Related Research Articles

Dracula is a novel by Bram Stoker, published in 1897. An epistolary novel, the narrative is related through letters, diary entries, and newspaper articles. It has no single protagonist and opens with solicitor Jonathan Harker taking a business trip to stay at the castle of a Transylvanian nobleman, Count Dracula. Harker escapes the castle after discovering that Dracula is a vampire, and the Count moves to England and plagues the seaside town of Whitby. A small group, led by Abraham Van Helsing, investigate, hunt and kill Dracula.

Transylvania is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains and to the west the Apuseni Mountains. Broader definitions of Transylvania also include the western and northwestern Romanian regions of Crișana and Maramureș, and occasionally Banat. Historical Transylvania also includes small parts of neighbouring Western Moldavia and even a small part of south-western neighbouring Bukovina to its north east. The capital of the region is Cluj-Napoca.

The undead are beings in mythology, legend, or fiction that are deceased but behave as if alive. Most commonly the term refers to corporeal forms of formerly alive humans, such as mummies, vampires, and zombies, which have been reanimated by supernatural means, technology, or disease. In some cases, the term also includes incorporeal forms of the dead, such as ghosts.

A vampire is a mythical creature that subsists by feeding on the vital essence of the living. In European folklore, vampires are undead creatures that often visited loved ones and caused mischief or deaths in the neighbourhoods which they inhabited while they were alive. They wore shrouds and were often described as bloated and of ruddy or dark countenance, markedly different from today's gaunt, pale vampire which dates from the early 19th century. Vampiric entities have been recorded in cultures around the world; the term vampire was popularized in Western Europe after reports of an 18th-century mass hysteria of a pre-existing folk belief in Southeastern and Eastern Europe that in some cases resulted in corpses being staked and people being accused of vampirism. Local variants in Southeastern Europe were also known by different names, such as shtriga in Albania, vrykolakas in Greece and strigoi in Romania, cognate to Italian 'Strega', meaning Witch.

Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror is a 1922 silent German Expressionist vampire film directed by F. W. Murnau and starring Max Schreck as Count Orlok, a vampire who preys on the wife of his estate agent and brings the plague to their town.

Strigoi in Romanian mythology are troubled spirits that are said to have risen from the grave. They are attributed with the abilities to transform into an animal, become invisible, and to gain vitality from the blood of their victims. Bram Stoker's Dracula has become the modern interpretation of the Strigoi through their historic links with vampirism.

Largely as a result of the success of Bram Stoker's Dracula, Transylvania has become a popular setting for gothic horror fiction, and most particularly vampire fiction. In some later books and movies Stoker's Count Dracula was conflated with the historical Vlad III Dracula, known as Vlad the Impaler (1431–1476), who though most likely born in the Transylvanian city of Sighișoara, ruled over neighboring Wallachia.

Wilhelmina "Mina" Harker is a fictional character and the main female character in Bram Stoker's 1897 Gothic horror novel Dracula.

The Scholomance was a fabled school of black magic in Romania, especially in the region of Transylvania. It was run by the Devil, according to folkloric accounts. The school enrolled about ten students to become the Solomonari. Courses taught included the speech of animals and magic spells. One of the graduates was chosen by the Devil to be the Weathermaker and tasked with riding a dragon to control the weather.

Nosferatu the Vampyre is a 1979 horror film written and directed by Werner Herzog. It is set primarily in 19th-century Wismar, Germany and Transylvania, and was conceived as a stylistic remake of F. W. Murnau's 1922 German Dracula adaptation Nosferatu. The picture stars Klaus Kinski as Count Dracula, Isabelle Adjani as Lucy Harker, Bruno Ganz as Jonathan Harker, and French artist-writer Roland Topor as Renfield. There are two different versions of the film, one in which the actors speak English, and one in which they speak German.

A moroi is a type of vampire or ghost in Romanian folklore. A female moroi is called a moroaică. In some versions, a moroi is a phantom of a dead person which leaves the grave to draw energy from the living.

Jonathan Harker is a fictional character and one of the main protagonists of Bram Stoker's 1897 Gothic horror novel Dracula. An English solicitor, his journey to Transylvania and encounter with the vampire Count Dracula and his Brides at Castle Dracula constitutes the dramatic opening scenes in the novel and most of the film adaptations.

The Solomonar or Șolomonar is a wizard believed in Romanian folklore to ride a dragon and control the weather, causing rain, thunder, or hailstorm.

(Jane) Emily Gerard was a Scottish 19th-century author best known for the influence her collections of Transylvanian folklore had on Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula.

