Apostasy is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that is contrary to one's previous religious beliefs. One who undertakes apostasy is known as an apostate. Undertaking apostasy is called apostatizing. The term apostasy is used by sociologists to mean the renunciation and criticism of, or opposition to, a person's former religion, in a technical sense, with no pejorative connotation.

While freedom of religion is de jure symbolically enshrined in the Malaysian Constitution, it de facto faces many prohibitions and restrictions. A Malay in Malaysia must strictly be a Muslim, and they cannot convert to another religion. Islamic religious practices are determined by official Sharia law, and Muslims can be fined by the state for not fasting or refusing to pray. The country does not consider itself a secular state and that Islam is the state religion of the country, and individuals with no religious affiliation are viewed with hostility.

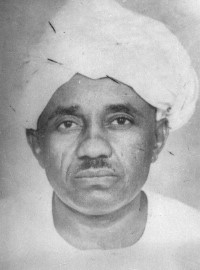

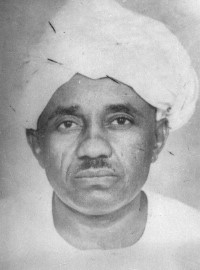

Hassan al-Turabi was a Sudanese politician and scholar. He was the alleged architect of the 1989 Sudanese military coup that overthrew Sadiq al-Mahdi and installed Omar al-Bashir as president. He has been called "one of the most influential figures in modern Sudanese politics" and a "longtime hard-line ideological leader". He was instrumental in institutionalizing Sharia in the northern part of the country and was frequently imprisoned in Sudan, but these "periods of detention" were "interspersed with periods of high political office".

Apostasy in Islam is commonly defined as the abandonment of Islam by a Muslim, in thought, word, or through deed. It includes not only explicit renunciations of the Islamic faith by converting to another religion or abandoning religion, but also blasphemy or heresy by those who consider themselves Muslims, through any action or utterance which implies unbelief, including those who deny a "fundamental tenet or creed" of Islam,. An apostate from Islam is known as a murtadd (مرتدّ).

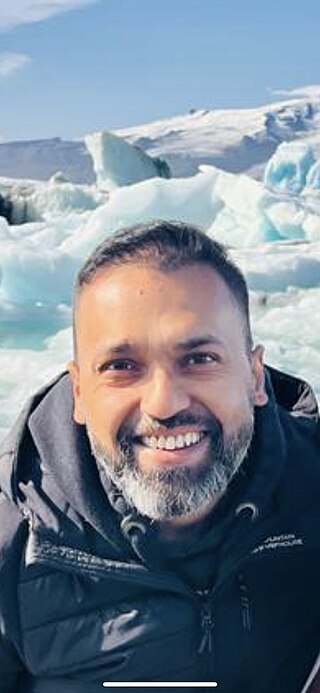

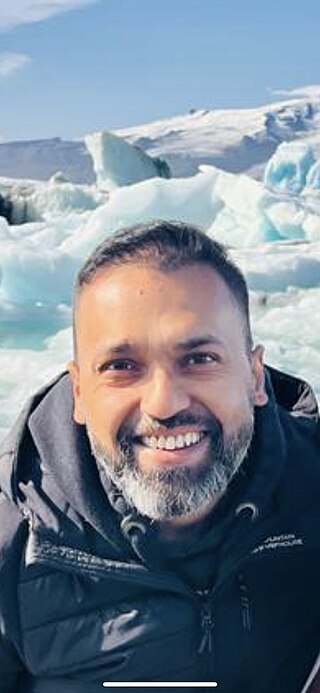

Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na'im is a Sudanese-born Islamic scholar who lives in the United States and teaches at Emory University. He is the Charles Howard Candler Professor of Law at Emory University School of Law, associated professor in the Emory College of Arts and Sciences, and Senior Fellow of the Center for the Study of Law and Religion of Emory University.

The dominant religion in Sudan is Islam practiced by around 90.7% of the nation's population. Christianity is the largest minority faith in country accounting for around 5.4% of the population. A substantial population of the adherents of traditional faiths is also present.

Maryam Namazie is a British-Iranian secularist, communist and human rights activist, commentator, and broadcaster. She is the Spokesperson for Fitnah – Movement for Women’s Liberation, One Law for All and the Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain. She is known for speaking out against Islam and Islamism and defending the right to apostasy and blasphemy.

The Central Council of Ex-Muslims is a German association (Verein) advocating for the rights and interests of non-religious, secular persons of Muslim heritage who have left Islam. It was founded on 21 January 2007 and as of May 2007 had about 200 members, with "hundreds" of membership applications yet to be processed.

The Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain or CEMB is the British branch of the Central Council of Ex-Muslims. It was launched in Westminster on 22 June 2007.

Mahmoud Mohammed Taha, also known as Ustaz Mahmoud Mohammed Taha, was a Sudanese religious thinker, leader, and trained engineer. He developed what he called the "Second Message of Islam", which postulated that the verses of the Qur'an revealed in Medina were appropriate in their time as the basis of Islamic law, (Sharia), but that the verses revealed in Mecca represented the ideal and universal religion, which would be revived when humanity had reached a stage of development capable of implementing them, ushering in a renewed era of Islam based on the principles of freedom and equality. He was executed for apostasy for his religious preaching at the age of 76 by the regime of Gaafar Nimeiry.

The use of politically and religiously-motivated violence dates back to the early history of Islam. Islam has its origins in the behavior, sayings, and rulings of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, his companions, and the first caliphs in the 7th, 8th, and 9th centuries CE. Mainstream Islamic law stipulates detailed regulations for the use of violence, including corporal and capital punishment, as well as regulations on how, when, and whom to wage war against.

Sharia means Islamic law based on age-old concepts. Since the early Islamic states of the eighth and ninth centuries, Sharia always existed alongside other normative systems.

Irreligion in Iran has a long historical background, but is difficult to measure, as those who profess atheism are at risk of arbitrary detention, torture, and the death penalty. Non-religious citizens are officially unrecognized by the Iranian government. In the official 2011 census, 265,899 persons did not state any religion. Between 2017 and 2022, the World Values Survey found that 1.3% of Iranians identified as atheists, and a further 14.3% as not religious. In the 1999-2004 cycle, the WVS had found 1% identified as atheist and 3% as not religious.

Irreligion in the Middle East is the lack of religion in the Middle East. Though atheists in the Middle East are rarely public about their lack of belief, as they are persecuted in many countries where they are classified as terrorists, there are some atheist organizations in the Middle East. Islam dominates public and private life in most Middle East countries. Nonetheless, there reside small numbers of irreligious individuals within those countries who often face serious formal and, in some cases, informal legal and social consequences.

Capital punishment for offenses is allowed by law in some countries. Such offenses include adultery, apostasy, blasphemy, corruption, drug trafficking, espionage, fraud, homosexuality and sodomy, perjury, prostitution, sorcery and witchcraft, theft, and treason.

Among Nonbelievers is a 2015 bilingual English–Dutch documentary on the situation of endangered nonbelievers, especially ex-Muslims, around the world. Set in the United Kingdom, Turkey, the Netherlands and Switzerland, the film is directed by Dorothée Forma and produced by HUMAN with the support of the Dutch Humanist Association. In 2016, it was succeeded by Non-believers: Freethinkers on the Run, which dealt with the fate of apostates and freethinkers in Dutch refugee camps.

Ali Amjad Rizvi is a Pakistani-born Canadian atheist ex-Muslim and secular humanist writer and podcaster who explores the challenges of Muslims who leave their faith. He wrote a column for the Huffington Post and co-hosted the Secular Jihadists for a Muslim Enlightenment podcast together with Armin Navabi.

Ex-Muslims are people who were raised as Muslims or converted to Islam and later left the religion of Islam. Challenges come from the conditions and history of Islam, Islamic culture and jurisprudence, and sometimes local Muslim culture. This has led to increasingly organized literary and social activism by ex-Muslims, and the development of mutual support networks and organizations to meet the challenges of abandoning the beliefs and practices of Islam and to raise awareness of human rights abuses suffered by ex-Muslims.

The situation for apostates from Islam varies markedly between Muslim-minority and Muslim-majority regions. In Muslim-minority countries, "any violence against those who abandon Islam is already illegal". But in some Muslim-majority countries, religious violence is "institutionalised", and "hundreds and thousands of closet apostates" live in fear of violence and are compelled to live lives of "extreme duplicity and mental stress."

In September 1983, Sudanese president Gaafar Nimeiry introduced Islamic Sharia laws in Sudan, known as September Laws, disposing of alcohol and implementing hudud punishments such as public flogging for alcohol consumption and amputations for theft. Nimeiry declared himself the imam of the "Sudanese umma", leading to concerns about the undemocratic implementation of these laws. Hassan al-Turabi assisted with drafting the law and later supported the laws, unlike, the leader of the opposition, Sadiq al-Mahdi's dissenting view.