Related Research Articles

Zooarchaeology is a hybrid discipline that combines zoology and archaeology. Zooarchaeologists, also called archaeozoologists and faunal analysts, study animal remains from archaeological sites. Faunal remains are the items left behind when an animal dies. These include bones, shells, hair, chitin, scales, hides, proteins and DNA. Bones and shell are the best preserved at archaeological sites. Most of the time, faunal remains do not survive. They may decompose or break because of various circumstances. This can cause difficulties in identifying the remains and interpreting their significance.

Forensic anthropology is the application of the anatomical science of anthropology and its various subfields, including forensic archaeology and forensic taphonomy, in a legal setting. A forensic anthropologist can assist in the identification of deceased individuals whose remains are decomposed, burned, mutilated or otherwise unrecognizable, as might happen in a plane crash. Forensic anthropologists are also instrumental in the investigation and documentation of genocide and mass graves. Along with forensic pathologists, forensic dentists, and homicide investigators, forensic anthropologists commonly testify in court as expert witnesses. Using physical markers present on a skeleton, a forensic anthropologist can potentially determine a person's age, sex, stature, and race. In addition to identifying physical characteristics of the individual, forensic anthropologists can use skeletal abnormalities to potentially determine cause of death, past trauma such as broken bones or medical procedures, as well as diseases such as bone cancer.

Palaeozoology, also spelled as Paleozoology, is the branch of paleontology, paleobiology, or zoology dealing with the recovery and identification of multicellular animal remains from geological contexts, and the use of these fossils in the reconstruction of prehistoric environments and ancient ecosystems.

Environmental archaeology is a sub-field of archaeology which emerged in 1970s and is the science of reconstructing the relationships between past societies and the environments they lived in. The field represents an archaeological-palaeoecological approach to studying the palaeoenvironment through the methods of human palaeoecology. Reconstructing past environments and past peoples' relationships and interactions with the landscapes they inhabited provides archaeologists with insights into the origin and evolution of anthropogenic environments, and prehistoric adaptations and economic practices.

The term bioarchaeology has been attributed to British archaeologist Grahame Clark who, in 1972, defined it as the study of animal and human bones from archaeological sites. Redefined in 1977 by Jane Buikstra, bioarchaeology in the United States now refers to the scientific study of human remains from archaeological sites, a discipline known in other countries as osteoarchaeology, osteology or palaeo-osteology. Compared to bioarchaeology, osteoarchaeology is the scientific study that solely focus on the human skeleton. The human skeleton is used to tell us about health, lifestyle, diet, mortality and physique of the past. Furthermore, palaeo-osteology is simple the study of ancient bones.

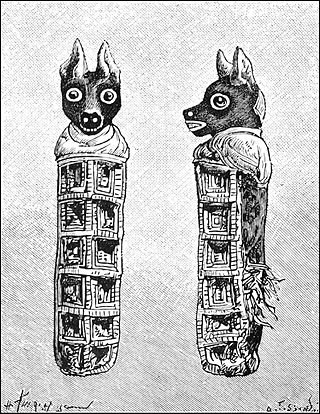

Paleopathology, also spelled palaeopathology, is the study of ancient diseases and injuries in organisms through the examination of fossils, mummified tissue, skeletal remains, and analysis of coprolites. Specific sources in the study of ancient human diseases may include early documents, illustrations from early books, painting and sculpture from the past. Looking at the individual roots of the word "Paleopathology" can give a basic definition of what it encompasses. "Paleo-" refers to "ancient, early, prehistoric, primitive, fossil." The suffix "-pathology" comes from the Latin pathologia meaning "study of disease." Through the analysis of the aforementioned things, information on the evolution of diseases as well as how past civilizations treated conditions are both valuable byproducts. Studies have historically focused on humans, but there is no evidence that humans are more prone to pathologies than any other animal.

In disciplines including archaeology, forensic anthropology, bioarchaeology, osteoarchaeology and zooarchaeology, the number of identified specimens, or NISP, is defined as the number of identified specimens for a specific site or skeleton. It is used to estimate how many people or animals are present in a cluster of bones.

Osteometry is the study and measurement of the human or animal skeleton, especially in an anthropological or archaeological context. In Archaeology it has been used to various ends in the subdisciplines of Zooarchaeology and Bioarchaeology.

The Robert J. Terry Anatomical Skeletal Collection is a collection of some 1,728 human skeletons held by the Department of Anthropology of the National Museum of Natural History of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., United States.

