Systemic scleroderma, or systemic sclerosis, is an autoimmune rheumatic disease characterised by excessive production and accumulation of collagen, called fibrosis, in the skin and internal organs and by injuries to small arteries. There are two major subgroups of systemic sclerosis based on the extent of skin involvement: limited and diffuse. The limited form affects areas below, but not above, the elbows and knees with or without involvement of the face. The diffuse form also affects the skin above the elbows and knees and can also spread to the torso. Visceral organs, including the kidneys, heart, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract can also be affected by the fibrotic process. Prognosis is determined by the form of the disease and the extent of visceral involvement. Patients with limited systemic sclerosis have a better prognosis than those with the diffuse form. Death is most often caused by lung, heart, and kidney involvement. The risk of cancer is increased slightly.

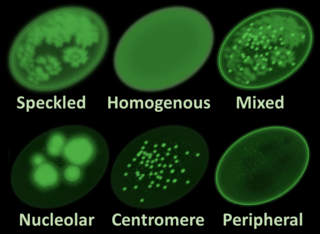

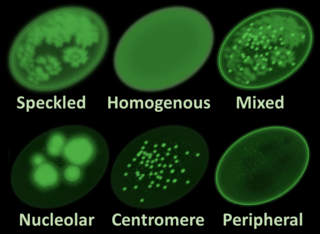

Antinuclear antibodies are autoantibodies that bind to contents of the cell nucleus. In normal individuals, the immune system produces antibodies to foreign proteins (antigens) but not to human proteins (autoantigens). In some cases, antibodies to human antigens are produced.

Kikuchi disease was described in 1972 in Japan. It is also known as histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, Kikuchi necrotizing lymphadenitis, phagocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, subacute necrotizing lymphadenitis, and necrotizing lymphadenitis. Kikuchi disease occurs sporadically in people with no family history of the condition.

Raynaud syndrome, also known as Raynaud's phenomenon, is a medical condition in which the spasm of small arteries causes episodes of reduced blood flow to end arterioles. Typically, the fingers, and less commonly, the toes, are involved. Rarely, the nose, ears, nipples, or lips are affected. The episodes classically result in the affected part turning white and then blue. Often, numbness or pain occurs. As blood flow returns, the area turns red and burns. The episodes typically last minutes but can last several hours. The condition is named after the physician Auguste Gabriel Maurice Raynaud, who first described it in his doctoral thesis in 1862.

CREST syndrome, also known as the limited cutaneous form of systemic sclerosis (lcSSc), is a multisystem connective tissue disorder. The acronym "CREST" refers to the five main features: calcinosis, Raynaud's phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia.

An autoantibody is an antibody produced by the immune system that is directed against one or more of the individual's own proteins. Many autoimmune diseases are associated with such antibodies.

A connective tissue disease is a disease which involves damage to, or destruction of, any type of connective tissue in the body. Depending on the specific disease, the affected tissue(s) may be a single specific type, a group of several related tissues, or a wide variety of unrelated types of connective tissue. Some of the most common connective tissue diseases involve injury to collagen and elastin as a result of inflammation. Many connective tissue diseases are strongly connected to autoimmune disease processes.

Extractable nuclear antigens (ENAs) are over 100 different soluble cytoplasmic and nuclear antigens. They are known as "extractable" because they can be removed from cell nuclei using saline and represent six main proteins: Ro, La, Sm, RNP, Scl-70, Jo1. Most ENAs are part of spliceosomes or nucleosomes complexes and are a type of small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNPS). The location in the nucleus and association with spliceosomes or nucleosomes results in these ENAs being associated with additional RNA and proteins such as polymerases. This quality of ENAs often makes it difficult to purify and quantify their presence for clinical use.

Palindromic rheumatism (PR) is a syndrome characterised by recurrent, self-resolving inflammatory attacks in and around the joints, and consists of arthritis or periarticular soft tissue inflammation. The course is often acute onset, with sudden and rapidly developing attacks or flares. There is pain, redness, swelling, and disability of one or multiple joints. The interval between recurrent palindromic attacks and the length of an attack is extremely variable from few hours to days. Attacks may become more frequent with time but there is no joint damage after attacks. It is thought to be an autoimmune disease, possibly an abortive form of rheumatoid arthritis.

Scleromyositis, is an autoimmune disease. People with scleromyositis have symptoms of both systemic scleroderma and either polymyositis or dermatomyositis, and is therefore considered an overlap syndrome. Although it is a rare disease, it is one of the more common overlap syndromes seen in scleroderma patients, together with MCTD and Antisynthetase syndrome. Autoantibodies often found in these patients are the anti-PM/Scl (anti-exosome) antibodies.

An overlap syndrome is a medical condition which shares features of at least two more widely recognised disorders. Examples of overlap syndromes can be found in many medical specialties such as overlapping connective tissue disorders in rheumatology, and overlapping genetic disorders in cardiology.

HLA-DR4 (DR4) is an HLA-DR serotype that recognizes the DRB1*04 gene products. The DR4 serogroup is large and has a number of moderate frequency alleles spread over large regions of the world.

Anti-topoisomerase antibodies (ATA) are autoantibodies directed against topoisomerase and found in several diseases, most importantly scleroderma. Diseases with ATA are autoimmune disease because they react with self-proteins. They are also referred to as anti-DNA topoisomerase I antibody.

Lupus erythematosus is a collection of autoimmune diseases in which the human immune system becomes hyperactive and attacks healthy tissues. Symptoms of these diseases can affect many different body systems, including joints, skin, kidneys, blood cells, heart, and lungs. The most common and most severe form is systemic lupus erythematosus.

Anti-double stranded DNA (Anti-dsDNA) antibodies are a group of anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) the target antigen of which is double stranded DNA. Blood tests such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunofluorescence are routinely performed to detect anti-dsDNA antibodies in diagnostic laboratories. They are highly diagnostic of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and are implicated in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis.

Lupus, technically known as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), is an autoimmune disease in which the body's immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue in many parts of the body. Symptoms vary among people and may be mild to severe. Common symptoms include painful and swollen joints, fever, chest pain, hair loss, mouth ulcers, swollen lymph nodes, feeling tired, and a red rash which is most commonly on the face. Often there are periods of illness, called flares, and periods of remission during which there are few symptoms.

Lupus headache is a proposed, specific headache disorder in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Research shows that headache is a symptom commonly described by SLE patients —57% in one meta-analysis, ranging in different studies from 33% to 78%; of which migraine 31.7% and tension-type headache 23.5%. The existence of a special lupus headache is contested, although few high-quality studies are available to form definitive conclusions.

Undifferentiated connective tissue disease (UCTD) is a disease in which the connective tissues are targeted by the immune system. It is a serological and clinical manifestation of an autoimmune disease. When there is proof of an autoimmune disease, it will be diagnosed as UCTD if the disease doesn't answer to any criterion of specific autoimmune disease. This is also the case of major rheumatic diseases whose early phase was defined by LeRoy et al. in 1980 as undifferentiated connective tissue disease.

Anti-SSA autoantibodies are a type of anti-nuclear autoantibodies that are associated with many autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), SS/SLE overlap syndrome, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), neonatal lupus and primary biliary cirrhosis. They are often present in Sjögren's syndrome (SS). Additionally, Anti-Ro/SSA can be found in other autoimmune diseases such as systemic sclerosis (SSc), polymyositis/dermatomyositis (PM/DM), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), and are also associated with heart arrhythmia.

Lupus vasculitis is one of the secondary vasculitides that occurs in approximately 50% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).