Related Research Articles

Absolute zero is the lowest limit of the thermodynamic temperature scale, a state at which the enthalpy and entropy of a cooled ideal gas reach their minimum value, taken as zero kelvin. The fundamental particles of nature have minimum vibrational motion, retaining only quantum mechanical, zero-point energy-induced particle motion. The theoretical temperature is determined by extrapolating the ideal gas law; by international agreement, absolute zero is taken as −273.15 degrees on the Celsius scale, which equals −459.67 degrees on the Fahrenheit scale. The corresponding Kelvin and Rankine temperature scales set their zero points at absolute zero by definition.

The British thermal unit is a unit of heat; it is defined as the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of one pound of water by one degree Fahrenheit. It is also part of the United States customary units. Heat is now known to be equivalent to energy. The modern SI unit for heat and energy is the joule (J); one BTU equals about 1,055 J.

The Fahrenheit scale is a temperature scale based on one proposed in 1724 by the physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1686–1736). It uses the degree Fahrenheit as the unit. Several accounts of how he originally defined his scale exist, but the original paper suggests the lower defining point, 0 °F, was established as the freezing temperature of a solution of brine made from a mixture of water, ice, and ammonium chloride. The other limit established was his best estimate of the average human body temperature, originally set at 90 °F, then 96 °F. However, he noted a middle point of 32 °F, to be set to the temperature of ice water.

The Rankine scale is an absolute scale of thermodynamic temperature named after the Glasgow University engineer and physicist Macquorn Rankine, who proposed it in 1859. Just like the Kelvin scale, which was first proposed in 1848, zero on the Rankine scales is absolute zero, but a temperature difference of one Rankine degree is defined as equal to one Fahrenheit degree, rather than the Celsius degree used on the kelvin scale. Thus, a temperature of 0 K is equal to 0 °R, and a temperature of −459.67 °F is equal to 0 °R.

Standard temperature and pressure (STP) are standard sets of conditions for experimental measurements to be established to allow comparisons to be made between different sets of data. The most used standards are those of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), although these are not universally accepted standards. Other organizations have established a variety of alternative definitions for their standard reference conditions.

A thermocouple is an electrical device consisting of two dissimilar electrical conductors forming an electrical junction. A thermocouple produces a temperature-dependent voltage as a result of the Seebeck effect, and this voltage can be interpreted to measure temperature. Thermocouples are widely used as temperature sensors.

Thermodynamic temperature is a quantity defined in thermodynamics as distinct from kinetic theory or statistical mechanics. A thermodynamic temperature reading of zero is of particular importance for the third law of thermodynamics. By courtesy, it reported on the Kelvin scale of temperature in which the unit of measure is the kelvin. For comparison, a temperature of 295 K is equal to 21.85 °C and 71.33 °F.

Steelmaking is the process of producing steel from iron ore and/or scrap. In steelmaking, impurities such as nitrogen, silicon, phosphorus, sulfur and excess carbon are removed from the sourced iron, and alloying elements such as manganese, nickel, chromium, carbon and vanadium are added to produce different grades of steel. Limiting dissolved gases such as nitrogen and oxygen and entrained impurities in the steel is also important to ensure the quality of the products cast from the liquid steel.

Fused quartz,fused silica or quartz glass is a glass consisting of almost pure silica (silicon dioxide, SiO2) in amorphous (non-crystalline) form. This differs from all other commercial glasses in which other ingredients are added which change the glasses' optical and physical properties, such as lowering the melt temperature. Fused quartz, therefore, has high working and melting temperatures, making it less desirable for most common applications.

Stephanie Louise Kwolek was an American chemist who is known for inventing Kevlar. Her career at the DuPont company spanned more than 40 years. She discovered the first of a family of synthetic fibers of exceptional strength and stiffness: poly-paraphenylene terephthalamide.

A refractory material or refractory is a material that is resistant to decomposition by heat, pressure, or chemical attack, and retains strength and form at high temperatures. Refractories are polycrystalline, polyphase, inorganic, non-metallic, porous, and heterogeneous. They are typically composed of oxides or carbides, nitrides etc. of the following materials: silicon, aluminium, magnesium, calcium, and zirconium. Some metals with melting points >1850 °C like niobium, chromium, zirconium, tungsten, rhenium, tantalum, molybdenum etc. are also considered refractories.

