Related Research Articles

Charles Pinckney was an American Founding Father, planter, and politician who was a signer of the United States Constitution. He was elected and served as the 37th governor of South Carolina, later serving two more non-consecutive terms. He also served as a U.S. Senator and a member of the House of Representatives. He was first cousin once removed of fellow signer Charles Cotesworth Pinckney.

William Johnson Jr. was an American attorney, state legislator, and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1804 until his death in 1834. When he was 32 years old, Johnson was appointed to the Supreme Court by President Thomas Jefferson. He was the first Jeffersonian Republican member of the Court as well as the second Justice from the state of South Carolina. During his tenure, Johnson restored the act of delivering seriatim opinions. He wrote about half of the dissents during the Marshall Court, leading historians to nickname him the "first dissenter".

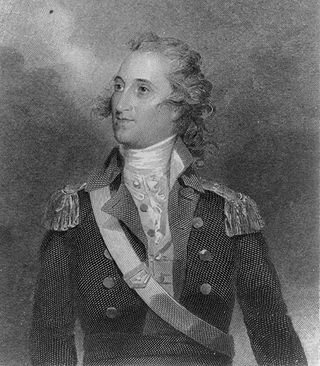

Thomas Pinckney was an American statesman, diplomat, and military officer who fought in both the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, achieving the rank of major general. He served as Governor of South Carolina and as the U.S. minister to Great Britain.

Christopher Gadsden was an American politician who was the principal leader of the South Carolina Patriot movement during the American Revolution. He was a delegate to the Continental Congress, a brigadier general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, Lieutenant Governor of South Carolina, a merchant, and the designer of the Gadsden flag. He is a signatory to the Continental Association.

Denmark Vesey was an 18th-century and early 19th century free Black and community leader in Charleston, South Carolina, who was accused and convicted of planning a major slave revolt in 1822. Although the alleged plot was discovered before it could be realized, its potential scale stoked the fears of the antebellum planter class that led to increased restrictions on both enslaved and free African Americans.

Rawlins Lowndes was an American lawyer, planter and politician who became involved in the patriot cause after his election to South Carolina's legislature, although he opposed independence from the Kingdom of Great Britain. Lowndes served as president/governor of South Carolina during the American Revolutionary War, and after the war opposed his state's ratification of the Constitution of the United States because it would restrict the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Lowndes also served as a state legislator and mayor of Charleston before his death. Two of his sons, Thomas and William Lowndes, would serve in the U.S. Congress.

The Judiciary Act of 1789 was a United States federal statute enacted on September 24, 1789, during the first session of the First United States Congress. It established the federal judiciary of the United States. Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution prescribed that the "judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and such inferior Courts" as Congress saw fit to establish. It made no provision for the composition or procedures of any of the courts, leaving this to Congress to decide.

South Carolina was outraged over British tax policies in the 1760s that violated what they saw as their constitutional right to "no taxation without representation". Merchants joined the boycott against buying British products. When the London government harshly punished Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party, South Carolina's leaders joined eleven other colonies in forming the Continental Congress. When the British attacked Lexington and Concord in the spring of 1775 and were beaten back by the Massachusetts Patriots, South Carolina Patriots rallied to support the American Revolution. Loyalists and Patriots of the colony were split by nearly 50/50.

Antebellum South Carolina is typically defined by historians as South Carolina during the period between the War of 1812, which ended in 1815, and the American Civil War, which began in 1861.

William Loughton Smith was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat from Charleston, South Carolina. He represented South Carolina as a Federalist in the United States House of Representatives from 1789 until 1797, during which time he served as chairman of the Committee on Ways and Means.

An Act to protect the commerce of the United States and punish the crime of piracy is an 1819 United States federal statute against piracy, amended in 1820 to declare participating in the slave trade or robbing a ship to be piracy as well. The last execution for piracy in the United States was of slave trader Nathaniel Gordon in 1862 in New York, under the amended act.

