The Huilliche, Huiliche or Huilliche-Mapuche are the southern partiality of the Mapuche macroethnic group in Chile and Argentina. Located in the Zona Sur, they inhabit both Futahuillimapu and, as the Cunco or Veliche subgroup, the north half of Chiloé Island. The Huilliche are the principal indigenous people of those regions. According to Ricardo E. Latcham the term Huilliche started to be used in Spanish after the second founding of Valdivia in 1645, adopting the usage of the Mapuches of Araucanía for the southern Mapuche tribes. Huilliche means 'southerners' A genetic study showed significant affinities between Huilliches and indigenous peoples east of the Andes, which suggests but does not prove a partial origin in present-day Argentina.

Neuquén is a province of Argentina, located in the west of the country, at the northern end of Patagonia. It borders Mendoza Province to the north, Rio Negro Province to the southeast, and Chile to the west. It also meets La Pampa Province at its northeast corner.

San Carlos de Bariloche, usually known as Bariloche, is a city in the province of Río Negro, Argentina, situated in the foothills of the Andes on the southern shores of Nahuel Huapi Lake. It is located within the Nahuel Huapi National Park. After development of extensive public works and Alpine-styled architecture, the city emerged in the 1930s and 1940s as a major tourism centre with skiing, trekking and mountaineering facilities. In addition, it has numerous restaurants, cafés, and chocolate shops. The city had a permanent population of 108,205 according to the 2010 census. According to the latest statistics from 2015, the population is around 122,700, and a projection for 2020 estimates 135,704.

San Martín de los Andes is a city in the south-west of the province of Neuquén, Argentina, serving as the administration centre of the Lácar Department. Lying at the foot of the Andes, on the Lácar lake, it is considered one of the main tourism destinations in the province. The National Route 40 runs to the city, connecting it with important touristic points in the south of the province, such as Lanín and Nahuel Huapí national parks.

The Gulf of Penas is a body of water located south of the Taitao Peninsula, Chile.

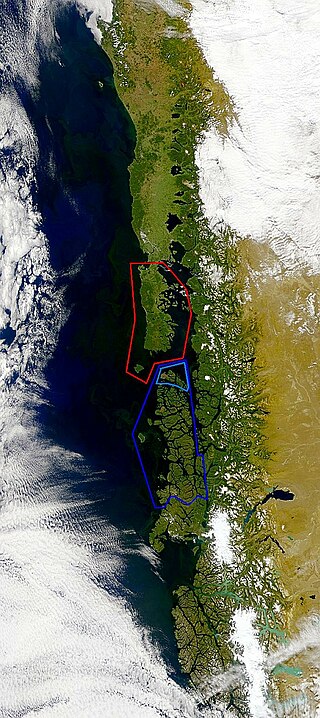

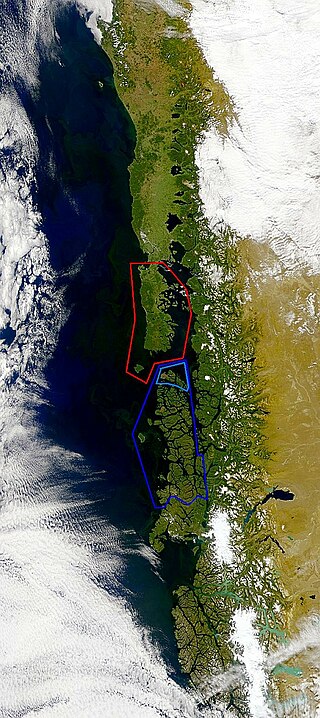

The Chiloé Archipelago is a group of islands lying off the coast of Chile, in the Los Lagos Region. It is separated from mainland Chile by the Chacao Channel in the north, the Sea of Chiloé in the east and the Gulf of Corcovado in the southeast. All islands except the Desertores Islands form Chiloé Province. The main island is Chiloé Island. Of roughly rectangular shape, the southwestern half of this island is a wilderness of contiguous forests, wetlands and, in some places, mountains. The landscape of the northeastern sectors of Chiloé Island and the islands to the east is dominated by rolling hills, with a mosaic of pastures, forests and cultivated fields.

Guaitecas Archipelago is a sparsely populated archipelago in the Aisén region of Chile. The archipelago is made up of eight main islands and numerous smaller ones. The eight largest islands are from northwest to southeast: Gran Guaiteca, Ascención, Betecoy, Clotilde, Leucayec, Elvira, Sánchez and Mulchey. The islands have subdued topography compared to the Andes, with Gran Guaiteca containing the archipelago's high point at 369 m (1,211 ft).

The Chono, or Guaiteco were a nomadic indigenous people or group of peoples of the archipelagos of Chiloé, Guaitecas and Chonos.

