Related Research Articles

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have used malevolent magic against their own community, and often to have communed with evil beings. It was thought witchcraft could be thwarted by protective magic or counter-magic, which could be provided by cunning folk or folk healers. Suspected witches were also intimidated, banished, attacked or killed. Often they would be formally prosecuted and punished, if found guilty or simply believed to be guilty. European witch-hunts and witch trials in the early modern period led to tens of thousands of executions. In some regions, many of those accused of witchcraft were folk healers or midwives. European belief in witchcraft gradually dwindled during and after the Age of Enlightenment.

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. The classical period of witch-hunts in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America took place in the Early Modern period or about 1450 to 1750, spanning the upheavals of the Reformation and the Thirty Years' War, resulting in an estimated 35,000 to 50,000 executions. The last executions of people convicted as witches in Europe took place in the 18th century. In other regions, like Africa and Asia, contemporary witch-hunts have been reported from sub-Saharan Africa and Papua New Guinea, and official legislation against witchcraft is still found in Saudi Arabia and Cameroon today.

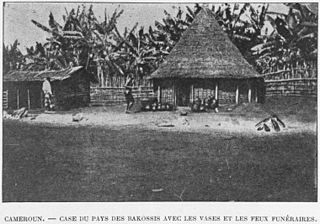

The Bakweri are a Bantu ethnic group of the Republic of Cameroon. They are closely related to Cameroon's coastal peoples, particularly the Duala and Isubu.

Efik mythology consists of a collection of myths narrated, sung or written down by the Efik people and passed down from generation to generation. Sources of Efik mythology include bardic poetry, art, songs, oral tradition and proverbs. Stories concerning Efik myths include creation myths, supernatural beings, mythical creatures, and warriors. Efik myths were initially told by Efik people and narrated under the moonlight. Myths, legends and historical stories are known in Efik as Mbụk while moonlight plays in Efik are known as Mbre Ọffiọñ.

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Thirty people were found guilty, 19 of whom were executed by hanging. One other man, Giles Corey, was pressed to death after refusing to enter a plea, and at least five people died in jail.

Abong-Mbang is a town and commune in the East Region of Cameroon. Abong-Mbang is located at a crossroads of National Route 10 and the road that leads south to Lomié. Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon, is 178 km to the west, and Bertoua, the capital of the East Province, lies 108 km to the east. From Ayos, at the border in the Centre Province 145 km (90 mi) from Abong-Mbang, the tar on National Route 10 ends and a dirt road begins. Abong-Mbang is the seat of the Abong-Mbang sub-division and the Haut-Nyong division. The town is headed by a mayor. Gustave Mouamossé has held the post since August 2002. Abong-Mbang is site of one of the East Province's four Courts of First Instance and a prefectural prison. The population was estimated at 18,700 in 2001.

A jengu is a water spirit in the traditional beliefs of the Sawabantu groups of Cameroon, like the Duala, Bakweri, Malimba, Subu, Bakoko, Oroko people. Among the Bakweri, the term used is liengu. Miengu are similar to bisimbi in the Bakongo spirituality and Mami Wata. The Bakoko people use the term Bisima.

Young King William, born Ngombe or Ngomb' a Bila, was, as William II of Bimbia, the chief and king of Bimbia on the coast of Cameroon and of the Isubu ethnic group who lived there. Young King William inherited a kingdom where power was shifting from the monarchy to wealthy traders, a situation that only grew worse under William II's impotent rule. As competition for European trade among the coastal peoples of Cameroon grew more intense, young King William's rivals multiplied and his centralised authority crumbled. He was murdered in 1882.

Ewale a Mbedi was the eponymous ancestor of the Duala people of Cameroon. According to the oral histories of the Duala and related Sawa peoples of the Cameroon coast, Ewale hailed from a place called Piti. He and his followers migrated southwest to the coast and settled at the present-day location of Douala. The area was inhabited by the Bassa and/or Bakoko, who were driven inland by the new arrivals. Meanwhile, Ewale and his followers set up trade with European merchant ships.

