Related Research Articles

Baker v. Vermont, 744 A.2d 864, was a lawsuit decided by Vermont Supreme Court on December 20, 1999. It was one of the first judicial affirmations of the right of same-sex couples to treatment equivalent to that afforded different-sex couples. The decision held that the state's prohibition on same-sex marriage denied rights granted by the Vermont Constitution. The court ordered the Vermont legislature to either allow same-sex marriages or implement an alternative legal mechanism according similar rights to same-sex couples.

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a landmark civil rights decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that laws banning interracial marriage violate the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The case involved Mildred Loving, a woman of color, and her white husband Richard Loving, who in 1958 were sentenced to a year in prison for marrying each other. Their marriage violated Virginia's Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which criminalized marriage between people classified as "white" and people classified as "colored". The Lovings appealed their conviction to the Supreme Court of Virginia, which upheld it. They then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which agreed to hear their case.

Goodridge v. Dept. of Public Health, 798 N.E.2d 941, is a landmark Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court case in which the Court held that the Massachusetts Constitution requires the state to legally recognize same-sex marriage. The November 18, 2003, decision was the first by a U.S. state's highest court to find that same-sex couples had the right to marry. Despite numerous attempts to delay the ruling, and to reverse it, the first marriage licenses were issued to same-sex couples on May 17, 2004, and the ruling has been in full effect since that date.

Many laws in the history of the United States have addressed marriage and the rights of married people. Common themes addressed by these laws include polygamy, interracial marriage, divorce, and same-sex marriage.

Same-sex marriage in Massachusetts has been legally recognized since May 17, 2004, as a result of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) ruling in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health that it was unconstitutional under the Massachusetts Constitution to allow only opposite-sex couples to marry. Massachusetts became the sixth jurisdiction in the world to legalize same-sex marriage. It was the first U.S. state to open marriage to same-sex couples.

Same-sex marriage in Vermont has been legal since September 1, 2009. Vermont was the first state to introduce civil unions on July 1, 2000, and the first state to introduce same-sex marriage by enacting a statute without being required to do so by a court decision. Same-sex marriage became legal earlier as the result of court decisions, not legislation, in four states: Massachusetts, California, Connecticut, and Iowa.

Same-sex marriage in New Jersey has been legally recognized since October 21, 2013, the effective date of a trial court ruling invalidating New Jersey's restriction of marriage to persons of different sexes. In September 2013, Mary C. Jacobson, Assignment Judge of the Mercer Vicinage of the Superior Court, ruled that as a result of the U.S. Supreme Court's June 2013 decision in United States v. Windsor, the Constitution of New Jersey requires the state to recognize same-sex marriages. The Windsor decision held that the federal government was required to provide the same benefits to same-sex couples who were married under state law as to other married couples. Therefore, the state court reasoned in Garden State Equality v. Dow that, because same-sex couples in New Jersey were limited to civil unions, which are not recognized as marriages under federal law, the state must permit civil marriage for same-sex couples. This ruling, in turn, relied on the 2006 decision of the New Jersey Supreme Court in Lewis v. Harris that the state was constitutionally required to afford the rights and benefits of marriage to same-sex couples. The Supreme Court had ordered the New Jersey Legislature to correct the constitutional violation, by permitting either same-sex marriage or civil unions with all the rights and benefits of marriage, within 180 days. In response, the Legislature passed a bill to legalize civil unions on December 21, 2006, which became effective on February 19, 2007.

Same-sex marriage in New Hampshire has been legal since January 1, 2010, based on legislation signed into law by Governor John Lynch on June 3, 2009. The law provided that civil unions, which the state had established on January 1, 2008, would be converted to marriages on January 1, 2011, unless dissolved, annulled, or converted to marriage before that date. New Hampshire became the fifth U.S. state to legalize same-sex marriage, and the fourth in New England.

Pace v. Alabama, 106 U.S. 583 (1883), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court affirmed that Alabama's anti-miscegenation statute was constitutional. This ruling was rejected by the Supreme Court in 1964 in McLaughlin v. Florida and in 1967 in Loving v. Virginia. Pace v. Alabama is one of the oldest court cases in America pertaining to interracial sex.

Kerrigan v. Commissioner of Public Health, 289 Conn. 135, 957 A.2d 407, is a 2008 decision by the Connecticut Supreme Court holding that allowing same-sex couples to form same-sex unions but not marriages violates the Connecticut Constitution. It was the third time that a ruling by the highest court of a U.S. state legalized same-sex marriage, following Massachusetts in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health (2003) and California in In re Marriage Cases (2008). The decision legalized same-sex marriage in Connecticut when it came into effect on November 12, 2008. There were no attempts made to amend the state constitution to overrule the decision, and gender-neutral marriage statutes were passed into law in 2009.

