The United Provinces of the Netherlands, or United Provinces, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a federal republic which existed from 1588 to 1795. It was a predecessor state of the Netherlands and the first fully independent Dutch nation state.

In the Low Countries, stadtholder was an office of steward, designated a medieval official and then a national leader. The stadtholder was the replacement of the duke or count of a province during the Burgundian and Habsburg period.

William V was a prince of Orange and the last stadtholder of the Dutch Republic. He went into exile to London in 1795. He was furthermore ruler of the Principality of Orange-Nassau until his death in 1806. In that capacity he was succeeded by his son William.

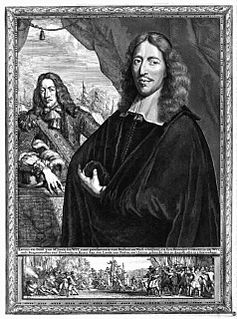

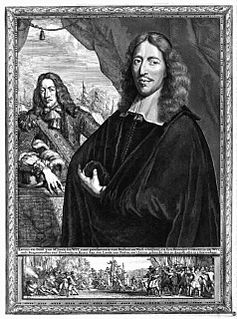

Johan de Witt, lord of Zuid- en Noord-Linschoten, Snelrewaard, Hekendorp en IJsselvere, was a Dutch statesman and a major political figure in the Dutch Republic in the mid-17th century, the First Stadtholderless Period, when its flourishing sea trade in a period of globalization made the republic a leading European trading and seafaring power – now commonly referred to as the Dutch Golden Age. De Witt controlled the Dutch political system from around 1650 until shortly before his murder and cannibalisation by a pro-monarch mob in 1672.

The Patriottentijd was a period of political instability in the Dutch Republic between approximately 1780 and 1787. Its name derives from the Patriots faction who opposed the rule of the stadtholder, William V, Prince of Orange, and his supporters who were known as Orangists

In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, the regenten were the rulers of the Dutch Republic, the leaders of the Dutch cities or the heads of organisations. Though not formally a hereditary "class", they were de facto "patricians", comparable to that ancient Roman class. Since the late Middle Ages Dutch cities had been run by the richer merchant families, who gradually formed a closed group. At first the lower-class citizens in the guilds and schutterijen could unite to form a certain counterbalance to the regenten, but in the course of the 15th century the administration of the cities and towns became oligarchical in character. From the latter part of the 17th century the regent families were able to reserve government offices to themselves via quasi-formal contractual arrangements. In practice they could only be dislodged by political upheavals, like the Orangist revolution of 1747 and the Patriot revolt of 1785.

The Act of Seclusion was an Act of the States of Holland, required by a secret annex in the Treaty of Westminster (1654) between the United Provinces and the Commonwealth of England in which William III, Prince of Orange, was excluded from the office of Stadtholder. Seclusion is defined as the state of being private and away from other people. The First Stadtholderless Period had been heralded in January 1651 by States Party Regenten, among whom the republican-minded brothers Cornelis and Andries de Graeff and their cousins Andries and Cornelis Bicker, during the Grote Vergadering in The Hague, a meeting of representatives of the States of each of the United Provinces. This meeting was convened after the death of stadtholder William II on November 6, 1650, when the States of Holland decided to leave the office of Stadtholder vacant in their province.

The First Stadtholderless Period or Era is the period in the history of the Dutch Republic in which the office of Stadtholder was vacant in five of the seven Dutch provinces. It happened to coincide with the zenith of the Golden Age of the Republic. The term has acquired a negative connotation in 19th-century Orangist Dutch historiography, but whether such a negative view is justified is debatable. Republicans argue that the Dutch state functioned very well under the regime of Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt, despite the fact that it was forced to fight two major wars with England, and several minor wars with other European powers. Thanks to friendly relations with France, a cessation of hostilities with Spain, and the relative weakness of other European great powers, the Republic for a while was able to play a pivotal role in the "European Concert" of nations, even imposing a pax nederlandica in the Scandinavian area. A convenient war with Portugal enabled the Dutch East India Company to take over the remnants of the Portuguese empire in Ceylon and south India. After the end of the war with Spain in 1648, and the attendant end of the Spanish embargo on trade with the Republic that had favored the English, Dutch commerce swept everything before it, in the Iberian Peninsula, the Mediterranean Sea and the Levant, as well as in the Baltic region. Dutch industry, especially textiles, was as yet not hindered by protectionism. As a consequence, the Republic's economy enjoyed its last great economic boom.

The Perpetual Edict was a resolution of the States of Holland passed on 5 August 1667 which abolished the office of Stadtholder in the province of Holland. At approximately the same time, a majority of provinces in the States General of the Netherlands agreed to declare the office of stadtholder incompatible with the office of Captain general of the Dutch Republic.