Mbedi a Mbongo is the common ancestor of many of the Sawa coastal ethnic groups of Cameroon according to their oral traditions. Stories say that he lived at a place called Piti, northeast of present-day Douala. From there, his sons migrated south toward the coast in what are known as the Mbedine events. These movements may be mythical in many cases, but anthropologists and historians accept the plausibility of a migration of some Sawa ancestors to the coast during the 16th century.

Social cleansing is social group-based killing that consists of the elimination of members of society who are considered "undesirable", including, but not limited to, the homeless, criminals, street children, the elderly, the disabled. This phenomenon is caused by a combination of economic and social factors, but killings are notably present in regions with high levels of poverty and disparities of wealth. Perpetrators are usually of the same community as the victims and they are often motivated by the idea that the victims are a drain on the resources of society. Efforts by national and local governments to stop these killings have been largely ineffective. The government and police forces are often involved in the killings, especially in South America.

Edwin Ardener (1927–1987) was a British social anthropologist and academic. He was also noted for his contributions to the study of history. Within anthropology, some of his most important contributions were to the study of gender, as in his 1975 work in which he described women as "muted" in social discourse.

Mount Kupe or Mont Koupé is a plutonic mountain in the Western High Plateau of Cameroon, part of the Cameroon line of volcanoes. It is the highest of the Bakossi mountains, rising to 2,064 metres (6,772 ft).

The Bakossi people are a Bantu ethnic group that live on the western and eastern slopes of Mount Mwanenguba and Mount Kupe in the Bakossi Mountains of Cameroon. They number about 200,000, mostly engaged in subsistence farming but also producing some coffee and cocoa.

The Mungo River is a large river in Cameroon that drains the mountains in the southern portion of the Cameroon line of active and extinct volcanoes.

Jantzen & Thormählen was a German firm based in Hamburg that was established to exploit the resources of Cameroon. The firm's commercial and political influence was a major factor in the establishment of the colony of Kamerun in 1884.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, "the practice of ritual killing and human sacrifice continues to take place ... in contravention of the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights and other human rights instruments." In the 21st century, such practices have been reported in Nigeria, Uganda, Swaziland, Liberia, Tanzania, Namibia, and Zimbabwe, as well as Mozambique, and Mali.

Witch-hunts are practiced today throughout the world. While prevalent world-wide, hot-spots of current witch-hunting are India, Papua New Guinea, Amazonia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Body counts of modern witch-hunts exceed those of early-modern witch-hunting.

Witchcraft among the Zande people of North Central Africa is magic used to inflict harm on an individual that is native to the Azande tribal peoples. The belief in witchcraft is present in every aspect of Zande society. They believe it is a power that can only be passed on from a parent to their child. To the Azande, a witch uses witchcraft when he has hatred towards another person. Witchcraft can also manipulate nature to bring harm upon the victim of the witch. Oracles and witch doctors determine whether someone is guilty of using witchcraft on another villager. More magic is then created to avenge the victim and punish the one who committed the transgression.

Shirley G. Ardener is a pioneer of research on women and a committed anthropological researcher working with Bakweri people in Cameroon since the 1950s, initially with her husband Edwin Ardener (1927–1987).

References

- 1 2 3 4 Geschiere, Peter (December 1998). "Witchcraft as an Issue in the "Politics of Belonging": Democratization and Urban Migrants' Involvement with the Home Village". African Studies Review. African Studies Association. 41 (3): 61–91. doi:10.2307/525354. JSTOR 525354. S2CID 144012600.

- ↑ Geschiere, Peter (1997). The Modernity of Witchcraft: Politics and the Occult in Postcolonial Africa. University of Virginia Press. p. 151. ISBN 0813917034.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bongmba, Elias Kifon (16 May 2001). African Witchcraft and Otherness: A Philosophical and Theological Critique of Intersubjective Relations. Suny Press. ISBN 9780791449899.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ardener, Edwin (1996). Kingdom on Mount Cameroon: Studies in the History of the Cameroon Coast, 1500-1970. Berghahn Series. Vol. 1. Berghahn Books. pp. 249–252. ISBN 1571819290.

- ↑ van Alphen, Ernst (2003). Africa and Its Significant Others: Forty Years of Intercultural Entanglement. Thamyris intersecting. Vol. 11. Rodopi. pp. 90–95. ISBN 9042010290.