Skeletonization is the state of a dead organism after undergoing decomposition. Skeletonization refers to the final stage of decomposition, during which the last vestiges of the soft tissues of a corpse or carcass have decayed or dried to the point that the skeleton is exposed. By the end of the skeletonization process, all soft tissue will have been eliminated, leaving only disarticulated bones.

Ruins of León Viejo is a World Heritage Site in Nicaragua. It was the original location of León. It is the present location of the town of Puerto Momotombo in the Municipality of La Paz Centro of the Department of León. It is administered by the Instituto Nicaragüense de Cultura.

Archaeobiology, the study of the biology of ancient times through archaeological materials, is a subspecialty of archaeology. It can be seen as a blanket term for paleobotany, animal osteology, zooarchaeology, microbiology, and many other sub-disciplines. Specifically, plant and animal remains are also called ecofacts. Sometimes these ecofacts can be left by humans and sometimes they can be naturally occurring. Archaeobiology tends to focus on more recent finds, so the difference between archaeobiology and palaeontology is mainly one of date: archaeobiologists typically work with more recent, non-fossilised material found at archaeological sites. Only very rarely are archaeobiological excavations performed at sites with no sign of human presence.

EwaElvira Klonowski is a forensic anthropologist. She took political refuge in Iceland in 1981, following the declaration of martial law in the People's Republic of Poland. She has been living in Reykjavik, Iceland since 1982. In 1996, she began working on individual and mass graves exhumation in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Since then, she has been responsible for the excavation and identification of over 2,000 victims, and in 2005 she was nominated to the list of the 1,000 Women for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Stillwater Marsh is an archaeology locality in the Carson Sink in eastern Nevada discovered when heavy flooding in the 1980s unearthed many human remains. The great diversity in plant life and altitudinally-determined microenvironments that surrounded the marsh helped to make it a popular place to live, as evidenced by archaeological findings. At Stillwater Marsh, skeletal remains were the primary means used to determine how people lived in the area. As large numbers of skeletons had not previously been found at Great Basin sites, Stillwater Marsh offered a remarkable opportunity to learn about daily life, as reflected in the human remains.

Phum Snay is an Iron Age archaeological site discovered in May 2000 in Preah Neat Prey District, Banteay Meanchey Province, Northwest Cambodia, around 80 km (50 mi) from the temple ruins of Angkor. The site was excavated between 2001 and 2003 by primary excavators Dougald O’Reilly of the Australian National University, Pheng Sitha and Thuy Chanthourn. The excavation was intended to discover more about Iron Age life in Cambodia.

Krapina Neanderthal site, also known as Hušnjakovo Hill is a Paleolithic archaeological site located near Krapina, Croatia.

Mortuary archaeology is the study of human remains in their archaeological context. This is a known sub-field of bioarchaeology, which is a field that focuses on gathering important information based on the skeleton of an individual. Bioarchaeology stems from the practice of human osteology which is the anatomical study of skeletal remains. Mortuary archaeology, as well as the overarching field it resides in, aims to generate an understanding of disease, migration, health, nutrition, gender, status, and kinship among past populations. Ultimately, these topics help to produce a picture of the daily lives of past individuals. Mortuary archaeologists draw upon the humanities, as well as social and hard sciences to have a full understanding of the individual.

Near Eastern bioarchaeology covers the study of human skeletal remains from archaeological sites in Cyprus, Egypt, Levantine coast, Jordan, Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Yemen.

The Achavanich Beaker Burial refers to the remains of a prehistoric woman who lived around 4,000 years ago in the area of present day Achavanich, Caithness, Scotland. Ava, as she is now known, was discovered in 1987 by William and Graham Ganson and excavated by regional archaeologist Robert Gourlay, from the Highland Regional Council, and two assistant archaeologists: Gemma Corcoran and Sarah Hargreaves. Ava was found interred in a burial cist with a beaker, flints, a cow scapula, and possibly flowers.

Theodore Elmer White (1905–1977), also known as "Ted" or "Doc", was an American paleontologist and zooarchaeologist. White pioneered the use of animal remains as indicators of human behavior in archaeological settings. He also helped develop the Minimum Number of Individuals (MNI) system, which helps archaeologists determine the minimum number of individuals represented within a skeletal assemblage.

References

- ↑ Klein, Richard G.; Kathryn Cruz-Uribe (1984). The Analysis of Animal Bones from Archaeological Sites. US: The University of Chicago Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-226-43958-5.