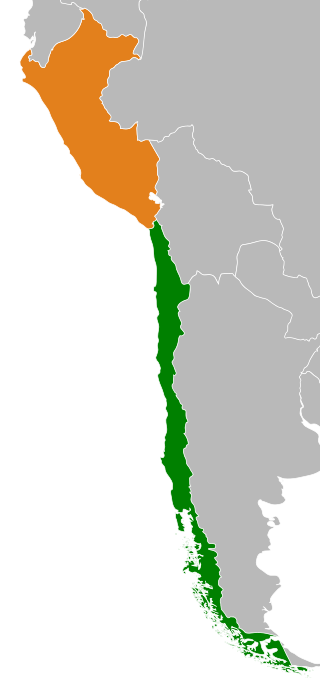

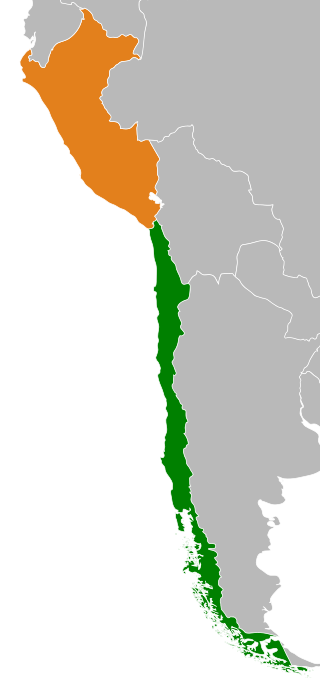

The geography of Chile is extremely diverse as the country extends from a latitude of 17° South to Cape Horn at 56° and from the ocean on the west to Andes on the east. Chile is situated in southern South America, bordering the South Pacific Ocean and a small part of the South Atlantic Ocean. Chile's territorial shape is among the world's most unusual. From north to south, Chile extends 4,270 km (2,653 mi), and yet it only averages 177 km (110 mi) east to west. Chile reaches from the middle of South America's west coast straight down to the southern tip of the continent, where it curves slightly eastward. Diego Ramírez Islands and Cape Horn, the southernmost points in the Americas, where the Pacific and Atlantic oceans meet, are Chilean territory. Chile's northern neighbors are Peru and Bolivia, and its border with Argentina to the east, at 5,150 km (3,200 mi), is the world's third-longest. The total land size is 756,102 km2 (291,933 sq mi). The very long coastline of 6,435 km (3,999 mi) gives it the 11th largest exclusive economic zone of 3,648,532 km2 (1,408,706 sq mi).

Bolivia traditionally has maintained normal diplomatic relations with all hemispheric states except Chile. Foreign relations are handled by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, headed by the Chancellor of Bolivia, Rogelio Mayta.

A landlocked country is a country that does not have territory connected to an ocean or whose coastlines lie on endorheic basins. There are currently 44 landlocked countries and 4 landlocked de facto states. Kazakhstan is the world's largest landlocked country while Ethiopia is the world’s most populous landlocked country.

The Atacama Desert border dispute is a dispute between Chile and Bolivia that stems from the transfer of the Bolivian Coast and the southern tip of Peru to Chile in the 19th century through the Treaty of Ancón with Peru and the Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1904 between Chile and Bolivia after the War of the Pacific (1879–1883). The dispute is considered to be ongoing because Bolivia still claims a sovereign access to the Pacific Ocean. The conflict takes its name from the Atacama Desert on which lies the disputed territory. Due to a transfer of land to both Argentina and Chile during the Chilean annexation of the Bolivian coast in 1879, the Puna de Atacama dispute—this spin-off dispute was settled in 1899.

The Arica y Parinacota Region is one of Chile's 16 first order administrative divisions. It comprises two provinces, Arica and Parinacota. It borders Peru's Department of Tacna to the north, Bolivia's La Paz and Oruro departments to the east and Chile's Tarapacá Region to the south. Arica y Parinacota is the 5th smallest, the 3rd least populous and the 6th least densely populated of the regions of Chile. Arica is the region's capital and largest city.

The Bolivian Navy is a branch of the Armed Forces of Bolivia. As of 2008, the Bolivian Navy had approximately 5,000 personnel. Although Bolivia has been landlocked since the War of the Pacific and its 1904 peace treaty, Bolivia established a River and Lake Force in January 1963 under the Ministry of National Defense. It consisted of four boats supplied from the United States and 1,800 personnel recruited largely from the Bolivian Army. The Bolivian Navy was renamed the Bolivian Naval Force in January 1966, but it has since been called the Bolivian Navy as well. It became a separate branch of the armed forces in 1963. Bolivia has large rivers which are tributaries to the Amazon which are patrolled to prevent smuggling and drug trafficking. Bolivia also maintains a naval presence on Lake Titicaca, the highest navigable lake in the world, which the country shares with Peru.