Henri de Fleury de Coulan, Sieur de Buat, St Sire et La Forest de Gay was a captain of horse in the army of the Dutch Republic, who became embroiled in a celebrated conspiracy during the First Stadtholderless Period to overthrow the regime of Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt in favor of future Stadtholder William III, known as the Buat Conspiracy. He was convicted of treason in 1666 and executed.

The Second Stadtholderless Period or Era is the designation in Dutch historiography of the period between the death of stadtholder William III on March 19, 1702, and the appointment of William IV as stadtholder and captain general in all provinces of the Dutch Republic on May 2, 1747. During this period the office of stadtholder was left vacant in the provinces of Holland, Zeeland, and Utrecht, though in other provinces that office was filled by members of the House of Nassau-Dietz during various periods. During the period the Republic lost its status as a great power and its primacy in world trade. Though its economy declined considerably, causing deindustralization and deurbanization in the maritime provinces, a rentier-class kept accumulating a large capital fund that formed the basis for the leading position the Republic achieved in the international capital market. A military crisis at the end of the period caused the fall of the States-Party regime and the restoration of the Stadtholderate in all provinces. However, though the new stadtholder acquired near-dictatorial powers, this did not improve the situation.

Bicker is a very old Dutch patrician family. The family has played an important role during the Dutch Golden Age. They were at the centre of Amsterdam oligarchy from the beginning of the 17th century until the early 1650s. They leaded the Dutch States Party and were in opposition to the House of Orange. Since 1815 the family belongs to the new Dutch nobility with the honorific of jonkheer or jonkvrouw.

The Dutch Republic was a confederation of seven provinces, which had their own governments and were very independent, and a number of so-called Generality Lands. These latter were governed directly by the States-General, the federal government. The States-General were seated in The Hague and consisted of representatives of each of the seven provinces.

The Dutch States Party was a political faction of the United Provinces of the Netherlands. This republican faction is usually (negatively) defined as the opponents of the Orangist, or Prinsgezinde faction, who supported the monarchical aspirations of the stadtholders, who were usually members of the House of Orange-Nassau. The two factions existed during the entire history of the Republic since the Twelve Years' Truce, be it that the role of "usual opposition party" of the States party was taken over by the Patriots after the Orangist revolution of 1747. The States party was in the ascendancy during the First Stadtholderless Period and the Second Stadtholderless Period.

The Loevestein faction or the Loevesteiners were a Dutch States Party in the second half of the 17th century in the County of Holland, the dominant province of the Dutch Republic. It claimed to be the party of "true freedom" against the stadtholderate of the House of Orange-Nassau, and sought to establish a purely republican form of government in the Northern Netherlands.

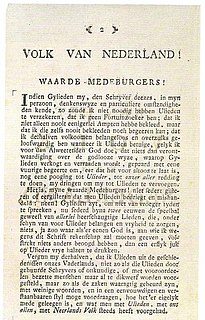

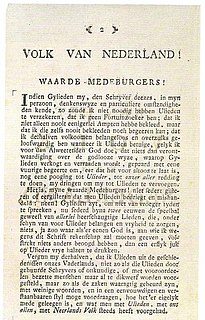

Aan het Volk van Nederland was a pamphlet distributed by window-covered carriages across all major cities of the Dutch Republic in the night of 25 to 26 September 1781. It claimed the entire political system, dominated by the Orange hereditary stadtholderate, was corrupt and had to be overthrown in favour of a democratic republic. The pamphlet became the creed of the Patriots.

The Act of Guarantee of the hereditary stadtholderate was a document from 1788, in which the seven provinces of the States General and the representative of Drenthe declared, amongst other things, that the admiralty and captain-generalship were hereditary, and together with the hereditary stadtholderate would henceforth be an integrated part of the constitution of the Dutch Republic. Moreover, members of the House of Orange-Nassau would have the exclusive privilege to hold the office. The Act was in force until the Batavian Republic was established in 1795.

The Battle of Jutphaas, also known as the Battle of the Vaart or the Battle of Vreeswijk, occurred on 9 May 1787 on the banks of the Vaartsche Rijn canal near Jutphaas and Vreeswijk between Orangists and Patriots.

The Attack on Amsterdam in July 1650 was part of a planned coup d'état by stadtholder William II, Prince of Orange to break the power of the regenten in the Dutch Republic, especially the County of Holland. The coup failed, because the army of the Frisian stadtholder William Frederick, Prince of Nassau-Dietz got lost on the way to Amsterdam in the rainy night of 29 to 30 July. It was discovered, and once the city had been warned, it had enough time to prepare for an attack. The attempted coup made the House of Orange extremely unpopular for a lengthy period of time, and was one of the main reasons for the origins of the First Stadtholderless Period (1650–1672).

Elie Luzac was a Dutch jurist, journalist, writer of philosophical, historical and political literature, and book-seller, who was considered an important ideologue of the "democratic wing" of the Orangist movement, both after the Orangist restoration in the Dutch Republic in 1748, and during the Patriottentijd.