Related Research Articles

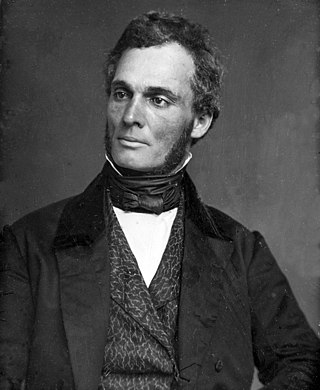

William Lloyd Garrison was an American abolitionist, journalist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read anti-slavery newspaper The Liberator, which Garrison founded in 1831 and published in Boston until slavery in the United States was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865.

The American Anti-Slavery Society was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, had become a prominent abolitionist and was a key leader of this society, who often spoke at its meetings. William Wells Brown, also a freedman, also often spoke at meetings. By 1838, the society had 1,350 local chapters with around 250,000 members.

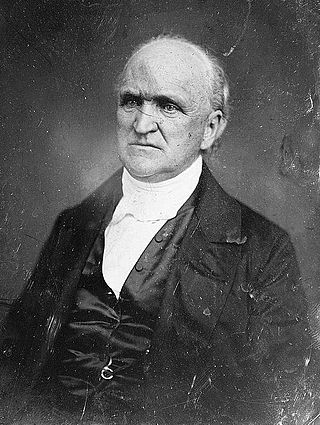

Arthur Tappan was an American businessman, philanthropist and abolitionist. He was the brother of Ohio Senator Benjamin Tappan and abolitionist Lewis Tappan, and nephew of Harvard Divinity School theologian Rev. Dr. David Tappan.

Henry Highland Garnet was an American abolitionist, minister, educator and orator. Having escaped as a child from slavery in Maryland with his family, he grew up in New York City. He was educated at the African Free School and other institutions, and became an advocate of militant abolitionism. He became a minister and based his drive for abolitionism in religion.

Robert Purvis was an American abolitionist in the United States. He was born in Charleston, South Carolina, and was likely educated at Amherst Academy, a secondary school in Amherst, Massachusetts. He spent most of his life in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In 1833 he helped found the American Anti-Slavery Society and the Library Company of Colored People. From 1845 to 1850 he served as president of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and also traveled to Britain to gain support for the movement.

Theodore Sedgwick Wright (1797–1847), sometimes Theodore Sedgewick Wright, was an African-American abolitionist and minister who was active in New York City, where he led the First Colored Presbyterian Church as its second pastor. He was the first African American to attend Princeton Theological Seminary, from which he graduated in 1828 or 1829. In 1833 he became a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, an interracial group that included Samuel Cornish, a Black Presbyterian, and many Congregationalists, and served on its executive committee until 1840.

Elijah Parish Lovejoy was an American Presbyterian minister, journalist, newspaper editor, and abolitionist. After his murder by a mob, he became a martyr to the abolitionist cause opposing slavery in the United States. He was also hailed as a defender of free speech and freedom of the press.

Lane Seminary, sometimes called Cincinnati Lane Seminary, and later renamed Lane Theological Seminary, was a Presbyterian theological college that operated from 1829 to 1932 in Walnut Hills, Ohio, today a neighborhood in Cincinnati. Its campus was bounded by today's Gilbert, Yale, Park, and Chapel Streets.

Samuel Hanson Cox was an American Presbyterian minister and a leading abolitionist.

George Washington Dixon was an American singer, stage actor, and newspaper editor. He rose to prominence as a blackface performer after performing "Coal Black Rose", "Zip Coon", and similar songs. He later turned to a career in journalism, during which he earned the enmity of members of the upper class for his frequent allegations against them.

The Bowery Theatre was a playhouse on the Bowery in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, New York City. Although it was founded by rich families to compete with the upscale Park Theatre, the Bowery saw its most successful period under the populist, pro-American management of Thomas Hamblin in the 1830s and 1840s. By the 1850s, the theatre came to cater to immigrant groups such as the Irish, Germans, and Chinese. It burned down four times in 17 years, a fire in 1929 destroying it for good. Although the theatre's name changed several times, it was generally referred to as the "Bowery Theatre".