The term degree is used in several scales of temperature. The symbol ° is usually used, followed by the initial letter of the unit, for example “°C” for degree(s) Celsius. A degree can be defined as a set change in temperature measured against a given scale, for example, one degree Celsius is one hundredth of the temperature change between the point at which water starts to change state from solid to liquid state and the point at which it starts to change from its liquid to gaseous state.

Cryochemistry is the study of chemical interactions at temperatures below −150 °C. It is derived from the Greek word cryos, meaning 'cold'. It overlaps with many other sciences, including chemistry, cryobiology, condensed matter physics, and even astrochemistry.

A combustible material is something that can burn in air. A combustible material is flammable if it ignites easily at ambient temperatures. In other words, a combustible material ignites with some effort and a flammable material catches fire immediately on exposure to flame.

Loss on ignition (LOI) is a test used in inorganic analytical chemistry and soil science, particularly in the analysis of minerals and the chemical makeup of soil. It consists of strongly heating ("igniting") a sample of the material at a specified temperature, allowing volatile substances to escape, until its mass ceases to change. This may be done in air, or in some other reactive or inert atmosphere. The simple test typically consists of placing a few grams of the material in a tared, pre-ignited crucible and determining its mass, placing it in a temperature-controlled furnace for a set time, cooling it in a controlled (e.g. water-free, CO2-free) atmosphere, and redetermining the mass. The process may be repeated to show that mass-change is complete. A variant of the test in which mass-change is continually monitored as the temperature is changed, is thermogravimetry.

Wuchang is a county-level city of Heilongjiang Province, Northeast China, it is under the administration of the prefecture-level city of Harbin, it borders Acheng District to the north, Shangzhi to the northeast, Shuangcheng District to the northwest, and Jilin Province to the south and the west.

The degree Celsius is a unit of temperature on the Celsius scale, a temperature scale originally known as the centigrade scale. The degree Celsius can refer to a specific temperature on the Celsius scale or a unit to indicate a difference or range between two temperatures. It is named after the Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius (1701–1744), who developed a similar temperature scale. Before being renamed to honor Anders Celsius in 1948, the unit was called centigrade, from the Latin centum, which means 100, and gradus, which means steps.

Temperature is a physical quantity that expresses hot and cold. It is the manifestation of thermal energy, present in all matter, which is the source of the occurrence of heat, a flow of energy, when a body is in contact with another that is colder or hotter.

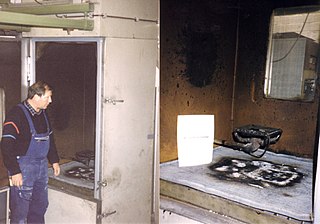

An industrial furnace, also known as a direct heater or a direct fired heater, is a device used to provide heat for an industrial process, typically higher than 400 degrees Celsius. They are used to provide heat for a process or can serve as reactor which provides heats of reaction. Furnace designs vary as to its function, heating duty, type of fuel and method of introducing combustion air. Heat is generated by an industrial furnace by mixing fuel with air or oxygen, or from electrical energy. The residual heat will exit the furnace as flue gas. These are designed as per international codes and standards the most common of which are ISO 13705 / American Petroleum Institute (API) Standard 560. Types of industrial furnaces include batch ovens, vacuum furnaces, and solar furnaces. Industrial furnaces are used in applications such as chemical reactions, cremation, oil refining, and glasswork.

Steam cracking is a petrochemical process in which saturated hydrocarbons are broken down into smaller, often unsaturated, hydrocarbons. It is the principal industrial method for producing the lighter alkenes, including ethene and propene. Steam cracker units are facilities in which a feedstock such as naphtha, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), ethane, propane or butane is thermally cracked through the use of steam in steam cracking furnaces to produce lighter hydrocarbons. The propane dehydrogenation process may be accomplished through different commercial technologies. The main differences between each of them concerns the catalyst employed, design of the reactor and strategies to achieve higher conversion rates.

References

- ↑ "M. W. Kellogg's new pyrolysis furnace...", Technical Survey, 1975, accessed on Google Books 2014-07-31

- ↑ "the new Kellogg-Idemistu Millisecond Furnace", High Temperature Chemical Reaction Engineering, Symposium Series No. 43, Institution of Chemical Engineers, 1975, p.12-1, accessed on Google Books 2014-07-31