Related Research Articles

Mining is the extraction of valuable geological materials and minerals from the surface of the Earth. Mining is required to obtain most materials that cannot be grown through agricultural processes, or feasibly created artificially in a laboratory or factory. Ores recovered by mining include metals, coal, oil shale, gemstones, limestone, chalk, dimension stone, rock salt, potash, gravel, and clay. The ore must be a rock or mineral that contains valuable constituent, can be extracted or mined and sold for profit. Mining in a wider sense includes extraction of any non-renewable resource such as petroleum, natural gas, or even water.

The economy of Namibia has a modern market sector, which produces most of the country's wealth, and a traditional subsistence sector. Although the majority of the population engages in subsistence agriculture and herding, Namibia has more than 200,000 skilled workers and a considerable number of well-trained professionals and managerials.

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest, and cultural value. On Earth, it includes sunlight, atmosphere, water, land, all minerals along with all vegetation, and wildlife.

Energy economics is a broad scientific subject area which includes topics related to supply and use of energy in societies. Considering the cost of energy services and associated value gives economic meaning to the efficiency at which energy can be produced. Energy services can be defined as functions that generate and provide energy to the “desired end services or states”. The efficiency of energy services is dependent on the engineered technology used to produce and supply energy. The goal is to minimise energy input required to produce the energy service, such as lighting (lumens), heating (temperature) and fuel. The main sectors considered in energy economics are transportation and building, although it is relevant to a broad scale of human activities, including households and businesses at a microeconomic level and resource management and environmental impacts at a macroeconomic level.

In economics, Dutch disease is the apparent causal relationship between the increase in the economic development of a specific sector and a decline in other sectors.

The exploitation of natural resources describes using natural resources, often non-renewable or limited, for economic growth or development. Environmental degradation, human insecurity, and social conflict frequently accompany natural resource exploitation. The impacts of the depletion of natural resources include the decline of economic growth in local areas; however, the abundance of natural resources does not always correlate with a country's material prosperity. Many resource-rich countries, especially in the Global South, face distributional conflicts, where local bureaucracies mismanage or disagree on how resources should be utilized. Foreign industries also contribute to resource exploitation, where raw materials are outsourced from developing countries, with the local communities receiving little profit from the exchange. This is often accompanied by negative effects of economic growth around the affected areas such as inequality and pollution

Trade justice is a campaign by non-governmental organisations, plus efforts by other actors, to change the rules and practices of world trade in order to promote fairness. These organizations include consumer groups, trade unions, faith groups, aid agencies and environmental groups.

The resource curse, also known as the paradox of plenty or the poverty paradox, is the phenomenon of countries with an abundance of natural resources having less economic growth, less democracy, or worse development outcomes than countries with fewer natural resources. There are many theories and much academic debate about the reasons for and exceptions to the adverse outcomes. Most experts believe the resource curse is not universal or inevitable but affects certain types of countries or regions under certain conditions.

Mining in Australia has long been a significant primary sector industry and contributor to the Australian economy by providing export income, royalty payments and employment. Historically, mining booms have also encouraged population growth via immigration to Australia, particularly the gold rushes of the 1850s. Many different ores, gems and minerals have been mined in the past and a wide variety are still mined throughout the country.

The Western Australian economy is a state economy dominated by its resources and services sector and largely driven by the export of iron-ore, gold, liquefied natural gas and agricultural commodities such as wheat. Covering an area of 2.5 million km2, the state is Australia's largest, accounting for almost one-third of the continent. Western Australia is the nation's fourth most populous state, with 2.6 million inhabitants.

Energy independence is independence or autarky regarding energy resources, energy supply and/or energy generation by the energy industry.

Hydrocarbon economy is a term referencing the global hydrocarbon industry and its relationship to world markets. Energy used mostly comes from three hydrocarbons: petroleum, coal, and natural gas. Hydrocarbon economy is often used when talking about possible alternatives like the hydrogen economy.

The mining industry of Botswana has dominated the national economy of Botswana since the 1970s, being a primary sector industry. Diamond has been the leading component of the mineral sector ever since production of gems started being extracted by the mining company Debswana. Most of Botswana's diamond production is of gem quality, resulting in the country's position as the world's leading producer of diamond by value. Copper, gold, nickel, coal and soda ash production also has held significant, though smaller, roles in the economy.

Mining is the biggest contributor to Namibia's economy in terms of revenue. It accounts for 25% of the country's income. Its contribution to the gross domestic product is also very important and makes it one of the largest economic sectors of the country. Namibia produces diamonds, uranium, copper, magnesium, zinc, silver, gold, lead, semi-precious stones and industrial minerals. The majority of revenue comes from diamond mining. In 2014, Namibia was the fourth-largest exporter of non-fuel minerals in Africa.