Cuncos or Juncos is a poorly known subgroup of Huilliche people native to coastal areas of southern Chile and the nearby inland. Mostly a historic term, Cuncos are chiefly known for their long-running conflict with the Spanish during the colonial era of Chilean history.

Nahuel Huapi National Park is the oldest national park in Argentina, established in 1934. It surrounds Nahuel Huapi Lake in the foothills of the Patagonian Andes. The largest of the national parks in the region, it has an area of 7,050 km2 (2,720 sq mi), or nearly 2 million acres. Its landscapes represent the north Patagonian Andean Zone consisting of three types, namely, the Altoandino, the Andino-Patagónico and the Patagonian steppe. It also represents small parts of the Valdivian Rainforest.

Nicolás Mascardi was a Ligurian Jesuit priest and missionary in South America in the 17th century. He arrived to Chile in 1651. While active in Araucanía he gained notoriety for the exorcisms he practised among the Mapuches.

The Huilliche uprising of 1712 was an indigenous uprising against the Spanish encomenderos of the Chiloé Archipelago, which was then a part of the Captaincy General of Chile. The rebellion took place in the central part of the archipelago.

In Colonial times the Spanish Empire diverted significant resources to fortify the Chilean coast as consequence of Dutch and English raids. The Spanish attempts to block the entrance of foreign ships to the eastern Pacific proved fruitless due to the failure to settle the Strait of Magellan and the discovery of the Drake Passage. As result of this the Spanish settlement at Chiloé Archipelago became a centre from where the west coast of Patagonia was protected from foreign powers. In face of the international wars that involved the Spanish Empire in the second half of the 18th century the Crown was unable to directly protect peripheral colonies like Chile leading to local government and militias assuming the increased responsibilities.

In Colonial times the Spanish Empire diverted significant resources to fortify the Chilean coast as a consequence of Dutch and English raids. During the 16th century the Spanish strategy was to complement the fortification work in its Caribbean ports with forts in the Strait of Magellan. As attempts at settling and fortifying the Strait of Magellan were abandoned the Spanish began to fortify the Captaincy General of Chile and other parts of the west coast of the Americas. The coastal fortifications and defense system was at its peak in the mid-18th century.

Juan Antonio Garretón was a Spanish army officer who served in different positions in Colonial Chile and Chiloé.

The Governorate of Chiloé was political and military subdivision of the Spanish Empire that existed, with a 1784–1789 interregnum, from 1567 to 1826. The Governorate of Chiloé depended on the Captaincy General of Chile until the late 18th century when it was made dependent directly on the Viceroyalty of Peru. The administrative change was done simultaneously as the capital of the archipelago was moved from Castro to Ancud in 1768. The last Royal Governor of Chiloé, Antonio de Quintanilla, depended directly on the central government in Madrid.

The Antonio de Vea expedition of 1675–1676 was a Spanish naval expedition to the fjords and channels of Patagonia aimed to find whether rival colonial powers—specifically, the English—were active in the region. While this was not the first Spanish expedition to the region, it was the largest up to then, involving 256 men, one ocean-going ship, two long boats and nine dalcas. The expedition dispelled suspicion about English bases in Patagonia. Spanish authorities' knowledge of western Patagonia was greatly improved by the expedition, yet Spanish interest in the area waned thereafter until the 1740s.

The Huilliche uprising of 1792 was an indigenous uprising against the Spanish penetration into Futahuillimapu, territory in southern Chile that had been de facto free of Spanish rule since 1602. The first part of the conflict was a series of Huilliche attacks on Spanish settlers and the mission in the frontier next to Bueno River. Following this a militia in charge of Tomás de Figueroa departed from Valdivia ravaging Huilliche territory in a quest to subdue anti-Spanish elements in Futahuillimapu.

In the late 16th century, the Spanish Empire attempted to settle the Strait of Magellan with the aim of controlling the only known passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans at the time. The project was a direct response to Francis Drake's unexpected entry into the Pacific through the strait in 1578 and the subsequent havoc his men wreaked upon the Pacific coast of Spanish America. The colonization effort took the form of a naval expedition led by veteran explorer Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa, which set sail from Cádiz in December 1581. The expedition established two short-lived settlements in the strait, Nombre de Jesús and Ciudad del Rey Don Felipe. However, the settlers proved poorly prepared for the cool and windy environment of the strait, and starvation and disease was soon rampant. A resupply expedition organized by Sarmiento in Río de Janeiro in 1585 was unable to reach the strait due to unfavorable weather. Aid to the struggling colony was later hampered by Sarmiento falling prisoner to English corsairs in 1586 and the unresponsivity of King Philip II, likely due to the strain of Spain's resources caused by the wars with England and Dutch rebels. The last known survivor was rescued by a passing ship in 1590.

By the late 1660s, the English rulers had considered invading Spanish-ruled Chile for several years. In 1655, Simón de Casseres proposed to Oliver Cromwell a plan to take over Chile with only four ships and thousand men.