Dalmatia is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Central Croatia, Slavonia, and Istria, located on the east shore of the Adriatic Sea in Croatia.

Istria is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at the top of the Adriatic between the Gulf of Trieste and the Kvarner Gulf, the peninsula is shared by three countries: Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy, 90% of its area being part of Croatia. Most of Croatian Istria is part of Istria County.

Vlach, also Wallachian, is a term and exonym used from the Middle Ages until the Modern Era to designate speakers of Eastern Romance languages living in Southeast Europe—south of the Danube and north of the Danube.

The Military Frontier was a borderland of the Habsburg monarchy and later the Austrian and Austro-Hungarian Empire. It acted as the cordon sanitaire against incursions from the Ottoman Empire.

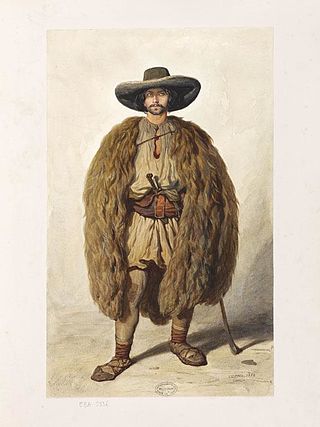

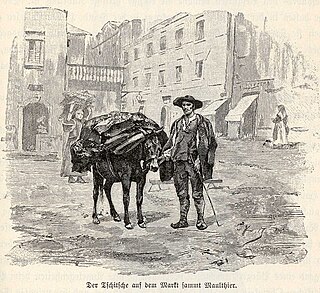

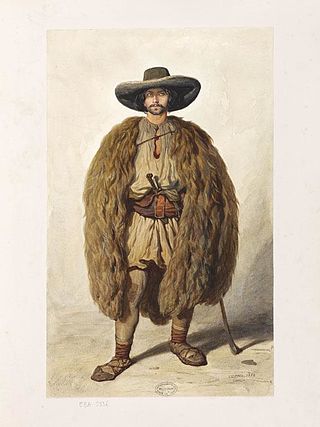

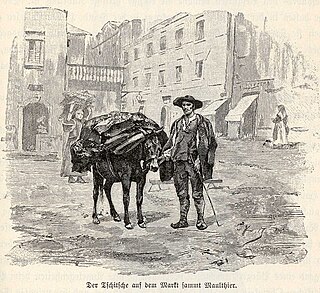

Morlachs has been an exonym used for a rural Christian community in Herzegovina, Lika and the Dalmatian Hinterland. The term was initially used for a bilingual Vlach pastoralist community in the mountains of Croatia from the second half of the 14th until the early 16th century. Then, when the community straddled the Venetian–Ottoman border until the 17th century, it referred only to the Slavic-speaking people of the Dalmatian Hinterland, Orthodox and Catholic, on both the Venetian and Turkish side. The exonym ceased to be used in an ethnic sense by the end of the 18th century, and came to be viewed as derogatory, but has been renewed as a social or cultural anthropological subject. As the nation-building of the 19th century proceeded, the Vlach/Morlach population residing with the Croats and Serbs of the Dalmatian Hinterland espoused either a Serb or Croat ethnic identity, but preserved some common sociocultural outlines.

The Uskoks were irregular soldiers in Habsburg Croatia that inhabited areas on the eastern Adriatic coast and surrounding territories during the Ottoman wars in Europe. Bands of Uskoks fought a guerrilla war against the Ottomans, and they formed small units and rowed swift boats. Since the uskoks were checked on land and were rarely paid their annual subsidy, they resorted to acts of piracy.

The names of Moldavia and Moldova originate from the historical state of Moldavia, which at its greatest extent included eastern Romania, Moldova, and parts of south-western and western Ukraine.

The Vlach law refers to the traditional Romanian common law as well as to various special laws and privileges enjoyed or enforced upon particularly pastoralist communities of Romanian stock or origin in European states of the Late Middle Ages and Early modern period, including in the two Romanian polities of Moldavia and Wallachia, as well as in the Kingdom of Hungary, the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Serbia, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, etc.

