Let L be a subset of candidates. A solid coalition in support of L is a group of voters who strictly prefer all members of L to all candidates outside of L. In other words, each member of the solid coalition ranks their least-favorite member of L higher than their favorite member outside L. Note that the members of the solid coalition may rank the members of L differently.

The mutual majority criterion says that if there is a solid coalition of voters in support of L, and this solid coalition consists of more than half of all voters, then the winner of the election must belong to L.

Relationships to other criteria

This is similar to but stricter than the majority criterion, where the requirement applies only to the case that L is only one single candidate. It is also stricter than the majority loser criterion, which only applies when L consists of all candidates except one. [2]

All Smith-efficient Condorcet methods pass the mutual majority criterion. [3]

Methods which pass mutual majority but fail the Condorcet criterion may nullify the voting power of voters outside the mutual majority whenever they fail to elect the Condorcet winner.

By method

Anti-plurality voting, range voting, and the Borda count fail the majority-favorite criterion and hence fail the mutual majority criterion. In addition, minimax, the contingent vote, Young's method, first past the post, and Black fail, even though they pass the majority-favorite criterion. [4]

The Schulze method, ranked pairs, instant-runoff voting, Nanson's method, and Bucklin voting pass this criterion.

Borda count

- Majority criterion#Borda count

The mutual majority criterion implies the majority criterion so the Borda count's failure of the latter is also a failure of the mutual majority criterion. The set solely containing candidate A is a set S as described in the definition.

Minimax

Assume four candidates A, B, C, and D with 100 voters and the following preferences:

| 19 voters | 17 voters | 17 voters | 16 voters | 16 voters | 15 voters |

|---|

| 1. C | 1. D | 1. B | 1. D | 1. A | 1. D |

| 2. A | 2. C | 2. C | 2. B | 2. B | 2. A |

| 3. B | 3. A | 3. A | 3. C | 3. C | 3. B |

| 4. D | 4. B | 4. D | 4. A | 4. D | 4. C |

The results would be tabulated as follows:

Pairwise election results | X |

| A | B | C | D |

| Y | A | | [X] 33

[Y] 67 | [X] 69

[Y] 31 | [X] 48

[Y] 52 |

| B | [X] 67

[Y] 33 | | [X] 36

[Y] 64 | [X] 48

[Y] 52 |

| C | [X] 31

[Y] 69 | [X] 64

[Y] 36 | | [X] 48

[Y] 52 |

| D | [X] 52

[Y] 48 | [X] 52

[Y] 48 | [X] 52

[Y] 48 | |

| Pairwise election results (won-tied-lost): | 2-0-1 | 2-0-1 | 2-0-1 | 0-0-3 |

| worst pairwise defeat (winning votes): | 69 | 67 | 64 | 52 |

| worst pairwise defeat (margins): | 38 | 34 | 28 | 4 |

| worst pairwise opposition: | 69 | 67 | 64 | 52 |

- [X] indicates voters who preferred the candidate listed in the column caption to the candidate listed in the row caption

- [Y] indicates voters who preferred the candidate listed in the row caption to the candidate listed in the column caption

Result: Candidates A, B and C each are strictly preferred by more than the half of the voters (52%) over D, so {A, B, C} is a set S as described in the definition and D is a Condorcet loser. Nevertheless, Minimax declares D the winner because its biggest defeat is significantly the smallest compared to the defeats A, B and C caused each other.

Plurality

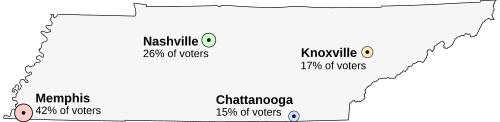

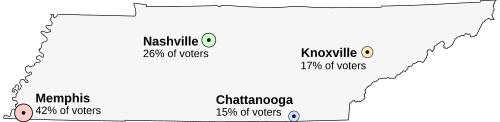

Suppose that Tennessee is holding an election on the location of its capital. The population is concentrated around four major cities. All voters want the capital to be as close to them as possible. The options are:

- Memphis, the largest city, but far from the others (42% of voters)

- Nashville, near the center of the state (26% of voters)

- Chattanooga, somewhat east (15% of voters)

- Knoxville, far to the northeast (17% of voters)

The preferences of each region's voters are:

42% of voters

Far-West | 26% of voters

Center | 15% of voters

Center-East | 17% of voters

Far-East |

|---|

- Memphis

- Nashville

- Chattanooga

- Knoxville

| - Nashville

- Chattanooga

- Knoxville

- Memphis

| - Chattanooga

- Knoxville

- Nashville

- Memphis

| - Knoxville

- Chattanooga

- Nashville

- Memphis

|

58% of the voters prefer Nashville, Chattanooga and Knoxville to Memphis. Therefore, the three eastern cities build a set S as described in the definition. But, since the supporters of the three cities split their votes, Memphis wins under plurality voting.

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.