The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the United States. The movement had its origins in the Reconstruction era during the late 19th century, although it made its largest legislative gains in the 1960s after years of direct actions and grassroots protests. The social movement's major nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience campaigns eventually secured new protections in federal law for the civil rights of all Americans.

Bayard Rustin was an African American leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, nonviolence, and gay rights.

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission is "to bring about equality for all people regardless of race, creed, sex, age, disability, sexual orientation, religion or ethnic background."

Asa Philip Randolph was an American labor unionist and civil rights activist. In 1925, he organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first successful African-American led labor union. In the early Civil Rights Movement and the Labor Movement, Randolph was a prominent voice. His continuous agitation with the support of fellow labor rights activists against racist unfair labor practices, eventually helped lead President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802 in 1941, banning discrimination in the defense industries during World War II. The group then successfully maintained pressure, so that President Harry S. Truman proposed a new Civil Rights Act and issued Executive Orders 9980 and 9981 in 1948, promoting fair employment, anti-discrimination policies in federal government hiring, and ending racial segregation in the armed services.

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, also known as simply the March on Washington or The Great March on Washington, was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rights of African Americans. At the march, final speaker Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial, delivered his historic "I Have a Dream" speech in which he called for an end to racism.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civil rights movement.

The Nashville sit-ins, which lasted from February 13 to May 10, 1960, were part of a protest to end racial segregation at lunch counters in downtown Nashville, Tennessee. The sit-in campaign, coordinated by the Nashville Student Movement and the Nashville Christian Leadership Council, was notable for its early success and its emphasis on disciplined nonviolence. It was part of a broader sit-in movement that spread across the southern United States in the wake of the Greensboro sit-ins in North Carolina.

The Birmingham campaign, also known as the Birmingham movement or Birmingham confrontation, was an American movement organized in early 1963 by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to bring attention to the integration efforts of African Americans in Birmingham, Alabama.

Freedom Schools were temporary, alternative, and free schools for African Americans mostly in the South. They were originally part of a nationwide effort during the Civil Rights Movement to organize African Americans to achieve social, political and economic equality in the United States. The most prominent example of Freedom Schools was in Mississippi during the summer of 1964.

The Journey of Reconciliation, also called "First Freedom Ride", was a form of nonviolent direct action to challenge state segregation laws on interstate buses in the Southern United States. Bayard Rustin and 18 other men and women were the early organizers of the two-week journey that began on April 9, 1947. The participants started their journey in Washington, D.C., traveled as far south as North Carolina, before returning to Washington, D.C.

Clara Shepard Luper was a civic leader, schoolteacher, and pioneering leader in the American Civil Rights Movement. She is best known for her leadership role in the 1958 Oklahoma City sit-in movement, as she, her young son and daughter, and numerous young members of the NAACP Youth Council successfully conducted carefully planned nonviolent sit-in protests of downtown drugstore lunch-counters, which overturned their policies of segregation. The Clara Luper Corridor is a streetscape and civic beautification project from the Oklahoma Capitol area east to northeast Oklahoma City. In 1972, Clara Luper was an Oklahoma candidate for election to the United States Senate. When asked by the press if she, a black woman, could represent white people, she responded: “Of course, I can represent white people, black people, red people, yellow people, brown people, and polka dot people. You see, I have lived long enough to know that people are people.”

The New York City teachers' strike of 1968 was a months-long confrontation between the new community-controlled school board in the largely black Ocean Hill–Brownsville neighborhoods of Brooklyn and New York City's United Federation of Teachers. It began with a one day walkout in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville school district. It escalated to a citywide strike in September of that year, shutting down the public schools for a total of 36 days and increasing racial tensions between Blacks and Jews.

James Peck was an American activist who practiced nonviolent resistance during World War II and in the Civil Rights Movement. He is the only person who participated in both the Journey of Reconciliation (1947) and the first Freedom Ride of 1961, and has been called a white civil rights hero. Peck advocated nonviolent civil disobedience throughout his life, and was arrested more than 60 times between the 1930s and 1980s.

The history of the 1954 to 1968 American civil rights movement has been depicted and documented in film, song, theater, television, and the visual arts. These presentations add to and maintain cultural awareness and understanding of the goals, tactics, and accomplishments of the people who organized and participated in this nonviolent movement.

This is a timeline of the civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for people of color. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally institutionalized racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.

Oretha Castle Haley was an American civil rights activist in New Orleans where she challenged the segregation of facilities and promoted voter registration. She came from a working-class background, yet was able to enroll in the Southern University of New Orleans, SUNO, then a center of student activism. She joined the protest marches and went on to become a prominent activist in the Civil Rights Movement.

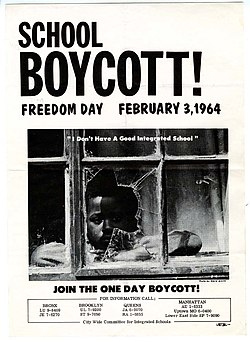

The Chicago Public Schools boycott, also known as Freedom Day, was a mass boycott and demonstration against the segregationist policies of the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) on October 22, 1963. More than 200,000 students stayed out of school, and tens of thousands of Chicagoans joined in a protest that culminated in a march to the office of the Chicago Board of Education. The protest preceded the larger New York City public school boycott, also known as Freedom Day.

Milton Arthur Galamison was a Presbyterian minister who served in Brooklyn, New York. As a community activist, he championed integration and education reform in the New York City public school system, and organized two school boycotts.

The Chester school protests were a series of demonstrations that occurred from November 1963 through April 1964 in Chester, Pennsylvania. The demonstrations focused on ending the de facto segregation that resulted in the racial categorization of Chester public schools, even after the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka (1954). The racial unrest and civil rights protests were led by Stanley Branche of the Committee for Freedom Now (CFFN) and George Raymond of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Persons (NAACP).

The Committee for Freedom Now (CFFN) was an American civil rights organization in Chester, Pennsylvania, that worked to end de facto segregation and improve the conditions at predominantly black schools in Chester. CFFN was founded in 1963 by Stanley Branche along with the Swarthmore College chapter of Students for a Democratic Society and Chester parents. From November 1963 to April 1964, CFFN and the Chester chapter of the NAACP, led by George Raymond, initiated the Chester school protests which made Chester a key battleground in the civil rights movement.