Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution requires U.S. states to provide attorneys to criminal defendants who are unable to afford their own. The case extended the right to counsel, which had been found under the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to impose requirements on the federal government, by imposing those requirements upon the states as well.

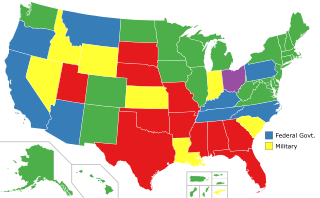

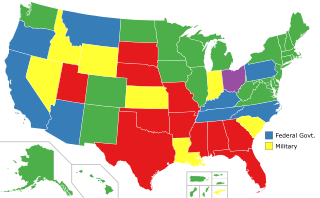

In the United States, capital punishment is a legal penalty throughout the country at the federal level, in 27 states, and in American Samoa. It is also a legal penalty for some military offenses. Capital punishment has been abolished in 23 states and in the federal capital, Washington, D.C. It is usually applied for only the most serious crimes, such as aggravated murder. Although it is a legal penalty in 27 states, 20 states have the ability to execute death sentences, with the other seven, as well as the federal government, being subject to different types of moratoriums.

In the U.S. state of California, capital punishment is not allowed to be carried out as of March 2019, because executions were halted by an official moratorium ordered by Governor Gavin Newsom. Before the moratorium, executions had been frozen by a federal court order since 2006, and the litigation resulting in the court order has been on hold since the promulgation of the moratorium. Thus, there will be a court-ordered moratorium on executions after the termination of Newsom's moratorium if capital punishment remains a legal penalty in California by then.

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States about racial discrimination and United States constitutional criminal procedure. Strauder was the first instance where the Supreme Court reversed a state court decision denying a defendant's motion to remove his criminal trial to federal court pursuant to Section 3 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

In criminal law, the right to counsel means a defendant has a legal right to have the assistance of counsel and, if the defendant cannot afford a lawyer, requires that the government appoint one or pay the defendant's legal expenses. The right to counsel is generally regarded as a constituent of the right to a fair trial. Historically, however, not all countries have always recognized the right to counsel. The right is often included in national constitutions. Of the 194 constitutions currently in force, 153 have language to this effect.

Fortunato Pedro Benavides was an American judge. From 1994 until 2023, he served as a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984), was a landmark Supreme Court case that established the standard for determining when a criminal defendant's Sixth Amendment right to counsel is violated by that counsel's inadequate performance.

Joseph M. Giarratano is a former prisoner who served in Deerfield Correctional Center, in Southampton County, Virginia, US. On November 21, 2017, he was granted parole. He was convicted, based on circumstantial evidence and his own confessions, of murdering Toni Kline and raping and strangling her 15-year-old daughter Michelle on February 4, 1979, in Norfolk, Virginia. He has said that he was an addict for years and had blacked out on alcohol and drugs, waking to find the bodies. He was sentenced to death, and incarcerated on death row for 12 years at the former Virginia State Penitentiary.

District Attorney's Office for the Third Judicial District v. Osborne, 557 U.S. 52 (2009), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court decided that the Constitution's due process clause does not require states to turn over DNA evidence to a party seeking a civil suit under 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

Harbison v. Bell, 556 U.S. 180 (2009), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that held that federal law gave indigent death row inmates the right to federally appointed counsel to represent them in post-conviction state clemency proceedings, when the state has declined to do so. Certiorari was granted by the Supreme Court on June 23, 2008.

The Supreme Court of the United States handed down nineteen per curiam opinions during its 2009 term, which began on October 5, 2009, and concluded October 3, 2010.

Earl Washington Jr. is a former Virginia death-row inmate, who was fully exonerated of murder charges against him in 2000. He had been wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death in 1984 for the 1982 rape and murder of Rebecca Lyn Williams in Culpeper, Virginia. Washington has an IQ estimated at 69, which classifies him as intellectually disabled. He was coerced into confessing to the crime when arrested on an unrelated charge a year later. He narrowly escaped being executed in 1985 and 1994.

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and interpreting law. Although appellate courts have existed for thousands of years, common law countries did not incorporate an affirmative right to appeal into their jurisprudence until the 19th century.

Ryan v. Valencia Gonzales, 568 U.S. 57 (2013), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that a defendant on death row did not need to be held competent during federal habeas corpus proceedings.

In the United States, a public defender is a lawyer appointed by the courts and provided by the state or federal governments to represent and advise those who cannot afford to hire a private attorney. Public defenders are full-time attorneys employed by the state or federal governments. The public defender program is one of several types of criminal legal aid in the United States.

Pasqua v. Council, 892 A.2d 663 was a landmark family court decision decided by the Supreme Court of New Jersey in 2006. The court ruled that indigent parents facing the serious threat of incarceration for nonpayment of child support were entitled to legal counsel.

Bell v. Cone, 535 U.S. 685 (2002), was a Supreme Court of the United States case that upheld a death sentence despite the defendant's argument that he should not be sentenced to death because he was suffering from drug-induced psychosis when he committed the crimes. Cone also argued that he was denied effective assistance of counsel because his attorney failed to present sufficient mitigating evidence during the sentencing phase of his trial and that his attorney inappropriately waived his final argument during the sentencing phase. In an 8–1 opinion written by Chief Justice William Rehnquist, the United States Supreme Court denied Cone's petition for a writ of habeas corpus. The Court held that the actions taken by Cone's attorney during the sentencing phase were "tactical decisions" and that the state courts that denied Cone's appeals did not unreasonably apply clearly established law. Justice John Paul Stevens wrote a dissenting opinion in which he argued that Cone was denied effective assistance of counsel because his attorney failed to "subject the prosecution's case to meaningful adversarial testing."

Cone v. Bell, 556 U.S. 449 (2009), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court held that a defendant was entitled to a hearing to determine whether prosecutors in his 1982 death penalty trial violated his right to due process by withholding exculpatory evidence. The defendant, Gary Cone, filed a petition for postconviction relief from a 1982 death sentence in which he argued that prosecutors violated his rights to due process under the Fourteenth Amendment by withholding police reports and witness statements that potentially could have shown that his drug addiction affected his behavior. In an opinion written by Justice John Paul Stevens, the Supreme Court held that Cone was entitled to a hearing to determine whether the prosecution's failure to disclose exculpatory evidence violated Cone's right to due process; the Court noted that "the quantity and the quality of the suppressed evidence lends support to Cone’s position at trial that he habitually used excessive amounts of drugs, that his addiction affected his behavior during his crime spree". In 2016, Gary Cone died from natural causes while still sitting on Tennessee's death row.

Martinez v. Ryan, 566 U.S. 1 (2012), was a United States Supreme Court case which considered whether criminal defendants ever have a right to the effective assistance of counsel in collateral state post-conviction proceedings. The Court held that a procedural default will not bar a federal habeas court from hearing ineffective-assistance-of-trial-counsel if there was no counsel or ineffective counsel in an initial-review collateral proceeding.

Cullen v. Pinholster, 563 U.S. 170, is a 2011 United States Supreme Court case concerning evidentiary development in federal habeas corpus proceedings. Oral arguments in the case took place on November 9, 2010, and the Supreme Court issued its decision on April 4, 2011. The Supreme Court held 5–4 that only evidence originally presented before the state court in which the claim was originally adjudicated on the merits could be presented when raising a claim under 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(1), and that evidence from a federal habeas court could not be presented in such proceedings. It also held that the convicted murderer Scott Pinholster, the respondent in the case, was not entitled to the habeas relief he had been granted by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.