John Faucheraud Grimké was an American jurist who served as Associate justice and Senior Associate Justice of South Carolina's Court of Common Pleas and General Sessions from 1783 until his death. He also served in the South Carolina state legislature from 1782 until 1790. He was intendant (mayor) of Charleston, South Carolina, for two terms, from 1786 to 1788.

John Rutledge was an American Founding Father, politician, and jurist who served as one of the original associate justices of the Supreme Court and the second chief justice of the United States. Additionally, he served as the first president of South Carolina and later as its first governor after the Declaration of Independence was signed.

William Ancrum was a wealthy American merchant, slave trader and indigo planter from Charleston, South Carolina who served in the Third General Assembly during the Revolutionary War (1779—1780). His interest in the economic potential of the Carolina backcountry led to his involvement in the formation of the present-day town of Camden, South Carolina. Of particular value to historians are the William Ancrum Papers, 1757–1789, which are made up of Ancrum's letters and personal account books, currently held by the South Carolina Library at the University of South Carolina. This collection provides insight into the economic impact of the American Revolution on Charleston planters and merchants, from the prices of slaves to restrictions on imports and exports.

Black South Carolinians are residents of the state of South Carolina who are of African ancestry. This article examines South Carolina's history with an emphasis on the lives, status, and contributions of African Americans. Enslaved Africans first arrived in the region in 1526, and the institution of slavery remained until the end of the Civil War in 1865. Until slavery's abolition, the free black population of South Carolina never exceeded 2%. Beginning during the Reconstruction Era, African Americans were elected to political offices in large numbers, leading to South Carolina's first majority-black government. Toward the end of the 1870s however, the Democratic Party regained power and passed laws aimed at disenfranchising African Americans, including the denial of the right to vote. Between the 1870s and 1960s, African Americans and whites lived segregated lives; people of color and whites were not allowed to attend the same schools or share public facilities. African Americans were treated as second-class citizens leading to the civil rights movement in the 1960s. In modern America, African Americans constitute 22% of the state's legislature, and in 2014, the state's first African American U.S. Senator since Reconstruction, Tim Scott, was elected. In 2015, the Confederate flag was removed from the South Carolina Statehouse after the Charleston church shooting.

David Deas was the twelfth intendant of Charleston, South Carolina, serving from 1802 to 1803.

The Negro Law of South Carolina (1848) was one of John Belton O'Neall's longer works.

James Henry Ladson (1795–1868) was an American planter and businessman from Charleston, South Carolina. He was the owner of James H. Ladson & Co., a major Charleston firm that was active in the rice and cotton business, and owned over 200 slaves. He was also the Danish Consul in South Carolina, a director of the State Bank and held numerous other business, church and civic offices. James H. Ladson was a strong proponent of slavery and especially the use of religion to maintain discipline among the slaves. He and other members of the Charleston planter and merchant elite played a key role in launching the American Civil War. Among Ladson's descendants is Ursula von der Leyen, who briefly lived under the alias Rose Ladson.

William Dewitt was a South Carolina planter, lawyer, and politician who was a Captain in the American Revolutionary War. He was a Member of the South Carolina House of Representatives 6 years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. He attended the South Carolina ratifying convention in Charleston. He was one of the delegates that agreed to ratify the Constitution of the United States of America.

In the District of Columbia, the slave trade was legal from its creation until it was outlawed as part of the Compromise of 1850. That restrictions on slavery in the District were probably coming was a major factor in the retrocession of the Virginia part of the District back to Virginia in 1847. Thus the large slave-trading businesses in Alexandria, such as Franklin & Armfield, could continue their operations in Virginia, where slavery was more secure.

References

State Records of South Carolina. Journals of the House of Representatives, 1789-90. Michael Stevens, Christine Allen: Pub. for SCDAH by USC Press: ©1984 SCDAH 1st Ed. Pub. by University of South Carolina Press ISBN 0-87249-944-8 (1511 words)