Alexander Mackenzie was a Canadian politician who served as the second prime minister of Canada, in office from 1873 to 1878.

Sir John Alexander Macdonald was the first prime minister of Canada, serving from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 to 1891. He was the dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, and had a political career that spanned almost half a century.

The Pacific Scandal was a political scandal in Canada involving large sums of money being paid by private interests to the Conservative government to cover election expenses in the 1872 Canadian federal election, to influence the bidding for a national rail contract. As part of British Columbia's 1871 agreement to join the Canadian Confederation, the federal government had agreed to build a transcontinental railway linking the seaboard of British Columbia to the eastern provinces.

Canadian Confederation was the process by which three British North American provinces—the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick—were united into one federation called the Dominion of Canada, on July 1, 1867. Upon Confederation, Canada consisted of four provinces: Ontario and Quebec, which had been split out from the Province of Canada, and the provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Over the years since Confederation, Canada has seen numerous territorial changes and expansions, resulting in the current number of ten provinces and three territories.

James W. Cockburn was a Canadian Conservative politician, and a father of Canadian Confederation.

Events from the year 1873 in Canada.

The Conservative Party of Canada has gone by a variety of names over the years since Canadian Confederation. Initially known as the "Liberal-Conservative Party", it dropped "Liberal" from its name in 1873, although many of its candidates continued to use this name.

The 1867 Canadian federal election was held from August 7 to September 20, 1867, and was the first election for the new country of Canada. It was held to elect members representing electoral districts in the provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario and Quebec to the House of Commons of the 1st Canadian Parliament. The provinces of Manitoba (1870) and British Columbia (1871) were created during the term of the 1st Parliament of Canada and were not part of this election.

The Liberal-Conservative Party was the formal name of the Conservative Party of Canada until 1873, and again from 1922 to 1938, although some Conservative candidates continued to run under the label as late as the 1911 election and others ran as simple Conservatives before 1873. In many of Canada's early elections, there were both "Liberal-Conservative" and "Conservative" candidates; however, these were simply different labels used by candidates of the same party. Both were part of Sir John A. Macdonald's government and official Conservative and Liberal-Conservative candidates would not, generally, run against each other. It was also common for a candidate to run on one label in one election and the other in a subsequent election.

Peter Mitchell was a Canadian politician and one of the Fathers of Confederation.

The 1874 Canadian federal election was held on January 22, 1874, to elect members of the House of Commons of Canada of the 3rd Parliament of Canada. Sir John A. Macdonald, who had recently been forced out of office as prime minister, and his Conservatives were defeated by the Liberal Party under their new leader Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie.

Joseph-Goderic (Joseph-Godric) Blanchet, was a Canadian physician and politician. He was the only person to serve as both Speaker of the House of Commons of Canada and Speaker of a provincial legislature. He represented Lévis in the House of Commons of Canada as a Liberal-Conservative member from 1867 to 1873 and from 1879 to 1883; he represented Bellechasse from 1875 to 1878. He also represented Lévis in the Legislative Assembly of Quebec from 1867 to 1875.

Sir Antoine-Aimé Dorion was a French Canadian politician and jurist.

Disallowance and reservation are historical constitutional powers that were instituted in several territories throughout the British Empire as a mechanism to delay or overrule legislation. Originally created to preserve the Crown's authority over colonial governments, these powers are now generally considered politically obsolete, and in many cases have been formally abolished.

Charles Dewey Day, was a lawyer, judge and political figure in Lower Canada and Canada East. He was a member of the Special Council of Lower Canada, which governed Lower Canada after the Lower Canada Rebellions in 1837 and 1838. He was elected to the first Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada in 1841, but resigned in 1842 to accept an appointment to the Court of Queen's Bench of Lower Canada.

Post-Confederation Canada (1867–1914) is history of Canada from the formation of the Dominion to the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Canada had a population of 3.5 million, residing in the large expanse from Cape Breton to just beyond the Great Lakes, usually within a hundred miles or so of the Canada–United States border. One in three Canadians was French, and about 100,000 were aboriginal. It was a rural country composed of small farms. With a population of 115,000, Montreal was the largest city, followed by Toronto and Quebec at about 60,000. Pigs roamed the muddy streets of Ottawa, the small new national capital.

Peter McLaren was a Canadian politician and Senator from Ontario. McLaren was the Plaintiff in McLaren v Caldwell, that resulted in the landmark decision of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council that upheld provincial jurisdiction in matters of a local or private nature, as well as over property and civil rights.

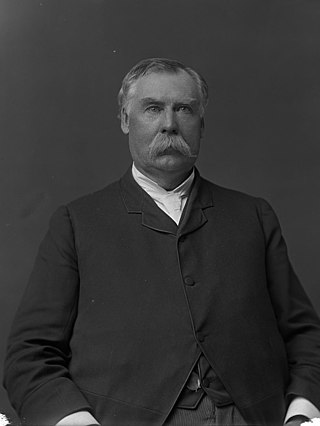

This article is the Electoral history of Sir John A. Macdonald, the first Prime Minister of Canada.

The Electoral Franchise Act, 1885 was a federal statute that regulated elections in Canada for a brief period in the late 19th century. The act was in force from 1885, when it was passed by John A. Macdonald's Conservative majority; to 1898, when Wilfrid Laurier's Liberals repealed it. The Electoral Franchise Act restricted the vote to propertied men over 21. It excluded women, Indigenous people west of Ontario, and those designated "Chinese" or "Mongolian".

Disallowance and reservation are historical constitutional powers in Canada that act as a mechanism to delay or overrule legislation passed by Parliament or a provincial legislature. In contemporary Canadian history, disallowance is an authority granted to the governor general in council to invalidate an act passed by a provincial legislature. Reservation is an authority granted to the lieutenant governor to withhold royal assent from a bill which has been passed by a provincial legislature; the bill is then "reserved" for consideration by the federal cabinet.