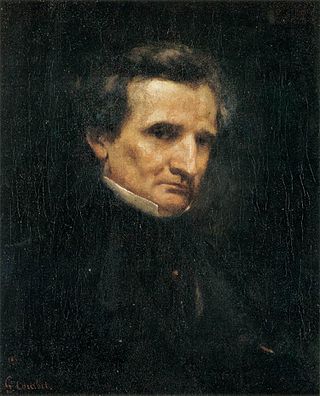

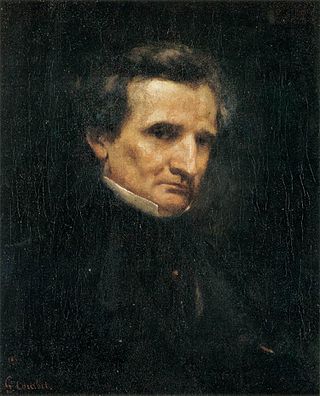

Louis-Hector Berlioz was a French Romantic composer and conductor. His output includes orchestral works such as the Symphonie fantastique and Harold in Italy, choral pieces including the Requiem and L'Enfance du Christ, his three operas Benvenuto Cellini, Les Troyens and Béatrice et Bénédict, and works of hybrid genres such as the "dramatic symphony" Roméo et Juliette and the "dramatic legend" La Damnation de Faust.

Roméo et Juliette is a seven-movement symphonie dramatique for orchestra and three choruses, with vocal solos, by French composer Hector Berlioz. Émile Deschamps wrote its libretto with Shakespeare's play as his base. The work was completed in 1839 and first performed on 24 November of that year, but it was modified before its first publication, in 1847, and modified again for the 2ème Édition of 1857, today's reference. It bears the catalogue numbers Op. 17 and H. 79. Regarded as one of Berlioz's finest achievements, Roméo et Juliette is also among his most original in form and his most comprehensive and detailed to follow a program. The vocal forces are used in the 1st, 5th and 7th movements.

Orfeo ed Euridice is an opera composed by Christoph Willibald Gluck, based on the myth of Orpheus and set to a libretto by Ranieri de' Calzabigi. It belongs to the genre of the azione teatrale, meaning an opera on a mythological subject with choruses and dancing. The piece was first performed at the Burgtheater in Vienna on 5 October 1762, in the presence of Empress Maria Theresa. Orfeo ed Euridice is the first of Gluck's "reform" operas, in which he attempted to replace the abstruse plots and overly complex music of opera seria with a "noble simplicity" in both the music and the drama.

La damnation de Faust, Op. 24 is a work for four solo voices, full seven-part chorus, large children's chorus and orchestra by the French composer Hector Berlioz. He called it a "légende dramatique". It was first performed at the Opéra-Comique in Paris on 6 December 1846.

Benvenuto Cellini is an opera semiseria in four tableaux by Hector Berlioz, his first full-length work for the stage. Premiered at the Académie Royale de Musique on 10 September 1838, it is a setting of a libretto by Léon de Wailly and Henri Auguste Barbier, who invented most of the plot inspired by the memoirs of the Florentine sculptor Benvenuto Cellini. The opera is technically challenging and was until the 21st century rarely performed. But its overture sometimes features in orchestral concerts, as does the concert overture Le carnaval romain which Berlioz composed from material in the opera.

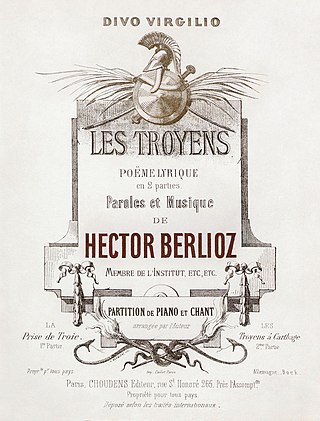

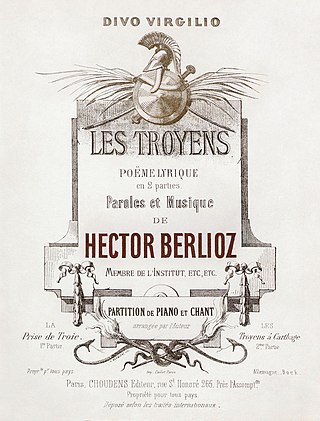

Les Troyens is a French grand opera in five acts, running for about five hours, by Hector Berlioz. The libretto was written by Berlioz himself from Virgil's epic poem the Aeneid; the score was composed between 1856 and 1858. Les Troyens is Berlioz's most ambitious work, the summation of his entire artistic career, but he did not live to see it performed in its entirety. Under the title Les Troyens à Carthage, the last three acts were premièred with many cuts by Léon Carvalho's company, the Théâtre Lyrique, at their theatre on the Place du Châtelet in Paris on 4 November 1863, with 21 repeat performances. The reduced versions run for about three hours. After decades of neglect, today the opera is considered by some music critics as one of the finest ever written.

Lélio, ou Le retour à la vie, Op. 14b, is a work incorporating music and spoken text by the French composer Hector Berlioz, intended as a sequel to his Symphonie fantastique. It is written for a narrator, solo tenor and baritone, mixed chorus, and an orchestra including piano.

"O Salutaris Hostia" is a section of one of the Eucharistic hymns written by Thomas Aquinas for the Feast of Corpus Christi. He wrote it for the Hour of Lauds in the Divine Office. It is actually the last two stanzas of the hymn Verbum supernum prodiens, and is used for the Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament. The other two hymns written by Aquinas for the Feast contain the famous sections Panis angelicus and Tantum ergo.