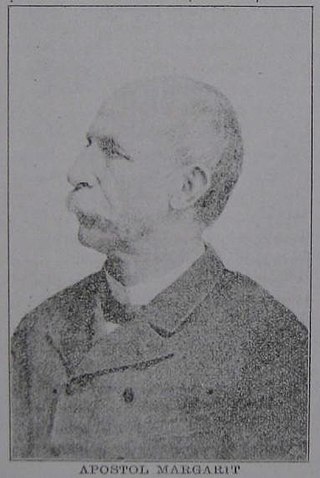

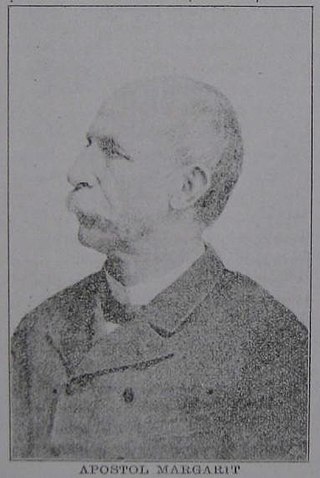

Apostol Mărgărit or Apostolos Margaritis was an Aromanian school teacher and writer. One of the most important voices of Aromanian emancipation in the 19th century, he conditioned Romania's policy toward the Aromanians, who started to have their own schools in their own language, thanks to Mărgărit's efforts.

The Istro-Romanians are a Romance ethnic group native to or associated with the Istrian Peninsula. Historically, they inhabited vast parts of it, as well as the western side of the island of Krk until 1875. However, due to several factors such as the industrialization and modernization of Istria during the socialist regime of Yugoslavia, many Istro-Romanians emigrated to other places, be them Croatian cities such as Pula and Rijeka or places such as New York City, Trieste and Western Australia. The Istro-Romanians dwindled severely in number, being reduced to eight settlements on the Croatian side of Istria in which they do not represent the majority.

Hasanaginica, also Asanaginica, is a South Slavic folk ballad, created during the period of 1646–49, in the region of Imotski, which at the time was a part of the Bosnia Eyalet of the Ottoman Empire.

Alberto Fortis was an Italian writer, naturalist and cartographer, citizen of Republic of Venice.

Italians of Croatia are an autochthonous historical national minority recognized by the Constitution of Croatia. As such, they elect a special representative to the Croatian Parliament. There is the Italian Union of Croatia and Slovenia, which is a Croatian-Slovenian joint organization with its main site in Rijeka, Croatia and its secondary site in Koper, Slovenia.

The term Vlachs was initially used in medieval Croatian and Venetian history for a Romance-speaking pastoralist community, called "Vlachs" and "Morlachs", inhabiting the mountains and lands of the Croatian Kingdom and the Republic of Venice from the early 14th century. By the end of the 15th century they were highly assimilated with the Slavs and lost their language or were at least bilingual, while some communities managed to preserve and continue to speak their language (Istro-Romanians).

Venetian Dalmatia refers to parts of Dalmatia under the rule of the Republic of Venice, mainly from the 15th to the 18th centuries. Dalmatia was first sold to Venice in 1409 but Venetian Dalmatia was not fully consolidated until 1420. It lasted until 1797, when the Republic of Venice fell to the forces of Napoleon Bonaparte and Habsburg Austria.

Ćić is an ethnonym and exonym in a broader sense for all the people who live in the mountainous Ćićarija area in Croatia and Slovenia. Alongside the term Ćiribirci, in the narrow sense, it is an exonym referring to a community of the Istro-Romanians in the village Žejane in a small part of eastern Ćićarija and the villages around the former Lake Čepić west of the Učka range in Istria, Croatia.

Dimitri Atanasescu Hagi Sterjio was an Aromanian tailor and later teacher known for having been the teacher of the first Romanian school in the Balkans for the Aromanians, located at Trnovo, the place where he was born, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire.

The Aromanian diaspora is any ethnically Aromanian population living outside its traditional homeland in the Balkans. The Aromanians are a small Balkan ethnic group living scattered throughout Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, North Macedonia, Romania and Serbia. Historically, they also used to live in other countries such as Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia, although they have ever since been assimilated.

The katun is a rural self-governing community in the Balkans, traditional of the living style of Albanians, Vlachs, as well as some Slavic communities of hill people. Traditionally, a katun is based on strong kinship ties and the practice of a closed farming economy based on stockbreeding, constantly moving to find pasture. The community based its organizational, political and economic activities on the decisions of a council of elders or a senior member appointed as its leader. The Albanian communities strictly followed the Kanun, their traditional customary law that has directed all the aspects of their kinship-based society.

Alvise Badoer was a Venetian patrician, lawyer, administrator and diplomat. He played a major role in the Ottoman–Venetian War of 1537–1540. He advocated for and helped arrange the Holy League in 1537–1538, took command of Venetian Dalmatia in 1538–1539 and negotiated the peace treaty in 1540.