Thomas Souness Hamblin was an English actor and theatre manager. He first took the stage in England, then immigrated to the United States in 1825. He received critical acclaim there, and eventually entered theatre management. During his tenure at New York City's Bowery Theatre he helped establish working-class theatre as a distinct form. His policies preferred American actors and playwrights to British ones, making him an important influence in the development of early American drama.

The Chatham Garden Theatre or Chatham Theatre was a playhouse in the Chatham Gardens of New York City. It was located on the north side of Chatham Street on Park Row between Pearl and Duane streets in lower Manhattan. The grounds ran through to Augustus Street. The Chatham Garden Theatre was the first major competition to the high-class Park Theatre, though in its later years it sank to the bottom of New York's stratified theatrical order, below even the Bowery Theatre.

Lewis Tappan was a New York abolitionist who worked to achieve freedom for the enslaved Africans aboard the Amistad. He was born in Northampton, Massachusetts, into a Calvinist household.

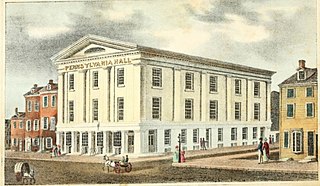

Pennsylvania Hall, "one of the most commodious and splendid buildings in the city," was an abolitionist venue in Philadelphia, built in 1837–38. It was a "Temple of Free Discussion", where antislavery, women's rights, and other reform lecturers could be heard. Four days after it opened it was destroyed by arson, the work of an anti-abolitionist mob.

The Emancipator (1833–1850) was an American abolitionist newspaper, at first published in New York City and later in Boston. It was founded as the official newspaper of the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS). From 1840 to 1850, it was published by the Liberty Party; the publication changed names several times as it merged with other abolitionist newspapers in Boston.

The Cincinnati riots of 1836 were caused by racial tensions at a time when African Americans, some of whom had escaped from slavery in the Southern United States, were competing with whites for jobs. The racial riots occurred in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States in April and July 1836 by a mob of whites against black residents. These were part of a pattern of violence at that time. A severe riot had occurred in 1829, led by ethnic Irish, and another riot against blacks broke out in 1841. After the Cincinnati riots of 1829, in which many African Americans lost their homes and property, a growing number of whites, such as the "Lane rebels" who withdrew from the Cincinnati Lane Seminary en masse in 1834 over the issue of abolition, became sympathetic to their plight. The anti-abolitionist rioters of 1836, worried about their jobs if they had to compete with more blacks, attacked both the blacks and white supporters.

The Mother African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, also known as "Mother Zion", located at 140–148 West 137th Street between Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard and Lenox Avenue in the Harlem neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City, is the oldest African-American church in New York City, and the "mother church" of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion conference.

In the United States, abolitionism, the movement that sought to end slavery in the country, was active from the late colonial era until the American Civil War, the end of which brought about the abolition of American slavery for non-criminals through the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

A symbolic day in the history of the American abolitionist movement was May 14, 1838. On that date two related events occurred: the inauguration in Philadelphia of Pennsylvania Hall, built to symbolize and facilitate the abolitionist movement, and the wedding of Theodore Weld and Angelina Grimké, "the wedding that ignited Philadelphia." The wedding was held that day because of the many out-of-town abolitionists present for the inauguration of the Hall.

References

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace, Gotham: a history of New York City to 1898, (Oxford University Press) 1999.

- Cockrell, Dale (1997). Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and Their World. Cambridge University Press.

- Headley, Joel Tyler. Great Riots of New York 1712 to 1873... (New York, 1873)

- Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, Oxford University Press, 1993, ISBN 0-19-509641-X. pp. 131–134

- Wilmeth, Don B., and Bigsby, C. W. E. (1998) The Cambridge History of American Theatre: Beginnings to 1870. New York: Cambridge University Press.