International law is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for states across a broad range of domains, including war, diplomacy, economic relations, and human rights. Scholars distinguish between international legal institutions on the basis of their obligations, precision, and delegation.

Peru v Chile is a public international law case concerning a territorial dispute between the South American republics of Peru and Chile over the sovereignty of an area at sea in the Pacific Ocean approximately 37,900 square kilometres (14,600 sq mi) in size. Peru contended that its maritime boundary delimitation with Chile was not fixed, but Chile claimed that it holds no outstanding border issues with Peru. On January 16, 2008, Peru brought forth the case to the International Court of Justice at The Hague, the Netherlands, which accepted the case and formally filed it as the Case concerning maritime delimitation between the Republic of Peru and the Republic of Chile - Perú v. Chile.

Chilean-Peruvian relations refers to the historical and current bilateral relationship between the adjoining South American countries of the Republic of Chile and the Republic of Peru. Peru and Chile have shared diplomatic relations since at least the time of the Inca Empire in the 15th century. Under the Viceroyalty of Peru, Chile and Peru had connections using their modern names for the first time. Chile aided in the Peruvian War of Independence by providing troops and naval support.

International relations between the Republic of Chile and the Plurinational State of Bolivia have been strained ever since independence in the early 19th century because of the Atacama border dispute. Relations soured even more after Bolivia lost its coast to Chile during the War of the Pacific and became a landlocked country. Chile and Bolivia have maintained only consular relations since 1978, when territorial negotiations failed and Bolivia decided to sever diplomatic relations with Chile. However, in spite of straining relationship, Chile and Bolivia still have economic treaties supporting tourism and cooperation; therefore, trading between two nations is not affected by the territorial dispute.

Arica was a historical province of Peru, which existed between 1823 and 1883. It was populated by pre-Hispanic peoples for a long period of time before Spanish colonisation in the early 16th century saw the transformation of a small town into a thriving port. Trade in both gold and silver was facilitated through Arica after the precious metals were first extracted from the Potosí silver mines of Bolivia. Following the War of the Pacific, the province was transferred to Chile and became an official Chilean territory in 1929.

The Department of the Litoral, also known as the Atacama Department and commonly known as the Bolivian coast, was the description of the extent of the Pacific coast of the Atacama Desert included in the territory of Bolivia from its inception in 1825 until 1879, when it was lost to Chile.

The Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1904 between Chile and Bolivia was signed in Santiago de Chile on October 20, 1904, to delineate the boundary through 96 specified points between Cerro Zapaleri and Cerro Chipe and to regulate the relations between the two countries 20 years after the end of the War of the Pacific.

The Chilean occupation of Peru began on November 2, 1879, with the beginning of the Tarapacá campaign during the War of the Pacific. The Chilean Army successfully defeated the Peruvian Army and occupied the southern Peruvian territories of Tarapacá, Arica and Tacna. By January 1881, the Chilean army had reached Lima, and on January 17 of the same year, the occupation of Lima began.

Bolivia–Peru relations refers to the current and historical relationship between Bolivia and Peru. Both nations are members of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, Group of 77, Organization of American States, Organization of Ibero-American States and the United Nations.

The consequences of the War of the Pacific were profound and numerous in the countries involved.

The Arica Department was a territorial division of Chile that existed between 1884 and 1929. It was ceded by the Treaty of Ancón in 1883 and placed under military administration, and then created on the 31st of October 1884, as one of the three departments of the Tacna Province, and was returned to Peru at midnight on the 28th of August 1929, under the terms agreed upon in the Treaty of Lima of the same year.

The Charaña Accord, also known as the Hug of Charaña or the Act of Charaña, is the name given to an unrealized treaty that was discussed between the dictators of Bolivia and Chile, Hugo Banzer and Augusto Pinochet respectively. These discussions took place mostly on the Bolivian train station of Charaña on February 8, 1975, and included the brief reestablishment of diplomatic relations between the two nations which had been severed on 1962 because of the Atacama border dispute which was to be solved via a Chilean proposal for the exchange of territories between Bolivia and Chile, with the former receiving a corridor to the Pacific Ocean which would provide it with access to the sea and Chile receiving an equivalent amount of territory from Bolivia along its border with Chile.

Dispute over the Status and Use of the Waters of the Silala is a case at the International Court of Justice. In the case, Chile petitioned the Court to declare the Silala River an "international watercourse whose use by Chile and Bolivia is governed by customary international law." Chile presented the case in 2016 while the Bolivian case against Chile, Obligation to Negotiate Access to the Pacific Ocean, was still ongoing. According to France 24 the case came as a surprise.

The Chilean–Peruvian territorial dispute is a territorial dispute between Chile and Peru that started in the aftermath of the War of the Pacific and ended significantly in 1929 with the signing of the Treaty of Lima and in 2014 with a ruling by the International Court of Justice. The dispute applies since 2014 to a 37,610 km2 territory in the Chile–Peru border, as a result of the maritime dispute between both states.