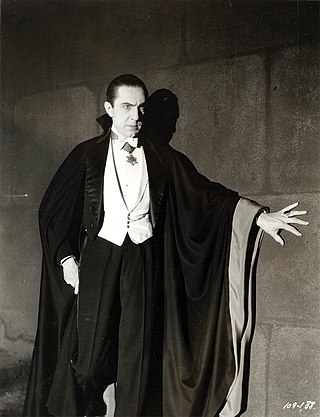

Count Dracula is the title character of Bram Stoker's 1897 gothic horror novel Dracula. He is considered the prototypical and archetypal vampire in subsequent works of fiction. Aspects of the character are believed by some to have been inspired by the 15th-century Wallachian prince Vlad the Impaler, who was also known as Vlad Dracula, and by Sir Henry Irving, an actor for whom Stoker was a personal assistant.

The character of Count Dracula from the 1897 novel Dracula by Bram Stoker, has remained popular over the years, and many forms of media have adopted the character in various forms. In their book Dracula in Visual Media, authors John Edgar Browning and Caroline Joan S. Picart declared that no other horror character or vampire has been emulated more times than Count Dracula. Most variations of Dracula across film, comics, television and documentaries predominantly explore the character of Dracula as he was first portrayed in film, with only a few adapting Stoker's original narrative more closely. These including borrowing the look of Count Dracula in both the Universal's series of Dracula and Hammer's series of Dracula, including include the characters clothing, mannerisms, physical features hair style and his motivations such as wanting to be in a home away from Europe.

David John Skal is an American historian, critic, writer, and on-camera commentator known for his research and analysis of horror films, horror history and horror culture.

Elizabeth Russell Miller was a Professor Emerita at Memorial University of Newfoundland. She resided in Toronto. In her early academic career, she focused on Newfoundland literature, primarily the life and work of her father, well-known Newfoundland author and humorist Ted Russell. Beginning in 1990, her major field of research was Bram Stoker's novel Dracula, its author, sources and influence. She published several books on the subject, including Reflections on Dracula, Dracula: Sense & Nonsense, a volume on Dracula for the Dictionary of Literary Biography and, most recently, Bram Stoker's Notes for Dracula: A Facsimile Edition with Robert Eighteen-Bisang. She founded the Dracula Research Centre and was the founding editor of the Journal of Dracula Studies now at Kutztown University of Pennsylvania.

The Lord Ruthven Award is an annual award presented by the Lord Ruthven Assembly, a group of academic scholars specialising in vampire literature and affiliated with the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts (IAFA).

Robert Eighteen-Bisang was a Canadian author and scholar who was one of the world's foremost authorities on vampire literature and mythology.

References

Citations

- ↑ Wilhelm Schmidt (1865), "Das Jahr und seine Tage in Meinung und Brauch der Rumänen Siebenbürgens", Österreichische Revue, 3(1):211–226.

- 1 2 3 Gerard, Emily (July 1885). "Transylvanian Superstitions". The Nineteenth Century : 128–144.

- ↑ Gerard, Emily (1888). The Land Beyond the Forest: Facts, Figures, and Fancies from Transylvania. Harper & Brothers.

- ↑ Wolf, Leonard (1997). Dracula: The Connoisseur's Guide. Random House.

- ↑ Hogg, Anthony (2011). "Unearthing Nosferau", Diary of an Amateur Vampirologist, 28 February. Accessed 28 March 2011. The article in question is Wilhelm Schmidt, "Das Jahr und seine Tage in Meinung und Brauch der Rumänen Siebenbürgens", Österreichische Revue, 3(1):211–226.

- ↑ Perhaps referring to the use of the nosferatu to excuse illegitimate pregnancies and infidelity, as discussed in detail by Wlislocki (see below)

- ↑ German : Hieran reihe ich den Vampyr – nosferatu. Es ist dies die uneheliche Frucht zweier unehelich Gezeugter oder der unselige Geist eines durch Vampyre Getödteten, der als Hund, Katze, Kröte, Frosch, Laus, Floh, Wanze, kurz in jeder Gestalt erscheinen kann und wie der altslavische und böhmische Blkodlak, Vukodlak oder polnischen Mora und russische Kikimora als Incubus oder Succubus – zburatorul – namentlich bei Neuverlobten sein böses Wesen treibt. Was hierüber vor mehr als hundert Jahren geglaubt und zur Abwehr geübt wurde, ist noch heute wahr, und es dürfte kaum ein Dorf geben, welches nich im Stande ware Selbsterlebtes oder doch Gehörtes mit der festen Ueberzeugung der Wahrheit vorzubringen.

- ↑ Schmidt, Wilhelm (1866). Das Jahr und seine Tage in Meinung und Brauch der Rumänen Siebenbürgens: Ein Beitrag zur Kenntniss d. Volksmythus (in German). Hermannstadt, Austria-Hungary: A. Schmiedicke. p. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 Skal, David J. (2004) [1990]. Hollywood Gothic: The Tangled Web Of Dracula From Novel To Stage To Screen (Revised ed.). Norton. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-0-571-21158-6.

