The Nyamakala, or Nyamakalaw, are the historic occupational castes among Sudano-Sahelian societies of West Africa, particularly among the Mandinka people. [1] [2] The Nyamakala are known as Nyaxamalo among the Soninke people, [1] [3] and Nyenyo among the Wolof people. [4] They are found throughout the Sahel region, from Mali and Senegal to Chad and several other parts of the West African region historically known as the "Western Sudan". [5]

Contents

The term Nyamakala originally applied to any talented people, but as slavery, social differentiation and stratification increased with Islamic religious violence called jihads, and later the colonial rule, their status fell to a lowly level below the nobles and free people. [1] Nyama in the traditional Mandinka society implies "vital force", while Kala connotes "handle". Thus, any type of occupation that handled the vital force of nature, was a Nyamakala. [1] In its historic contexts, stated Charles Bird, Martha Kendall and Kalilou Tera, Nyama has accumulated different meanings. In one, it connotes notions of "evil or satanic force, dangerous, polluting, energizing, imperfect self control" and in others it is "morally neutral or energizing". In yet another context, Nyama implies "refuse, garbage". [6] With the arrival of Muslims, the evil or polluting contexts became their focus, while the caste people themselves preferred the neutral or energizing connotations. [7]

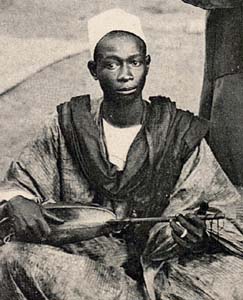

Among Mandinka, the Nyamakala occupational castes included Jeli or Jeliyu (musicians, griots), Numu (carpenters, smiths), Garanke (leather workers, weavers) and Fune or Finah (singers specializing in Islamic praise). [1] The specific castes had different terms in other ethnic groups of West Africa. For example, among the Soninke people, the griots were called Gesere, the smiths Tage and the carpenter caste was called Sake. [1]

The Nyamakala have been endogamous, occupation inheriting castes. [8] [9] [10] Among the Mande people such as the Mandinke, Soninke and others, Nyamakala caste people have been despised and considered of lowly status, in some regions as Jon (slave) and Wolosa (descendant of slave). [11] [12]

Some scholars such as Vaughn stated that while Nyamakala have been castes of West Africa, it does not necessarily imply a generic and uniform "caste system" because the social stratification in Africa was very complex with the inclusion of slaves, race and religious elements. [13] [14] Others consider Nyamakala as a part of a caste system, while acknowledging that there were regional variations. [15] [16] [17]