Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's brother Charles Wesley were also significant early leaders in the movement. They were named Methodists for "the methodical way in which they carried out their Christian faith". Methodism originated as a revival movement in the Church of England in the 18th century and became a separate denomination after Wesley's death. The movement spread throughout the British Empire, the United States, and beyond because of vigorous missionary work, and today has about 80 million adherents worldwide.

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th century in the United States. The Second Great Awakening, which spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching, sparked a number of reform movements. Revivals were a key part of the movement and attracted hundreds of converts to new Protestant denominations. The Methodist Church used circuit riders to reach people in frontier locations.

The Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) was the oldest and largest Methodist denomination in the United States from its founding in 1784 until 1939. It was also the first religious denomination in the US to organize itself nationally. In 1939, the MEC reunited with two breakaway Methodist denominations to form the Methodist Church. In 1968, the Methodist Church merged with the Evangelical United Brethren Church to form the United Methodist Church.

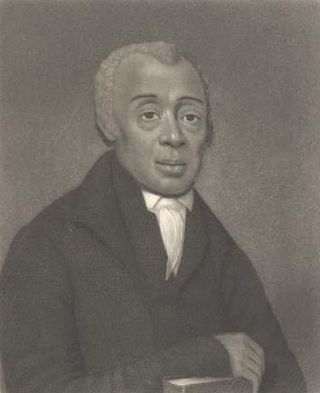

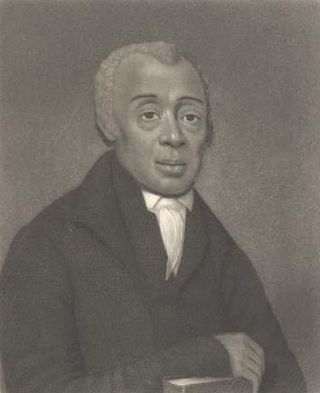

Richard Allen was a minister, educator, writer, and one of the United States' most active and influential black leaders. In 1794, he founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), the first independent Black denomination in the United States. He opened his first AME church in 1794 in Philadelphia.

The Evangelical United Brethren Church (EUB) was a North American Protestant denomination from 1946 to 1968 with Arminian theology, roots in the Mennonite and German Reformed, and communities, and close ties to Methodism. It was formed by the merger of the Evangelical Church and the Church of the United Brethren in Christ. The United Brethren and the Evangelical Association had considered merging off and on since the early 19th century because of their common emphasis on holiness and evangelism and their common German heritage. In 1968, the United States section of the EUB merged with the Methodist Church to form the United Methodist Church, while the Canadian section joined the United Church of Canada.

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a Methodist Black church. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexional polity. The African Methodist Episcopal Church is the first independent Protestant denomination to be founded by black people; though it welcomes and has members of all ethnicities.

The Christian Methodist Episcopal (C.M.E.) Church is a historically black denomination within the broader context of Wesleyan Methodism founded and organized by John Wesley in England in 1744 and established in America as the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1784. It is considered to be a mainline denomination. The CME Church was organized on December 16, 1870 in Jackson, Tennessee by 41 former slave members with the full support of their white sponsors in their former Methodist Episcopal Church, South who met to form an organization that would allow them to establish and maintain their own polity. They ordained their own bishops and ministers without their being officially endorsed or appointed by the white-dominated body. They called this fellowship the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church in America, which it remained until their successors adopted the current name in 1954. The Christian Methodist Episcopal today has a church membership of people from all racial backgrounds. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology.

The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, or the AME Zion Church (AMEZ) is a historically African-American Christian denomination based in the United States. It was officially formed in 1821 in New York City, but operated for a number of years before then. The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology.

The black church is the faith and body of Christian denominations and congregations in the United States that minister predominantly to African Americans, as well as their collective traditions and members. The term "black church" can also refer to individual congregations.

