The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age culture which was centered on the island of Crete. Known for its monumental architecture and its energetic art, it is often regarded as the first civilization in Europe.

A larnax is a type of small closed coffin, box or "ash-chest" often used in the Minoan civilization and in Ancient Greece as a container for human remains—either a corpse or cremated ashes.

Tomb KV17, located in Egypt's Valley of the Kings, is the tomb of Pharaoh Seti I of the Nineteenth Dynasty. It is also known by the names "Belzoni's tomb", "the Tomb of Apis", and "the Tomb of Psammis, son of Nechois". It is one of the most decorated tombs in the valley, and is one of the largest and deepest tombs in the Valley of the Kings. It was uncovered by Italian archaeologist and explorer Giovanni Battista Belzoni on 16 October 1817.

Tomb WV23, also known as KV23, is located in the Western Valley of the Kings near modern-day Luxor, and was the tomb of Pharaoh Ay of the Eighteenth Dynasty. The tomb was discovered by Giovanni Battista Belzoni in the winter of 1816. Its architecture is similar to that of the tomb of Akhenaten, with a straight descending corridor leading to a "well chamber" that has no shaft. This leads to the burial chamber, which now contains the reconstructed sarcophagus, which had been smashed in antiquity. The tomb had also been anciently desecrated, with many instances of Ay's image or name erased from the wall paintings. Its decoration is similar in content and colour to that of the tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62), with a few differences. On the eastern wall there is a depiction of a fishing and fowling scene, which is not shown in other royal tombs, normally appearing in burials of nobility.

Tomb KV43 is the tomb of Pharaoh Thutmose IV in the Valley of the Kings in Luxor, Egypt. It has a dog-leg shape, typical of the layout of early 18th Dynasty tombs. KV43 was rediscovered in 1903 by Howard Carter, excavating on behalf of Theodore M. Davis.

Aegean art is art that was created in the lands surrounding, and the islands within, the Aegean Sea during the Bronze Age, that is, until the 11th century BC, before Ancient Greek art. Because is it mostly found in the territory of modern Greece, it is sometimes called Greek Bronze Age art, though it includes not just the art of the Mycenaean Greeks, but also that of the non-Greek Cycladic and Minoan cultures, which converged over time.

Minoan pottery has been used as a tool for dating the mute Minoan civilization. Its restless sequence of quirky maturing artistic styles reveals something of Minoan patrons' pleasure in novelty while they assist archaeologists in assigning relative dates to the strata of their sites. Pots that contained oils and ointments, exported from 18th century BC Crete, have been found at sites through the Aegean islands and mainland Greece, in Cyprus, along coastal Syria and in Egypt, showing the wide trading contacts of the Minoans.

Two Minoan snake goddess figurines were excavated in 1903 in the Minoan palace at Knossos in the Greek island of Crete. The decades-long excavation programme led by the English archaeologist Arthur Evans greatly expanded knowledge and awareness of the Bronze Age Minoan civilization, but Evans has subsequently been criticised for overstatements and excessively speculative ideas, both in terms of his "restoration" of specific objects, including the most famous of these figures, and the ideas about the Minoans he drew from the archaeology. The figures are now on display at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum (AMH).

Minoan religion was the religion of the Bronze Age Minoan civilization of Crete. In the absence of readable texts from most of the period, modern scholars have reconstructed it almost totally on the basis of archaeological evidence of such as Minoan paintings, statuettes, vessels for rituals and seals and rings. Minoan religion is considered to have been closely related to Near Eastern ancient religions, and its central deity is generally agreed to have been a goddess, although a number of deities are now generally thought to have been worshipped. Prominent Minoan sacred symbols include the bull and the horns of consecration, the labrys double-headed axe, and possibly the serpent.

Minoan art is the art produced by the Bronze Age Aegean Minoan civilization from about 3000 to 1100 BC, though the most extensive and finest survivals come from approximately 2300 to 1400 BC. It forms part of the wider grouping of Aegean art, and in later periods came for a time to have a dominant influence over Cycladic art. Since wood and textiles have decomposed, the best-preserved surviving examples of Minoan art are its pottery, palace architecture, small sculptures in various materials, jewellery, metal vessels, and intricately-carved seals.

The Ludovisi Battle sarcophagus or "Great" Ludovisi sarcophagus is an ancient Roman sarcophagus dating to around AD 250–260, found in 1621 in the Vigna Bernusconi, a tomb near the Porta Tiburtina. It is also known as the Via Tiburtina Sarcophagus, though other sarcophagi have been found there. It is known for its densely populated, anti-classical composition of "writhing and highly emotive" Romans and Goths, and is an example of the battle scenes favored in Roman art during the Crisis of the Third Century. Discovered in 1621 and named for its first modern owner, Ludovico Ludovisi, the sarcophagus is now displayed at the Palazzo Altemps in Rome, part of the National Museum of Rome as of 1901.

