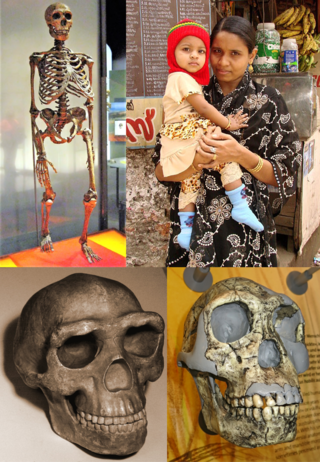

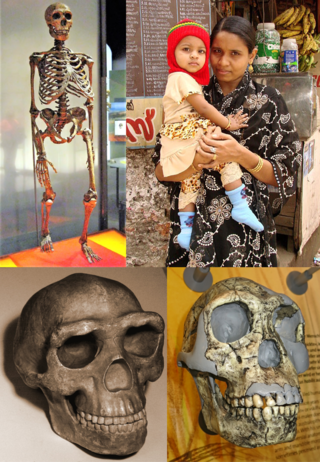

Early modern human (EMH), or anatomically modern human (AMH), are terms used to distinguish Homo sapiens that are anatomically consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans, from extinct archaic human species. This distinction is useful especially for times and regions where anatomically modern and archaic humans co-existed, for example, in Paleolithic Europe. Among the oldest known remains of Homo sapiens are those found at the Omo-Kibish I archaeological site in south-western Ethiopia, dating to about 233,000 to 196,000 years ago, the Florisbad site in South Africa, dating to about 259,000 years ago, and the Jebel Irhoud site in Morocco, dated about 315,000 years ago.

Cro-Magnon is an Aurignacian site, located in a rock shelter at Les Eyzies, a hamlet in the commune of Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil, Dordogne, southwestern France.

Homo heidelbergensis is an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human which existed during the Middle Pleistocene. It was subsumed as a subspecies of H. erectus in 1950 as H. e. heidelbergensis, but towards the end of the century, it was more widely classified as its own species. It is debated whether or not to constrain H. heidelbergensis to only Europe or to also include African and Asian specimens, and this is further confounded by the type specimen being a jawbone, because jawbones feature few diagnostic traits and are generally missing among Middle Pleistocene specimens. Thus, it is debated if some of these specimens could be split off into their own species or a subspecies of H. erectus. Because the classification is so disputed, the Middle Pleistocene is often called the "muddle in the middle".

Herto Man refers to human remains discovered in 1997 from the Upper Herto member of the Bouri Formation in the Afar Triangle, Ethiopia. The remains have been dated as between 154,000 and 160,000 years old. The discovery of Herto Man was especially significant at the time, falling within a long gap in the fossil record between 300 and 100 thousand years ago and representing the oldest dated H. sapiens remains then described.

Solo Man is a subspecies of H. erectus that lived along the Solo River in Java, Indonesia, about 117,000 to 108,000 years ago in the Late Pleistocene. This population is the last known record of the species. It is known from 14 skullcaps, two tibiae, and a piece of the pelvis excavated near the village of Ngandong, and possibly three skulls from Sambungmacan and a skull from Ngawi depending on classification. The Ngandong site was first excavated from 1931 to 1933 under the direction of Willem Frederik Florus Oppenoorth, Carel ter Haar, and Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald, but further study was set back by the Great Depression, World War II and the Indonesian War of Independence. In accordance with historical race concepts, Indonesian H. erectus subspecies were originally classified as the direct ancestors of Aboriginal Australians, but Solo Man is now thought to have no living descendants because the remains far predate modern human immigration into the area, which began roughly 55,000 to 50,000 years ago.

Homo is a genus of great ape that emerged from the genus Australopithecus and encompasses only a single extant species, Homo sapiens, along with a number of extinct species classified as either ancestral or closely related to modern humans; these include Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis. The oldest member of the genus is Homo habilis, with records of just over 2 million years ago. Homo, together with the genus Paranthropus, is probably most closely related to the species Australopithecus africanus within Australopithecus. The closest living relatives of Homo are of the genus Pan, with the ancestors of Pan and Homo estimated to have diverged around 5.7-11 million years ago during the Late Miocene.

In the human skull, a sagittal keel, or sagittal torus, is a thickening of part or all of the midline of the frontal bone, or parietal bones where they meet along the sagittal suture, or on both bones. Sagittal keels differ from sagittal crests, which are found in some earlier hominins and in a range of other mammals. While a proper crest functions in anchoring the muscles of mastication to the cranium, the keel is lower and rounded in cross-section, and the jaw muscles do not attach to it.

