Related Research Articles

The economy of Malawi is $7.522 billion by gross domestic product as of 2019, and is predominantly agricultural, with about 80% of the population living in rural areas. The landlocked country in south central Africa ranks among the world's least developed countries. In 2017, agriculture accounted for about one-third of GDP and about 80% of export revenue. The economy depends on substantial inflows of economic assistance from the IMF, the World Bank, and individual donor nations. The government faces strong challenges: to spur exports, to improve educational and health facilities, to face up to environmental problems of deforestation and erosion, and to deal with the problem of HIV/AIDS in Africa. Malawi is a least developed country according to United Nations.

Nyasaland was a British protectorate located in Africa that was established in 1907 when the former British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. Between 1953 and 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. After the Federation was dissolved, Nyasaland became independent from Britain on 6 July 1964 and was renamed Malawi.

The British Central Africa Protectorate (BCA) was a British protectorate proclaimed in 1889 and ratified in 1891 that occupied the same area as present-day Malawi: it was renamed Nyasaland in 1907. British interest in the area arose from visits made by David Livingstone from 1858 onward during his exploration of the Zambezi area. This encouraged missionary activity that started in the 1860s, undertaken by the Universities' Mission to Central Africa, the Church of Scotland and the Free Church of Scotland, and which was followed by a small number of settlers. The Portuguese government attempted to claim much of the area in which the missionaries and settlers operated, but this was disputed by the British government. To forestall a Portuguese expedition claiming effective occupation, a protectorate was proclaimed, first over the south of this area, then over the whole of it in 1889. After negotiations with the Portuguese and German governments on its boundaries, the protectorate was formally ratified by the British government in May 1891.

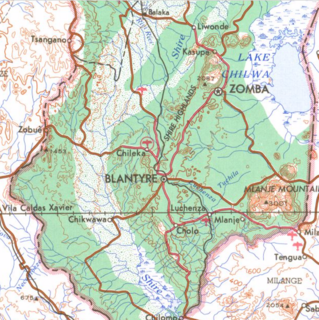

The Shire Highlands are a plateau in southern Malawi, located east of the Shire River. It is a major agricultural area and the most densely populated part of the country.

Thangata is a word deriving from the Chewa language of Malawi which has changed its meaning several times, although all meanings relate to agriculture. Its original, pre-colonial usage related to reciprocal help given in neighbours' fields or freely-given agricultural labour as thanks for a benefit. In colonial times, between 1891 and 1962, it generally meant agricultural labour given in lieu of a cash rent, and generally without any payment, by a tenant on an estate owned by a European. Thangata was often exploited, and tenants could be forced to work on the owners' crops for four to six months annually when they could have cultivated their own crops. From the 1920s, the name thangata was extended to situations where tenants were given seeds to grow set quotas of designated crops instead of providing cash or labour. Both forms of thangata were abolished in 1962, but both before and after independence and up to the present, the term has been used for short-term rural casual work, often on tobacco estates, which is considered by workers to be exploitative.

Malawi is one of the world's least developed countries and is ranked 170 out of 187 countries according to the 2010 Human Development Index. It has about 16 million people, 53% of whom live under the national poverty line, and 90% of whom live on less than $2 per day. The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) estimated that there are 46,000 severely malnourished children.

The main economic products of Malawi are tobacco, tea, cotton, groundnuts, sugar and coffee. These have been among the main cash crops for the last century, but tobacco has become increasingly predominant in the last quarter-century, with a production in 2011 of 175,000 tonnes. Over the last century, tea and groundnuts have increased in relative importance while cotton has decreased. The main food crops are maize, cassava, sweet potatoes, sorghum, bananas, rice, and Irish potatoes and cattle, sheep and goats are raised. The main industries deal with agricultural processing of tobacco, tea and sugar and timber products. The industrial production growth rate is estimated at 10% (2009).