Same-sex marriage in Maine has been legally recognized since December 29, 2012. A bill for the legalization of same-sex marriages was approved by voters, 53–47 percent, on November 6, 2012, as Maine, Maryland and Washington became the first U.S. states to legalize same-sex marriage by popular vote. Election results were certified by the Maine Secretary of State's office and the Governor of Maine, Paul LePage, on November 29.

The Respect for Marriage Act is a landmark United States federal law passed by the 117th United States Congress and signed into law by President Joe Biden. It repeals the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), requires the U.S. federal government and all U.S. states and territories to recognize the validity of same-sex and interracial civil marriages in the United States, and protects religious liberty. Its first version in 2009 was supported by former Republican U.S. Representative Bob Barr, the original sponsor of DOMA, and former President Bill Clinton, who signed DOMA in 1996. Iterations of the proposal were put forth in the 111th, 112th, 113th, 114th, and 117th Congresses.

Mary L. Bonauto is an American lawyer and civil rights advocate who has worked to eradicate discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, and has been referred to by US Representative Barney Frank as "our Thurgood Marshall." She began working with the Massachusetts-based Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders, now named GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders (GLAD) organization in 1990. A resident of Portland, Maine, Bonauto was one of the leaders who both worked with the Maine legislature to pass a same-sex marriage law and to defend it at the ballot in a narrow loss during the 2009 election campaign. These efforts were successful when, in the 2012 election, Maine voters approved the measure, making it the first state to allow same-sex marriage licenses via ballot vote. Bonauto is best known for being lead counsel in the case Goodridge v. Department of Public Health which made Massachusetts the first state in which same-sex couples could marry in 2004. She is also responsible for leading the first strategic challenges to section three of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA).

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. state of Massachusetts enjoy the same rights as non-LGBT people. The U.S. state of Massachusetts is one of the most LGBT-friendly states in the country. In 2004, it became the first U.S. state to grant marriage licenses to same-sex couples after the decision in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health, and the sixth jurisdiction worldwide, after the Netherlands, Belgium, Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec.

The establishment of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in the U.S. state of Vermont is a recent occurrence, with most progress having taken place in the late 20th and the early 21st centuries. Vermont was one of 37 U.S. states, along with the District of Columbia, that issued marriage licenses to same-sex couples until the landmark Supreme Court ruling of Obergefell v. Hodges, establishing equal marriage rights for same-sex couples nationwide.

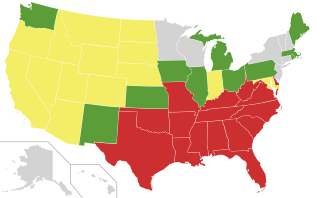

In the United States, anti-miscegenation laws were passed by most states to prohibit interracial marriage, and in some cases also prohibit interracial sexual relations. Some such laws predate the establishment of the United States, some dating to the later 17th or early 18th century, a century or more after the complete racialization of slavery. Nine states never enacted such laws; 25 states had repealed their laws by 1967, when the United States Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia that such laws were unconstitutional in the remaining 16 states. The term miscegenation was first used in 1863, during the American Civil War, by journalists to discredit the abolitionist movement by stirring up debate over the prospect of interracial marriage after the abolition of slavery.

This article contains a timeline of significant events regarding same-sex marriage in the United States. On June 26, 2015, the landmark US Supreme Court decision in Obergefell v. Hodges effectively ended restrictions on same-sex marriage in the United States.

Marc Solomon is a gay rights advocate. He was the national campaign director of Freedom to Marry, a group advocating same-sex marriage in the United States. Solomon is author of the book Winning Marriage: The Inside Story of How Same-Sex Couples Took on the Politicians and Pundits—and Won. As executive director of MassEquality from 2006 through 2009, he led the campaign to defeat a constitutional amendment that would have reversed Massachusetts' same-sex marriage court ruling. Politico describes Solomon as "warm and embracing" and "a born consensus builder—patient, adept at making personal connections, preternaturally gifted at politics without seeming at all like a politician."

In the United States, the history of same-sex marriage dates from the early 1940s, when the first lawsuits seeking legal recognition of same-sex relationships brought the question of civil marriage rights and benefits for same-sex couples to public attention though they proved unsuccessful. However marriage wasn't a request for the LGBTQ movement until the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in Washington (1987). The subject became increasingly prominent in U.S. politics following the 1993 Hawaii Supreme Court decision in Baehr v. Miike that suggested the possibility that the state's prohibition might be unconstitutional. That decision was met by actions at both the federal and state level to restrict marriage to male-female couples, notably the enactment at the federal level of the Defense of Marriage Act.