- ↑ "For all that die from the preying of the Un-dead become themselves Un-dead, and prey on their kind. And so the circle goes on ever widening, like as the ripples from a stone thrown in the water. Friend Arthur, if you had met that kiss which you know of before poor Lucy die, or again, last night when you open your arms to her, you would in time, when you had died, have become nosferatu, as they call it in Eastern Europe, and would for all time make more of those Un-Deads that so have filled us with horror." (Stoker 1897). This seems to be the motivation for Leonard Wolf to gloss nosferatu as "not dead." (Stoker, Wolf 1975)

- ↑ Haining, Peter (2000). A Dictionary of Vampires. Robert Hale. pp. 184–185. ISBN 978-0-7090-6550-0.

- ↑ von Wlislocki, Heinrich (1896). "Quälgeister im Volksglauben der Rumänen". Am Ur-Quell. 6: 108–109.

- ↑ Hogg, Anthony (2010). "Examining Roumanian Superstitions." Diary of an Amateur Vampirologist, August 22. Accessed 28 March 2011.

- 1 2 Stoker, Bram (2006) [1897]. Paul Moliken (ed.). Dracula (Literary Touchstone ed.). Prestwick House. p. 349. ISBN 978-1-58049-382-6.

- 1 2 Melton, J. Gordon (1999). the Vampire Book: The Encyclopedia of the Undead . Visible Ink Press. pp. 496–497. ISBN 978-1-57859-071-1.

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George; Robert Scott; Henry Stuart Jones (1940) [1843]. A Greek-English Lexicon (9th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-864226-8.

- ↑ Buican, Denis (1991). Dracula et ses Avatars: de Vlad l'Empaleur à Staline et Ceausescu. Editions de l'Espace Européen. p. 96. ISBN 978-2-7388-0131-9.

- ↑ Dunn-Mascetti, Manuela (1992). Vampire: the Complete Guide to the World of the Undead. Penguin. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-14-023801-3.

- ↑ Boboc, Anamaria (2011). Dracula: de la Gotic la Postmodernism. Iasi. p. 8.

General bibliography

- Boboc, Anamaria (2011). Dracula: de la Gotic la Postmodernism (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). Iași, Romania: Lumen. p. 8. ISBN 978-973-166-279-4.

- Buican, Denis (1991). Dracula et ses Avatars: de Vlad l'Empaleur à Staline et Ceausescu (in French). Editions de l'Espace Européen. p. 96. ISBN 978-2-7388-0131-9. (As a native Romanian, Dr. Buican's opinion that nosferatu is a mishearing of necuratu carries particular weight.)

- Dunn-Mascetti, Manuela (1992). Vampire: the Complete Guide to the World of the Undead. Penguin. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-14-023801-3.

- Gerard, Emily (July 1885). "Transylvanian Superstitions". The Nineteenth Century : 128–144.

- Gerard, Emily (1888). The Land Beyond the Forest: Facts, Figures, and Fancies from Transylvania. Harper & Brothers.

- Haining, Peter (2000). A Dictionary of Vampires. Robert Hale and Company. pp. 184–185. ISBN 978-0-7090-6550-0.

- Liddell, Henry George; Robert Scott; Henry Stuart Jones (1940) [1843]. A Greek-English Lexicon (9th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-864226-8.

- "Magyar néprajzi lexikon" (in Hungarian). Retrieved 2007-02-22. ("Hungarian Ethnographic Lexicon")

- Melton, J. Gordon (1999). the Vampire Book: The Encyclopedia of the Undead . Visible Ink Press. pp. 496–497. ISBN 978-1-57859-071-1.

- Schmidt, Wilhelm (1865). "Das Jahr und seine Tage in Meinung und Brauch der Rumänen Siebenbürgens". Österreichische Revue (in German). 3 (1): 211–226.

- Skal, David J. (2004) [1990]. Hollywood Gothic: The Tangled Web Of Dracula From Novel To Stage To Screen (Revised ed.). Norton. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-0-571-21158-6. (Skal reprints a large quotation of the relevant Wlislocki material)

- Skal, David J. (1996) [1996]. V Is for Vampire: The A-Z Guide to Everything Undead (Original ed.). Plume. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-452-27173-9.

- Stoker, Bram (1897). Dracula. Archibald Constable and Company.

- Stoker, Bram (2006) [1897]. Paul Moliken (ed.). Dracula (Literary Touchstone ed.). Prestwick House. p. 349. ISBN 978-1-58049-382-6.

- Stoker, Bram (1975) [1897]. Leonard Wolf (ed.). The Annotated Dracula. Crown. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-517-52017-8.

- von Wlislocki, Heinrich (1896). "Quälgeister im Volksglauben der Rumänen". Am Ur-Quell (in German). 6: 108–109.

- Wolf, Leonard (1997). Dracula: The Connoisseur's Guide. Random House. (The information relating to the "Nosferatu" from the article written by Mrs. Gerard in 1885 is reprinted on pp. 21–22).