Tobacco production in Malawi is one of the nation's largest sources of income. As of 2005, Malawi was the twelfth-largest producer of tobacco leaves and the 7th largest global supporter of tobacco leaves. As of 2010, Malawi was the world's leading producer of burley leaf tobacco. With the decline of tobacco farms in the West, interest in Malawi's low-grade, high-nicotine tobacco has increased. Today, Malawian tobacco is found in blends of nearly every cigarette smoked in industrialized nations including the popular and ubiquitous Camel and Marlboro brands. It is the world's most tobacco dependent economy. In 2013 Malawi produced about 133,000 tonnes of tobacco leaf, a reduction from a maximum of 208,000 tonnes in 2009 and although annual production was maintained at similar levels in 2014 and 2015, prices fell steadily from 2013 to 2017, in part because of weakening world demand but also because of declining quality.

A. L. Bruce Estates was one of three largest owners of agricultural estates in colonial Nyasaland. Alexander Low Bruce, the son-in-law of David Livingstone, acquired a large estate at Magomero in the Shire Highlands of Nyasaland in 1893, together with two smaller ones. On his death, these estates were to operate as a trust to bring Christianity and Commerce to Central Africa. However his two sons later formed a commercial company which bought the estates from the trust. The company gained a reputation for the harsh exploitation and ill-treatment of its tenants under a labour system known by the African term "thangata", which operated in the plantation cultivation of cotton and tobacco. This exploitation was one of the causes of the 1915 uprising led by John Chilembwe, which resulted in the deaths of three of the company's European employees. After the failure of its own cotton and tobacco plantations, the company forced its tenants to grow tobacco rather than food on their own land and significantly underpaid them. Following almost three decades of losses, the Magomero estate was in poor condition, but the company was able to sell it at a profit between 1949 and 1952 because the government needed land for resettlement of African former tenants evicted from private estates. The company was liquidated in 1959.

The Natives on Private Estates Ordinance, 1928 was a colonial ordinance passed by the Legislative Council of the Nyasaland Protectorate. The body was composed mainly of senior colonial officials, with a minority of nominated members, to represent European residents. The ordinance regulated the conditions under which land could be farmed by African tenants on estates owned by European settlers within that protectorate. The legislation corrected some of the worst abuses of the system of thangata under which tenants were required to work for the estate owner in lieu of paying rent.

Eugene Charles Albert Sharrer was a British subject by naturalisation but of German descent, who was a leading entrepreneur in what is now Malawi for around fifteen years between his arrival in 1888 and his departure. He rapidly built-up commercial operations including wholesale and retail trading, considerable holdings of land, cotton and coffee plantations and a fleet of steamers on the Zambezi and Shire rivers. Sharrer was prominent in pressure groups that represented the interests of European planters and their businesses to the colonial authorities, and was responsible for the development of the first railway in what had become the British Central Africa Protectorate, whose construction was agreed in 1902. In 1902, Sharrer consolidate all his business interests into the British Central Africa Company Ltd and became its principal shareholder Shortly after this he left British Central Africa permanently for London, although he retained his financial interests in the territory. Very little is known of his history before he arrived in Central Africa but he died in London during the First World War.

Blantyre and East Africa Ltd is a company that was incorporated in Scotland in 1898 and is still in existence. Its main activity was the ownership of estates in the south of what is now Malawi. The main estate crops it grew were tobacco until the 1950s and tea, which it continued to grow until the company’s tea estates were sold. Blantyre and East Africa Ltd was one of four large estate-owning companies in colonial Nyasaland which together owned over 3.4 million acres of land, including the majority of the fertile land in the Shire Highlands. The company acquired most of its landholdings between 1898 and 1901 from several early European settlers, whose title to this land had been recognised by Certificates of Claim issued by the administration of the British Central Africa Protectorate. After the boom for Europeans growing tobacco ended in about 1927, the company retained one large estate in Zomba District where its tenants were encouraged to grow tobacco and others where it grew tea. It was also left with a scattering of small estates that it neither operated nor effectively managed but obtained cash rents from African tenants on crowded and unsupervised estates. Many of its estates, excluding the tea estates which it continued to manage directly, were sold to the colonial administration of Nyasaland between 1950 and 1955.