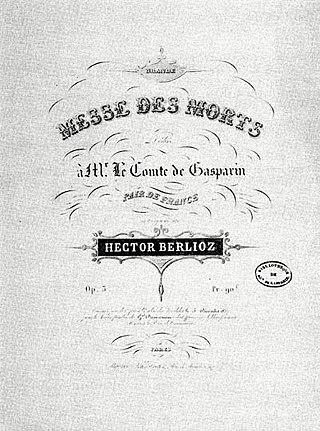

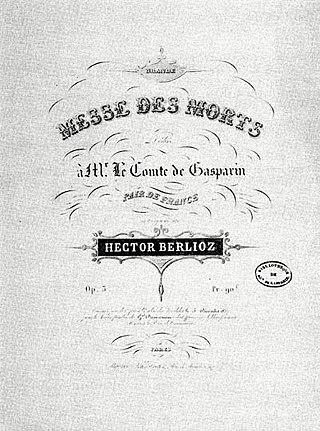

The Grande Messe des morts, Op. 5, by Hector Berlioz was composed in 1837. The Grande Messe des Morts is one of Berlioz's best-known works, with a tremendous orchestration of woodwind and brass instruments, including four antiphonal offstage brass ensembles. The work derives its text from the traditional Latin Requiem Mass. It has a duration of approximately ninety minutes, although there are faster recordings of under seventy-five minutes.

Gioachino Rossini's Petite messe solennelle was written in 1863, possibly at the request of Count Alexis Pillet-Will for his wife Louise, to whom it is dedicated. The composer, who had retired from composing operas more than 30 years before, described it as "the last of my péchés de vieillesse".

Les nuits d'été, Op. 7, is a song cycle by the French composer Hector Berlioz. It is a setting of six poems by Théophile Gautier. The cycle, completed in 1841, was originally for soloist and piano accompaniment. Berlioz orchestrated one of the songs in 1843, and did the same for the other five in 1856. The cycle was neglected for many years, but during the 20th century it became, and has remained, one of the composer's most popular works. The full orchestral version is more frequently performed in concert and on record than the piano original. The theme of the work is the progress of love, from youthful innocence to loss and finally renewal.

Jean-Paul Penin is a French conductor.

L'enfance du Christ, Opus 25, is an oratorio by the French composer Hector Berlioz, based on the Holy Family's flight into Egypt. Berlioz wrote his own words for the piece. Most of it was composed in 1853 and 1854, but it also incorporates an earlier work La fuite en Egypte (1850). It was first performed at the Salle Herz in Paris on 10 December 1854, with Berlioz conducting and soloists from the Opéra-Comique: Jourdan (Récitant), Depassio (Hérode), the couple Meillet and Bataille.

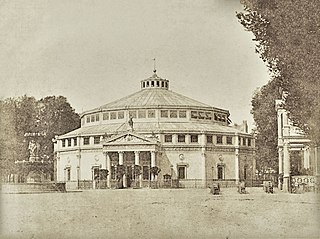

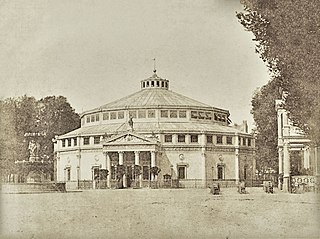

The Cirque d'Été, a former Parisian equestrian theatre, was built in 1841 to designs by the architect Jacques Hittorff. It was used as the summer home of the Théâtre Franconi, the equestrian troupe of the Cirque Olympique, the license for which had been sold in 1836 to Louis Dejean by Adolphe Franconi, the grandson of its founder, Antonio Franconi. The cirque was later also used for other purposes, including grand concerts conducted by Hector Berlioz.

Alexis Dupont was a French operatic tenor who sang at the Opéra-Comique from 1821 to 1823 and the Paris Opera from 1826 to 1841. There he created a number of roles in operas by Rossini, Auber, Halévy and Meyerbeer. He had a significant association with Berlioz, creating the tenor solo in Roméo et Juliette in 1839; and he sang in the Mozart Requiem at Chopin's funeral in 1849.

St. Cecilia Mass is the common name of a solemn mass in G major by Charles Gounod, composed in 1855 and scored for three soloists, mixed choir, orchestra and organ. The official name is Messe solennelle en l’honneur de Sainte-Cécile, in homage of St. Cecilia, the patron saint of music. The work was assigned CG 56 in the catalogue of the composer's works.

Henri Valentino was a French conductor and violinist. From 1824 to 1832, he was co-conductor of the Paris Opera, where he prepared and conducted the premieres of the first two grand operas, Auber's La muette de Portici and Rossini's Guillaume Tell. From 1832 to 1836, he was First Conductor of the Opéra-Comique, and from 1837 to 1841, conductor of classical music at the Concerts Valentino in a hall on the rue Saint-Honoré in Paris.

Michael Spyres is an American operatic baritenor. He is particularly associated with the bel canto repertoire, especially the works of Rossini, and heroic roles in French grand opera.

Messe de minuit pour Noël, H.9, is a mass for four voices and orchestra by Marc-Antoine Charpentier, written in 1694 based on the melodies of ten French Christmas carols. Charpentier called for eight soloists, a duo of two sopranos and two trios of alto, tenor and bass, but it can be performed by five soloists. Choir and orchestra are in four parts, scored for flutes, strings, organ and basso continuo. The mass is regarded as unique in both the composer's work and in the genre. While in Charpentier's time, the mass was performed by all-male choirs, it has later been performed and recorded also by mixed choirs with modern instruments.