Dates

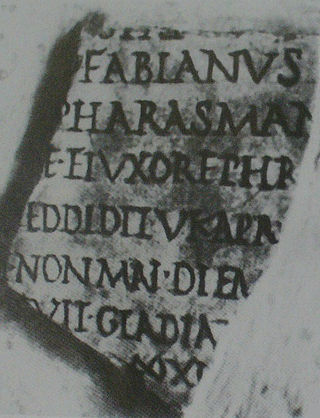

The Romans did not number days of a month sequentially from the 1st through the last day. Instead, they counted back from the three fixed points of the month: the Nones (5th or 7th), the Ides (13th or 15th), and the Kalends (1st) of the following month. The Nones of October was the 7th, and the Ides was the 15th. The last day of October was the pridie Kalendas Novembris, [2] "day before the Kalends of November". Roman counting was inclusive; October 9 was ante diem VII Idūs Octobris, "the 7th day before the Ides of October," usually abbreviated a.d. VII Id. Oct. (or with the a.d. omitted altogether); October 23 was X Kal. Nov., "the 10th day before the Kalends of November."

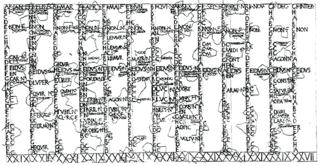

On the calendar of the Roman Republic and early Principate, each day was marked with a letter to denote its religiously lawful status. In March, these were:

- F for dies fasti , days when it was legal to initiate action in the courts of civil law;

- C, for dies comitalis, a day on which the Roman people could hold assemblies (comitia), elections, and certain kinds of judicial proceedings;

- N for dies nefasti , when these political activities and the administration of justice were prohibited;

- NP, the meaning of which remains elusive, but which marked feriae , public holidays;

- EN for endotercissus, an archaic form of intercissus, "cut in half," meaning days that were nefasti in the morning, when sacrifices were being prepared, and in the evening, while sacrifices were being offered, but were fasti in the middle of the day. [3]

By the late 2nd century AD, extant calendars no longer show days marked with these letters, probably in part as a result of calendar reforms undertaken by Marcus Aurelius. [4] Days were also marked with nundinal letters in cycles of A B C D E F G H, to mark the "market week" [5] (these are omitted in the table below).

A dies natalis was an anniversary such as a temple founding or rededication, sometimes thought of as the "birthday" of a deity. During the Imperial period, some of the traditional festivals localized at Rome became less important, and the birthdays and anniversaries of the emperor and his family gained prominence as Roman holidays. On the calendar of military religious observances known as the Feriale Duranum , sacrifices pertaining to Imperial cult outnumber the older festivals, but among the military the importance of Mars was maintained and perhaps magnified. [6] The dies imperii was the anniversary of an emperor's accession. After the mid-1st century AD, a number of dates are added to calendars for spectacles and games (ludi) held in honor of various deities in the venue called a "circus" (ludi circenses). [7] Festivals marked in large letters on extant fasti, represented by festival names in all capital letters on the table, are thought to have been the most ancient holidays, becoming part of the calendar before 509 BC. [8]

Unless otherwise noted, the dating and observances on the following table are from H.H. Scullard, Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic (Cornell University Press, 1981), pp. 189–196.

| Modern date | Roman date | status | Observances |

|---|---|---|---|

| October 1 | Kalendae Octobres | N | • sacrifices for the dies natalis of the Temple of Fides on the Capitoline •Tigillum Sororium • dies natalis of Alexander Severus (reigned 222–235 AD), with circus games [9] |

| 2 | ante diem VI Nonas Octobris | F | |

| 3 | a.d. V Non. Oct. [10] | C | |

| 4 | IV Non. Oct. [11] | C | • Ieiunium Cereris , a fast in honor of Ceres |

| 5 | III Non. Oct. | C dies religiosus | • mundus patet, the second of three days in the year when a mysterious pit or underground chamber was opened |

| 6 | pridie Nonas Octobris (abbrev. prid. Non. Oct.) | C | |

| 7 | Nonae Octobres | F | • dies natalis for Jupiter Fulgur ("Lightning Jupiter") and for Juno Curitis • supplication to Vesta for the birthday of Drusus Caesar (on the Feriale Cumanum , 4–14 AD) [12] |

| 8 | VIII Id. Oct. [13] | F | |

| 9 | VII Id. Oct. | C | • dies natales of temples for the Genius Publicus ("Public Genius"), Fausta Felicitas, and Venus Victrix on the Capitoline |

| 10 | VI Id. Oct. | C | • dies natalis for a restoration of the Temple of Juno Moneta |

| 11 | V Id. Oct. | NP | • MEDITRINALIA • Feriae Iovi |

| 12 | IV Id. Oct. | C | |

| 13 | III Id. Oct. | NP | • FONTINALIA in honor of Fons, outside the Porta Fontinalis |

| 14 | pridie Idūs Octobris (abbrev. prid. Id. Oct.) | EN | • dies natalis for a temple of the Penates on the Velian |

| 15 | Idūs Octobres | NP | • October Horse • regular Feriae Iovi for the Ides • Ludi Capitolini |

| 16 | XVII Kal. Nov. [14] | F | |

| 17 | XVI Kal. Nov. | C | |

| 18 | XV Kal. Nov. | C | • supplication to Spes ("Hope") and Iuventas ("Youth") to commemorate the day Augustus assumed the toga virilis (on the Feriale Cumanum , 4–14 AD) [15] |

| 19 | XIV Kal. Nov. | NP dies religiosus | • ARMILUSTRIUM • Ludi Solis ("Games of the Sun") begin, introduced sometimes after the mid-1st century AD [16] |

| 20 | XIII Kal. Nov. | C | • Ludi Solis continue |

| 21 | XII Kal. Nov. | C | • Ludi Solis continue |

| 22 | XI Kal. Nov. | C | • Ludi Solis conclude |

| 23 | X Kal. Nov. | C | |

| 24 | IX Kal. Nov. | C | |

| 25 | VIII Kal. Nov. | C | |

| 26 | VII Kal. Nov. | C | • Ludi Victoriae Sullanae ("Games for Sulla's Victory") begin, and continue through November 1, from 81 BC until some point during the Imperial period [17] |

| 27 | VI Kal. Nov. | C | • Ludi Victoriae Sullanae continue |

| 28 | V Kal. Nov. | C | • Ludi Victoriae Sullanae continue • Isia, a festival of Isis introduced probably in the 30s or 40s AD, beginning with the Castu Isidis, a day of abstention and loss [18] |

| 29 | IV Kal. Nov. | C | • Ludi Victoriae Sullanae continue • Isia continues |

| 30 | III Kal. Nov. | C | • Ludi Victoriae Sullanae continue • Isia continues |

| 31 | prid. Kal. Nov. | C | • Ludi Victoriae Sullanae continue (through November 1) • Isia continues (through November 3) |