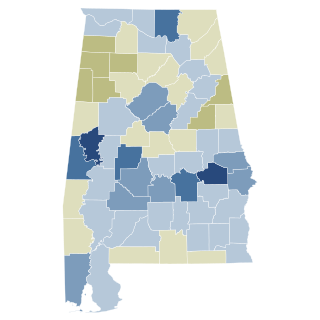

2000 Alabama Amendment 2, also known as the Alabama Interracial Marriage Amendment, was a proposed amendment to the Constitution of Alabama to remove Alabama's ban on interracial marriage. Interracial marriage had already been legalized nationwide 33 years prior in 1967, following Loving v. Virginia, making the vote symbolic. The amendment was approved with 59.5% voting yes, a 19 percentage point margin, though 25 of Alabama's 67 counties voted against it. Alabama was the last state to officially repeal its anti-miscegenation laws.

References

- 1 2 3 Greenberger, Scott S. (May 21, 2004). "History suggests race was the basis". The Boston Globe. Retrieved June 23, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Pascoe, Peggy (2009). What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America. Oxford University Press. pp. 40, 164ff., 194. ISBN 9780195094633.

- ↑ Greenberger, Scott S. (May 21, 2004). "History Suggests Race was the Basis". The Boston Globe .

- ↑ Saltzman, Jonathan (October 7, 2005). "SJC Hears Challenge to Marriage Law". The Boston Globe .

- ↑ GLAD: Cote-Whitacre v. Department of Public Health, Complaint Archived August 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine , accessed July 5, 2013

- ↑ Gilmore, Al-Tony (January 1973). "Jack Johnson and White Women: The National Impact". Journal of Negro History. 58 (1): 32. doi:10.2307/2717154. JSTOR 2717154. S2CID 149937203.

- 1 2 Wallenstein, Peter (2002). Tell the Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage, and Law–An American History . Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 134, 136. ISBN 9780312294748.

- ↑ Hagedorn, Ann (2007). Savage Peace: Hope and Fear in America, 1919 . NY: Simon & Schuster. p. 288. ISBN 9781416539711.

- 1 2 Belluck, Pam (May 21, 2004). "Governor Seeks to Invalidate Some Same-Sex Marriages". New York Times. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ↑ Belluck, Pam (April 25, 2004). "Romney Won't Let Gay Outsiders Wed In Massachusetts". New York Times. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Defiance, rebuke on gay marriage". Boston Globe. May 12, 2004. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ↑ "Gays Battle 1913 Massachusetts Law". CBS News. July 13, 2004.

- ↑ Belluck, Pam (June 18, 2004). "Eight Diverse Gay Couples Join to Fight Massachusetts". New York Times. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ↑ Greenberger, Scott S. (July 13, 2004). "Reilly says curb on gay marriage blunts backlash". Boston Globe. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ↑ "Gay couples barred from marrying in Massachusetts will appeal ruling". The Advocate. August 21, 2004. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ↑ Cote-Whitacre v. Department of Public Health, 844 N.E.2d 623 (Mass. 2006)

- 1 2 Belluck, Pam (March 30, 2006). "Massachusetts Court Limits Same-Sex Marriages". New York Times. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ↑ Connolly, Thomas E. (September 29, 2006). "Sandra Cote-Whitacre & others vs. Department of Public Health & others Memorandum of Decision on Whether Same-Sex Marriage is Prohibited in New York and Rhode Island" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 30, 2006. Retrieved July 7, 2013. Page 8.

- ↑ Lewis, Raphael (April 22, 2004). "Law curbing out-of-state couples faces a challenge". Boston Globe. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ↑ Abraham, Yvonne; Greenberger, Scott S. (May 6, 2004). "Senators would let gay outsiders wed". Boston Globe. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- 1 2 Lewis, Raphael (May 20, 2004). / "Senate Votes to End 1913 Law". Boston Globe. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ Peters, Jeremy W. (May 29, 2008). "New York to Back Same-Sex Unions From Elsewhere". New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ↑ Egelko, Bob (May 16, 2008). "State's top court strikes down marriage ban". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- ↑ McKinley, Jesse (June 18, 2008). "Hundreds of Same-Sex Couples Wed in California". New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ↑ Michaels, Spencer (June 17, 2008). "Same-Sex Couples Begin Marrying in California". NPR. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ↑ Viser, Matt (July 10, 2008). "Gay-marriage advocates hope to repeal old law". Boston Globe. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ↑ Moskowitz, Eric (July 16, 2008). "Senate votes to repeal 1913 law". Boston Globe. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ↑ Moskowitz, Eric (July 30, 2008). "A curb on gay marriage will fall". Boston Globe. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ↑ Levenson, Michael (August 1, 2008). "Same-sex couples applaud repeal". Boston Globe. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ↑ Lefferts, Jennifer Fenn (November 1, 2007). "Parents, others protest 'Laramie' at high school". Boston Globe. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- ↑ Jacobs, Ethan (October 30, 2008). "1913 law petition fails". Bay Windows. Retrieved July 6, 2013.