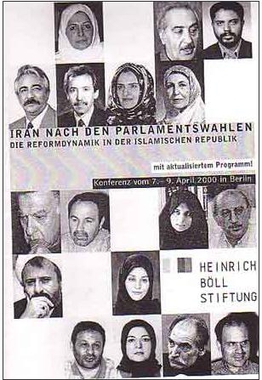

Iran After the Parliamentary Elections: The Dynamic of Reforms in the Islamic Republic was a three-day conference about future of Iran after landslide victory of the reformists in 2000 legislative election, organized by the Heinrich Böll Foundation and held in Berlin in April 2000. The conference was less notable for its proceedings than for its disruption by anti-regime Iranian exiles, and for the long prison sentences given to several participants upon their return to Iran.

Ahmad Bourghani Farahani was an Iranian reformist politician, journalist, writer and political analyst.

Iranian president Mohammad Khatami's two terms as president were criticized by conservatives, reformers, and opposition groups for various policies and viewpoints.

Steven Gan is a Malaysian journalist known for co-founding and editing the political news website Malaysiakini, Malaysia's "first and only" independent news source.

Neshat was a reformist and moderate Persian language newspaper published in Iran and headquartered in Tehran. The paper was founded in 1998 and published until 2005 when it was banned by the Iranian authorities.

Iran-e Farda is an Iranian nationalist-religious periodical publication printed in magazine-format and published digitally that focuses on current sociopolitical affairs of Iran.