The Free Methodist Church is a denomination of Methodism, which is a branch of Protestantism. It was founded in 1860 in New York by a group, led by B. T. Roberts, who was defrocked in the Methodist Episcopal Church for criticisms of the spiritual laxness of the church hierarchy. The Free Methodists are so named because they believed it was improper to charge for better seats in pews closer to the pulpit. They also opposed slavery and supported freedom for all slaves in the United States, while many Methodists in the South at that time did not actively oppose slavery. Beyond that, they advocated "freedom" from secret societies, which had allegedly undermined parts of the Methodist Episcopal Church.

Arthur James Moore was an American bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (MECS), the Methodist Church, and the United Methodist Church, elected in 1930.

James Osgood Andrew was elected in 1832 an American bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church. After the split within the church in 1844, he continued as a bishop in the Methodist Episcopal Church, South.

Daniel Alexander Payne was an American bishop, educator, college administrator and author. A major shaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), Payne stressed education and preparation of ministers and introduced more order in the church, becoming its sixth bishop and serving for more than four decades (1852–1893) as well as becoming one of the founders of Wilberforce University in Ohio in 1856. In 1863, the AME Church bought the college and chose Payne to lead it; he became the first African-American president of a college in the United States and served in that position until 1877.

An episcopal area in the United Methodist Church (UMC) is a basic unit of this denomination. It is a region presided over by a resident bishop that is similar to a diocese in other Christian denominations. Each annual conference in the UMC is within a single episcopal area; some episcopal areas include more than one annual conference. Episcopal areas are found in the United States as well as internationally. In some cases, such as the Western Jurisdiction of the US as well as some places internationally, an episcopal area covers a very large territory.

Religion of black Americans refers to the religious and spiritual practices of African Americans. Historians generally agree that the religious life of black Americans "forms the foundation of their community life". Before 1775 there was scattered evidence of organized religion among black people in the Thirteen Colonies. The Methodist and Baptist churches became much more active in the 1780s. Their growth was quite rapid for the next 150 years, until their membership included the majority of black Americans.

Methodist views on the ordination of women in the rite of holy orders are diverse.

Henry McNeal Turner was an American minister, politician, and the 12th elected and consecrated bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). After the American Civil War, he worked to establish new A.M.E. congregations among African Americans in Georgia. Born free in South Carolina, Turner had learned to read and write and became a Methodist preacher. He joined the AME Church in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1858, where he became a minister. Founded by free blacks in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the early 19th century, the A.M.E. Church was the first independent black denomination in the United States. Later Turner had pastorates in Baltimore, Maryland, and Washington, DC.

The history of Methodism in the United States dates back to the mid-18th century with the ministries of early Methodist preachers such as Laurence Coughlan and Robert Strawbridge. Following the American Revolution most of the Anglican clergy who had been in America came back to England. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, sent Thomas Coke to America where he and Francis Asbury founded the Methodist Episcopal Church, which was to later establish itself as the largest denomination in America during the 19th century.

The Bible Methodist Connection of Churches is a Methodist denomination within the conservative holiness movement.

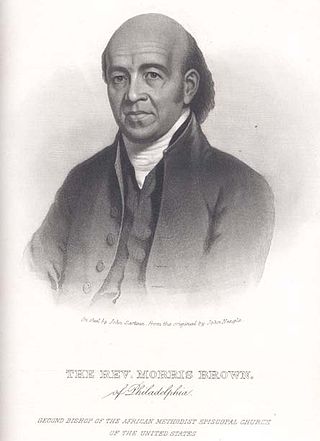

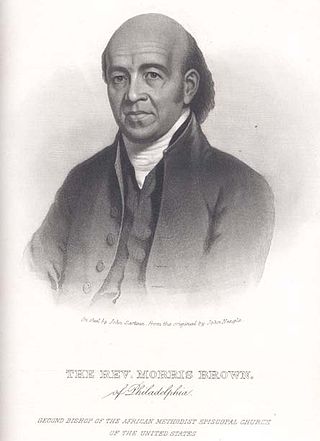

Morris Brown was one of the founders of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and its second presiding bishop. He founded Emanuel AME Church in his native Charleston, South Carolina. It was implicated in the slave uprising planned by Denmark Vesey, also of this church, and after that was suppressed, Brown was imprisoned for nearly a year. He was never convicted of a crime.