The British Central Africa Company Ltd was one of the four largest European-owned companies that operated in colonial Nyasaland, now Malawi. The company was incorporated in 1902 to acquire the business interests that Eugene Sharrer, an early settler and entrepreneur, had developed in the British Central Africa Protectorate. Sharrer became the majority shareholder of the company on its foundation. The company initially had trading and transport interests, but these were sold by the 1930s. For most of the colonial period, its extensive estates produced cotton, tobacco or tea but the British Central Africa Company Ltd developed the reputation of being a harsh and exploitative landlord whose relations with its tenants were poor. In 1962, shortly before independence, the company sold most of its undeveloped land to the Nyasaland government, but it retained some plantations and two tea factories. It changed its name to The Central Africa Company Ltd and was acquired by the Lonrho group, both in 1964.

The Abrahams Commission was a commission appointed by the Nyasaland government in 1946 to inquire into land issues in Nyasaland. This followed riots and disturbances by tenants on European-owned estates in Blantyre and Cholo districts in 1943 and 1945. The commission had only one member, Sir Sidney Abrahams, a Privy Counsellor and lawyer, the former Attorney General of the Gold Coast, Zanzibar and Uganda, and the former Chief Justice, first of Uganda and then Ceylon. There had been previous reviews to consider the uneven distribution of land between Africans and European, the shortage of land for subsistence farming and the position of tenants on private estates. These included the Jackson Land Commission in 1920, the Ormsby-Gore Commission on East Africa in 1924 and, most recently, the Bell Commission on the Financial Position and Development of Nyasaland in 1938, but none of these had provided a permanent solution. Abrahams proposed that the Nyasaland government should purchase all unused or under-utilised freehold land on European-owned estates, which would then become Crown land, available to African farmers. The Africans on estates were to be offered the choice of remaining on their current estate as paid workers or tenants, or of moving to Crown land. These proposals were not implemented in full until 1952. The report of the Abrahams Commission divided opinion. Africans were generally in favour of its proposals, as were both the governors in post from 1942 to 1947, Edmund Richards, and the incoming governor, Geoffrey Colby. Estate owners and managers were strongly against it, and many European settlers bitterly attacked it.

John Buchanan (1855–1896), was a Scottish horticulturist who went to Central Africa, now Malawi, in 1876 as a lay member of the missionary party that established Blantyre Mission. Buchanan came to Central Africa as an ambitious artisan: his character was described as dour and devout but also as restlessly ambitious, and he saw in Central Africa a gateway to personal achievement. He started a mission farm on the site of Zomba, Malawi but was dismissed from the mission in 1881 for brutality. From being a disgraced missionary, Buchanan first became a very influential planter owning, with his brothers, extensive estates in Zomba District. He then achieved the highest position he could in the British administration as Acting British Consul to Central Africa from 1887 to 1891. In that capacity declared a protectorate over the Shire Highlands in 1889 to pre-empt a Portuguese expedition that intended to claim sovereignty over that region. In 1891, the Shire Highlands became part of the British Central Africa Protectorate. John Buchanan died at Chinde in Mozambique in March 1896 on his way to visit Scotland, and his estates were later acquired by the Blantyre and East Africa Ltd.

The Agricultural Development and Marketing Corporation, usually known as ADMARC, was formed in Malawi in 1971 as a Government-owned corporation or parastatal to promote the Malawian economy by increasing the volume and quality of its agricultural exports, to develop new foreign markets for the consumption of Malawian agricultural produce and to support Malawi's farmers. it was the successor of a number of separate marketing boards of the colonial-era and early post-colonial times, whose functions were as much about controlling African smallholders or generating government revenues as in promoting agricultural development. At its foundation, ADMARC was given the power to finance the economic development of any public or private organisation, agricultural or not.

