The Christian Institute (CI) is a charity operating in the United Kingdom, promoting a Christian viewpoint, founded on a belief in Biblical inerrancy. The CI is a registered charity. The group does not report numbers of staff, volunteers or members with only the Director, Colin Hart, listed as a representative. However, according to the accounts and trustees annual report for the financial year ending 2017, the average head count of employees during the year was 48 (2016:46).

The right to freedom of religion in the United Kingdom is provided for in all three constituent legal systems, by devolved, national, European, and international law and treaty. Four constituent nations compose the United Kingdom, resulting in an inconsistent religious character, and there is no state church for the whole kingdom.

Freedom of religion in Canada is a constitutionally protected right, allowing believers the freedom to assemble and worship without limitation or interference.

The rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland have varied over time.

Christopher Stephen Myles Kempling is a Canadian educator who was suspended by the British Columbia College of Teachers and disciplined by the Quesnel School District for anti-gay comments in letters to the editor of the Quesnel Cariboo Observer. Kempling challenged the suspension in court, arguing that his right to freedom of expression had been violated. The British Columbia Court of Appeal ruled against him, ruling that limitations on his freedom of expression were justified by the school's duty to maintain a tolerant and discrimination-free environment. Kempling filed a complaint with the British Columbia Human Rights Tribunal alleging that the disciplinary action taken against him by the school district infringed his freedom of religion; this complaint was dismissed on similar grounds.

United Kingdom employment equality law is a body of law which legislates against prejudice-based actions in the workplace. As an integral part of UK labour law it is unlawful to discriminate against a person because they have one of the "protected characteristics", which are, age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, race, religion or belief, sex, pregnancy and maternity, and sexual orientation. The primary legislation is the Equality Act 2010, which outlaws discrimination in access to education, public services, private goods and services, transport or premises in addition to employment. This follows three major European Union Directives, and is supplement by other Acts like the Protection from Harassment Act 1997. Furthermore, discrimination on the grounds of work status, as a part-time worker, fixed term employee, agency worker or union membership is banned as a result of a combination of statutory instruments and the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992, again following European law. Disputes are typically resolved in the workplace in consultation with an employer or trade union, or with advice from a solicitor, ACAS or the Citizens Advice Bureau a claim may be brought in an employment tribunal. The Equality Act 2006 established the Equality and Human Rights Commission, a body designed to strengthen enforcement of equality laws.

Eweida v United Kingdom[2013] ECHR 37 is a UK labour law decision of the European Court of Human Rights, concerning the duty of the government of the United Kingdom to protect the religious rights of individuals under the European Convention on Human Rights. The European Court found that the British government had failed to protect the complainant's right to manifest her religion, in breach of Article 9 of the European Convention. For failing to protect her rights, the British government was found liable to pay non-pecuniary damages of €2,000, along with a costs award of €30,000.

McClintock v Department of Constitutional Affairs [2008] IRLR 29, Times 5 December 2007, is a UK employment discrimination law case concerning freedom of religion under Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights, unfair dismissal and the new Employment Equality Regulations 2003.

Redfearn v Serco Ltd [2006] EWCA Civ 659 and Redfearn v United Kingdom [2012] ECHR 1878 is a UK labour law and European Court of Human Rights case. It held that UK law was deficient in not allowing a potential claim based on discrimination for one's political belief. Before the case was decided, the Equality Act 2010 provided a remedy to protect political beliefs, though it had not come into effect when this case was brought forth.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. state of Louisiana may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Louisiana, and same-sex marriage has been recognized in the state since June 2015 as a result of the Supreme Court's decision in Obergefell v. Hodges.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. state of Maine enjoy the same rights as non-LGBT people, including the ability to marry and adopt. Same-sex marriage has been recognized in Maine since December 2012, following a referendum in which a majority of voters approved an initiative to legalize same-sex marriage. Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity is prohibited in the areas of employment, housing, credit and public accommodations. In addition, the use of conversion therapy on minors has been outlawed since 2019.

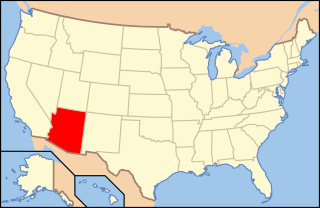

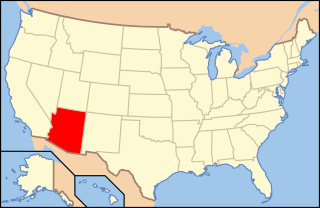

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the U.S. state of Arizona may face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Arizona, and same-sex couples are able to marry and adopt. Nevertheless, the state provides only limited protections against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. Several cities, including Phoenix and Tucson, have enacted ordinances to protect LGBT people from unfair discrimination in employment, housing and public accommodations.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. commonwealth of Kentucky still face some legal challenges not experienced by other people. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Kentucky. Same-sex couples and families headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for all of the protections available to opposite-sex married couples. On February 12, 2014, a federal judge ruled that the state must recognize same-sex marriages from other jurisdictions, but the ruling was put on hold pending review by the Sixth Circuit. Same sex-marriage is now legal in the state under the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges. The decision, which struck down Kentucky's statutory and constitutional bans on same-sex marriages, and all other same sex marriage bans elsewhere in the country, was handed down on June 26, 2015.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Kansas may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Kansas, and the state has prohibited discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in employment, housing and public accommodations since 2020.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. state of Alaska may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT Alaskans. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 1980, and same-sex couples have been able to marry since October 2014. The state offers few legal protections against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, leaving LGBT people vulnerable to discrimination in housing and public accommodations; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBT people is illegal under federal law. In addition, four Alaskan cities, Anchorage, Juneau, Sitka and Ketchikan, representing about 46% of the state population, have passed discrimination protections for housing and public accommodations.

Ladele v London Borough of Islington [2009] EWCA Civ 1357 is a UK labour law case concerning discrimination against same sex couples by a religious person in a public office.

Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, 584 U.S. ___ (2018), was a case in the Supreme Court of the United States that dealt with whether owners of public accommodations can refuse certain services based on the First Amendment claims of free speech and free exercise of religion, and therefore be granted an exemption from laws ensuring non-discrimination in public accommodations—in particular, by refusing to provide creative services, such as making a custom wedding cake for the marriage of a gay couple, on the basis of the owner's religious beliefs.

Bull and another v Hall and another[2013] UKSC 73 was a Supreme Court of the United Kingdom discrimination case between Peter and Hazelmary Bull and Martin Hall and Steven Preddy. Hall and Preddy, a homosexual couple, brought the case after the Bulls refused to give them a double room in their guesthouse, citing their religious beliefs. Following appeals, the Supreme Court held the rulings of the lower courts in deciding for Hall and Preddy and against the Bulls. The court said that Preddy and Hall faced discrimination which could not be justified by the Bulls' right to religious belief. It was held that people in the United Kingdom could not justify discrimination against others on the basis of their sexual orientation due to their religious beliefs.

Forstater v Center for Global Development Europe is a UK employment and discrimination case brought by Maya Forstater against the Center for Global Development (CGD). The Employment Appeal Tribunal decided that gender-critical views are capable of being protected as a belief under the Equality Act 2010. The tribunal further clarified that this finding does not mean that people with gender-critical beliefs can express them in a manner that discriminates against trans people.

Jeremy Charles Baring Pemberton is a British Anglican priest who was the first priest in the Church of England to enter into a same-sex marriage when he married another man in 2014. As same-sex marriages are not accepted by the church, he was denied a job as a chaplain for the National Health Service by John Sentamu, the Archbishop of York. Before then, he had been an Anglican priest for 33 years.