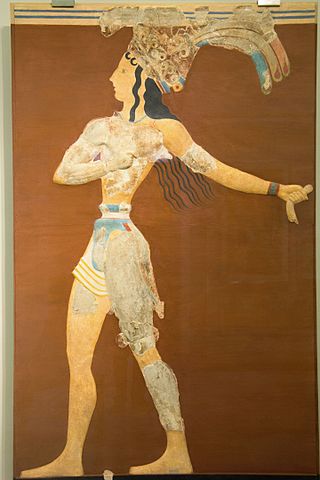

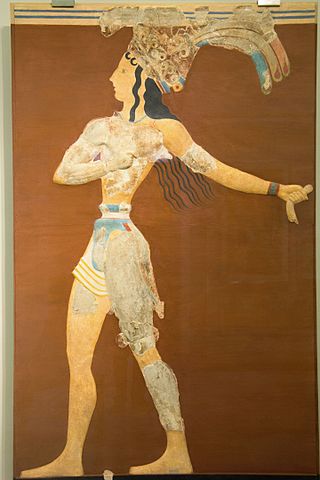

The Prince of the Lilies, or the Lily Prince or Priest-King Fresco, is a celebrated Minoan painting excavated in pieces from the palace of Knossos, capital of the Bronze Age Minoan civilization on the Greek island of Crete. The mostly reconstructed original is now in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum (AMH), with a replica version at the palace which includes flowers in the background.

The Hagia Triada Sarcophagus is a late Minoan 137 cm (54 in)-long limestone sarcophagus, dated to around 1400 BC or some decades later, excavated from a chamber tomb at Hagia Triada, Crete in 1903 and now on display at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum (AMH) in Crete, Greece.

Campana reliefs are Ancient Roman terracotta reliefs made from the middle of the first century BC until the first half of the second century AD. They are named after the Italian collector Giampietro Campana, who first published these reliefs (1842).

Minoan seals are impression seals in the form of carved gemstones and similar pieces in metal, ivory and other materials produced in the Minoan civilization. They are an important part of Minoan art, and have been found in quantity at specific sites, for example in Knossos, Mallia and Phaistos. They were evidently used as a means of identifying documents and objects.

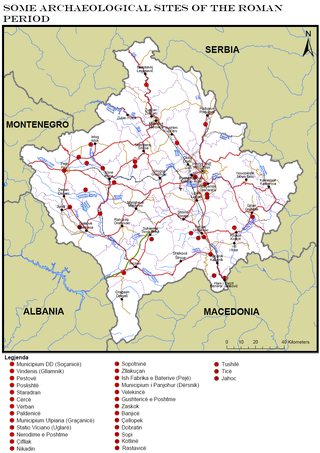

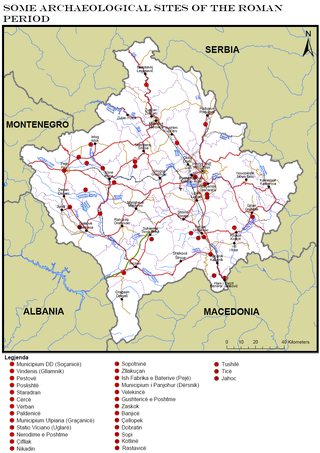

Part of a series of articles upon Archaeology of Kosovo

The Tomb of the Palmettes, sometimes known as the Rhomiopoulou Tomb, is an ancient Macedonian tomb of the Hellenistic period in Mieza, Macedonia, Greece, noted for the quality of its painted decoration. It was built in the first half of the third century BC.

The Tomb of Macridy Bey (Greek: Τάφος Μακρίδη Μπέη, romanized: tafos makridi bei, also known as the Tomb of Langadas, is an ancient Macedonian tomb of the Classical or early Hellenistic period, on the site of ancient Lete, modern Derveni between Thessaloniki and Langadas, in Central Macedonia, Greece. A number of cist graves and a single chamber tomb are located in the vicinity. The structure seems to date to the late fourth or early third century BCE.

Paul Küppers was a German art historian and first husband of Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers. He was a co-founder of the Kestner Society and brought contemporary art to Hanover.

The Recep Pasha Mosque is a historical Ottoman mosque on the island of Rhodes, Greece, one of the seven mosques inside the old walled city of Rhodes. As of 2022, it is not open for either worship or visit, due to the poor condition it is in.