The Native Tobacco Board, or NTB, was formed in Nyasaland in 1926 as a Government-sponsored body with the primary aim of controlling the production of tobacco by African smallholders and generating revenues for the government, and the secondary aim of increasing the volume and quality of tobacco exports. At the time of its formation, much of Nyasaland's tobacco was produced on European-owned estates, whose owners demanded protection against African tobacco production that might compete with their own, and against the possibility that profitable smallholder farming would draw cheap African labour away from their estates. From around 1940, the aim of the NTB was less about restricting African tobacco production and more about generating governmental revenues, supposedly for development but still involving the diversion of resources away from smallholder farming. In 1956, the activities, powers and duties of what had by then been renamed the African Tobacco Board were transferred to the Agricultural Production and Marketing Board, which had powers to buy smallholder surpluses of tobacco, maize, cotton and other crops, but whose producer prices continued to be biased against peasant producers.

Cotton in Malawi is an important part of the agricultural history of Malawi. Cotton is not indigenous to the country, but was introduced into warmer lowland areas no later than the 17th century. Production in the late pre-colonial and early colonial period was limited but, from the early 20th century, it has been grown mainly by African smallholders in the south of the country. For a brief period during the First World War, cotton was the most valuable export crop, and it has remained an important earner of foreign exchange.

Leroy Vail whose birth name was Hazen Leroy Vail was an American specialist in African studies and educator who specialized in the history and linguistics of Central Africa and later extended his interests to Southern Africa. He taught in universities in Malawi, Zambia and the United States and his research in the first two countries inclined him toward the view that Central Africa underwent a period of underdevelopment that began in the mid-19th century and accelerated under colonial rule. After his return to the United States, he cooperated with Landeg White on studies of colonial Mozambique and on the value of African poetry and songs as a source of oral history.

Richard Wildman Kettlewell, (1910–1994), was a colonial agricultural officer who spent all his colonial career in Nyasaland apart from three years of wartime army service. He became Director of Agriculture in 1951 and Secretary for National Resources then Minister of Lands and Surveys between 1960 and 1962. He was influential in the late colonial administration of Nyasaland, and responsible for the introduction of several controversial agricultural and land-use policies that were highly unpopular with African farmers and which he accepted had promoted nationalist sentiments in the protectorate. After leaving Nyasaland in 1962 shortly before its independence, he settled in the Cotswolds for the remainder of his life and undertook part-time consulting work on tropical land use.

References

- ↑ Vaughan (1987).

- ↑ Kettlewell (1965).

- ↑ Vail (1975).

- ↑ Vaughan (1987).

- ↑ McCracken (2012), p. 13.

- ↑ McCann (2005), p. 8.

- ↑ McCracken (2012), p. 14.

- ↑ McCann (2005), p. 8.

- ↑ Miller (1964), pp. 124, 134-5.

- ↑ McCann (2005), pp. 15-16.

- ↑ Hulme (1996), p.9

- ↑ Rasmusson (1987), p. 10.

- ↑ Nyasaland Protectorate (1955) p. 6.

- ↑ Mwakasungura (1986), p. 43.

- ↑ Bishop (1995), pp. 59-61.

- ↑ McCracken (2012), p. 14.

- ↑ Woods (1993), pp. 141-3.

- ↑ Pike (1969), pp. 196-9.

- ↑ Vaughan (1987), p. 71.

- ↑ Kandaŵire (1977), p. 188.

- ↑ Iliffe, (1985) p. 276.

- ↑ McCracken (1985), pp. 43-4.

- ↑ Vaughan (1987), pp. 92-3, 95.

- ↑ Jayne, Jones and others (1987), p. 217.

- ↑ Vaughan (1987), pp. 96-7.

- ↑ Jayne, Jones and others (1987), p. 217.

- ↑ Thompson and Woodfall (1956), p. 138.

- ↑ Morris (2016), pp. 92, 95, 130-1.

- ↑ Morris (2016), p. 217.