The mineral industry of Peru has played an important role in the nation's history and been integral to the country's economic growth for several decades. The industry has also contributed to environmental degradation and environmental injustice; and is a source of environmental conflicts that shape public debate on good governance and development.

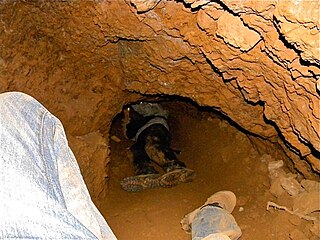

Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) is a blanket term for a type of subsistence mining involving a miner who may or may not be officially employed by a mining company but works independently, mining minerals using their own resources, usually by hand.

Peak minerals marks the point in time when the largest production of a mineral will occur in an area, with production declining in subsequent years. While most mineral resources will not be exhausted in the near future, global extraction and production has become more challenging. Miners have found ways over time to extract deeper and lower grade ores with lower production costs. More than anything else, declining average ore grades are indicative of ongoing technological shifts that have enabled inclusion of more 'complex' processing – in social and environmental terms as well as economic – and structural changes in the minerals exploration industry and these have been accompanied by significant increases in identified Mineral Reserves.

The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) is an independent think tank founded in 1990 working to shape and inform international policy on sustainable development governance. The institute has three offices in Canada - Winnipeg, Ottawa, and Toronto, and one office in Geneva, Switzerland. It has over 150 staff and associates working in over 30 countries.

A global value chain (GVC) refers to the full range of activities that economic actors engage in to bring a product to market. The global value chain does not only involve production processes, but preproduction and postproduction processes.

Environmental conflicts, socio-environmental conflict or ecological distribution conflicts (EDCs) are social conflicts caused by environmental degradation or by unequal distribution of environmental resources. The Environmental Justice Atlas documented 3,100 environmental conflicts worldwide as of April 2020 and emphasised that many more conflicts remained undocumented.

References

- ↑ Gordon, Richard L., and John E. Tilton. "Mineral economics: Overview of a discipline." Resources policy 33, no. 1 (2008): 4-11.

- ↑ "mineral economics". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Eggert, Roderick G. (2008-03-01). "Trends in mineral economics: Editorial retrospective, 1989–2006". Resources Policy. 33 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2007.11.002. ISSN 0301-4207.

- 1 2 3 4 Gordon, Richard L.; Tilton, John E. (2008-03-01). "Mineral economics: Overview of a discipline". Resources Policy. 33 (1): 4–11. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2008.01.003. ISSN 0301-4207.

- 1 2 3 Guerin, Turlough F. (2020-10-01). "Perceptions of supplier impacts on sustainable development in the mining and minerals sector: a survey analysing opportunities and barriers from an Australian perspective". Mineral Economics. 33 (3): 375–388. doi:10.1007/s13563-020-00224-5. ISSN 2191-2211. S2CID 219006011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 corporateName=Commonwealth Parliament; address=Parliament House, Canberra. "The minerals sector". www.aph.gov.au. Retrieved 2022-05-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 corporateName=Commonwealth Parliament; address=Parliament House, Canberra. "Sustainable Development and the Australian Minerals Sector". www.aph.gov.au. Retrieved 2022-05-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 Walser, G. (2002). "Economic impact of world mining".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Addison, Tony; Roe, Alan, eds. (2018-11-22). Extractive Industries. WIDER Studies in Development Economics. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198817369.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-881736-9.

- 1 2 3 Christmann, Patrice (2021-07-01). "Mineral Resource Governance in the 21st Century and a sustainable European Union". Mineral Economics. 34 (2): 187–208. doi:10.1007/s13563-021-00265-4. ISSN 2191-2211. PMC 8059114 .

- ↑ Davis, Graham A (1998-12-01). "The minerals sector, sectoral analysis, and economic development". Resources Policy. 24 (4): 217–228. doi:10.1016/S0301-4207(98)00034-8. ISSN 0301-4207.

- 1 2 3 Gittins, Ross (2017-02-03). "Mining's economic contribution not as big as you might think". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- 1 2 Mainardi, S (1997-02-01). "Mineral resources and economic development: A survey". Development Southern Africa. 14 (1): 61–77. doi:10.1080/03768359708439950. ISSN 0376-835X.

- 1 2 3 4 Bardi, Ugo (2013). "The Mineral Question: How Energy and Technology Will Determine the Future of Mining". Frontiers in Energy Research. 1. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2013.00009 . ISSN 2296-598X.