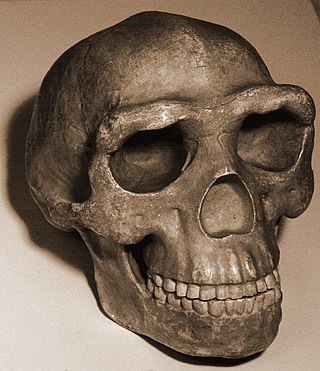

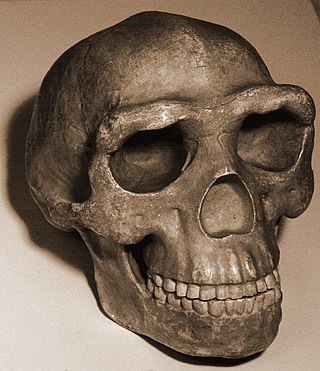

Homo rhodesiensis is the species name proposed by Arthur Smith Woodward (1921) to classify Kabwe 1, a Middle Stone Age fossil recovered from Broken Hill mine in Kabwe, Northern Rhodesia. In 2020, the skull was dated to 324,000 to 274,000 years ago. Other similar older specimens also exist.

Archaic humans is a broad category denoting all species of the genus Homo that are not Homo sapiens. Among the earliest modern human remains are those from Jebel Irhoud in Morocco, Florisbad in South Africa (259 ka), Omo-Kibish I in southern Ethiopia, and Apidima Cave in Southern Greece. Some examples of archaic humans include H. antecessor (1200–770 ka), H. bodoensis (1200–300 ka), H. heidelbergensis (600–200 ka), Neanderthals, H. rhodesiensis (300–125 ka) and Denisovans.

The hypoglossal canal is a foramen in the occipital bone of the skull. It is hidden medially and superiorly to each occipital condyle. It transmits the hypoglossal nerve.

Dali man is the remains of a late Homo erectus or archaic Homo sapiens who lived in the late-mid Pleistocene epoch. The remains comprise a complete fossilized skull, which was discovered by Liu Shuntang in 1978 in Dali County, Shaanxi Province, China.

Teshik-Tash 1 is a Neanderthal skeleton discovered in 1938 in Teshik-Tash Cave, in the Bajsuntau mountain range, Uzbek SSR (Uzbekistan), Central Asia.

The evolution of the brain refers to the progressive development and complexity of neural structures over millions of years, resulting in the diverse range of brain sizes and functions observed across different species today, particularly in vertebrates.

Samu is the nickname given to a fragmentary Middle Pleistocene human occipital, also known as Vertesszolos Man or Vertesszolos occipital, discovered in Vértesszőlős, Central Transdanubia, Hungary.

Neanderthal anatomy differed from modern humans in that they had a more robust build and distinctive morphological features, especially on the cranium, which gradually accumulated more derived aspects, particularly in certain isolated geographic regions. This robust build was an effective adaptation for Neanderthals, as they lived in the cold environments of Europe. In which they also had to operate in Europe's dense forest landscape that was extremely different from the environments of the African grassland plains that Homo sapiens adapted to with a different anatomical build.

The Ndutu skull is the partial cranium of a hominin that has been assigned variously to late Homo erectus, Homo rhodesiensis, and early Homo sapiens, from the Middle Pleistocene, found at Lake Ndutu in northern Tanzania.

Homo naledi is an extinct species of archaic human discovered in 2013 in the Rising Star Cave system, Gauteng province, South Africa, dating to the Middle Pleistocene 335,000–236,000 years ago. The initial discovery comprises 1,550 specimens of bone, representing 737 different skeletal elements, and at least 15 different individuals. Despite this exceptionally high number of specimens, their classification with other Homo species remains unclear.

Xujiayao, located in the Nihewan Basin in China, is an early Late Pleistocene paleoanthropological site famous for its archaic hominin fossils.

Apidima Cave is a complex of five caves located on the western shore of Mani Peninsula in southern Greece. A systematic investigation of the cave has yielded Neanderthal and Homo sapiens fossils from the Palaeolithic era.

Homo longi is an extinct species of archaic human identified from a nearly complete skull, nicknamed 'Dragon Man', from Harbin on the Northeast China Plain, dating to at minimum 146,000 years ago during the Middle Pleistocene. The skull was discovered in 1933 along the Songhua River while the Dongjiang Bridge was under construction for the Manchukuo National Railway. Due to a tumultuous wartime atmosphere, it was hidden and only brought to paleoanthropologists in 2018. H. longi has been hypothesized to be the same species as the Denisovans, but this cannot be confirmed without genetic testing.