- ↑ Vaughan (1992), pp. 81-3.

- ↑ Vaughan (1992), p. 72.

- ↑ Rasmusson (1987), p. 10.

- ↑ Morris (2016), p. 276.

- ↑ Morris (2016), p. 276.

- ↑ Vaughan (1987), pp. 27-9.

- ↑ Vaughan (1992), pp. 73-4.

- ↑ Baker (1994), p. 185.

- ↑ Baker (1994), p. 191.

- ↑ Morris (2016), p. 277-8.

- ↑ Vaughan (1992), p. 75.

- ↑ Vaughan (1992), pp. 76-7.

- ↑ Vaughan (1992), pp. 78-9.

- ↑ Vaughan (1992), p. 80.

- ↑ Iliffe, (1985) p. 264.

- ↑ Morris (2016), p. 277.

- ↑ Vaughan (1992), pp. 79-81.

- ↑ Vaughan (1992), p. 81.

- ↑ Vaughan (1992), pp. 83-4.

- ↑ Vaughan (1992), pp. 84-5.

- ↑ Iliffe, (1990) pp. 97, 100,103.

- ↑ Thompson and Woodfall (1956), p. 139.

- ↑ Baker (1994), pp. 181, 194.

- ↑ Baker (1994), pp. 65, 194.

- ↑ Baker (1994), pp. 192-4.

- ↑ Baker (1994), pp. 194, 196, 204-5.

- ↑ Vaughan (1987), pp. 64-6.

- ↑ Nyasaland Government (1946), Annexe p. 90.

- ↑ Jayne, Jones and others (1987), p. 217.

- ↑ White (1987), p. 209.

- ↑ Baker (1994), pp. 234-41.

- ↑ Baker (1994), p. 113.

- ↑ McCracken (2012), pp. 248-9.

- ↑ McCracken (2012), p. 250.

- ↑ McCracken (2012), pp. 250, 318-9.

- ↑ Kettlewell 1965, pp. 239-41, 243-5, 247.

- ↑ Bishop (1995), pp 61-2, 67-8.

- ↑ Snapp (1998), pp. 2572-88.

- ↑ Vaughan (1987), pp. 60-1, 64-9.

- ↑ Snapp (1998), pp. 2572-88.

- ↑ Vaughan (1987), p. 78.

- ↑ Pike (1968), p. 197.

- ↑ Farringdon (1975). pp. 69-71, 82

- ↑ White (1987), p. 195.

- ↑ White (1987), pp. 203-4.

- ↑ White (1987), pp. 206-8.

- ↑ Vail (1975), p. 89.

- ↑ Mandala (2006), pp. 505.

- ↑ Baker (1975), pp. 56-8.

- ↑ Vail (1975), pp. 103-4, 112.

- ↑ Mandala (2006), pp. 519-20.

- ↑ Vail (1975), pp. 104, 108-9.

- ↑ Irvine (1959), pp. 181-2.

- ↑ Nyasaland Protectorate (1946), pp. 39, 66-7.

- ↑ Sen (1981), p. 165.

- ↑ Vaughan (1991), p. 355.

- ↑ Green (2011), p. 269-70.

- ↑ Vaughan (1992), p. 34.

- ↑ Vaughan (1992), p. 86.

- ↑ Vaughan (1987), pp. 65-6, 110-12, 127-9.

- ↑ Vaughan (1991), pp. 355-6.

- ↑ Sen (1981), pp. 7, 154-6.

- ↑ Sen (1981), pp. 164-6.

- ↑ Vaughan (1987), pp. 104-6.

- ↑ Cromwell and Zambezi (1974), p.16.

- ↑ Vaughan (1992), pp. 115-16.

- ↑ Smale and Heisey (1997), p.65.

- ↑ Malawi Government (2002), pp 46, 63.

- ↑ Tiba (2005), pp 69-70.

- ↑ Conroy (2006), pp. 123, 125.

- ↑ Young (2000), pp. 243-4.