Fair trade is a term for an arrangement designed to help producers in developing countries achieve sustainable and equitable trade relationships. The fair trade movement combines the payment of higher prices to exporters with improved social and environmental standards. The movement focuses in particular on commodities, or products that are typically exported from developing countries to developed countries but is also used in domestic markets, most notably for handicrafts, coffee, cocoa, wine, sugar, fruit, flowers and gold.

In marketing, a product is an object, or system, or service made available for consumer use as of the consumer demand; it is anything that can be offered to a market to satisfy the desire or need of a customer. In retailing, products are often referred to as merchandise, and in manufacturing, products are bought as raw materials and then sold as finished goods. A service is also regarded as a type of product.

A farmers' market is a physical retail marketplace intended to sell foods directly by farmers to consumers. Farmers' markets may be indoors or outdoors and typically consist of booths, tables or stands where farmers sell their produce, live animals and plants, and sometimes prepared foods and beverages. Farmers' markets exist in many countries worldwide and reflect the local culture and economy. The size of the market may be just a few stalls or it may be as large as several city blocks. Due to their nature, they tend to be less rigidly regulated than retail produce shops.

Three European Union schemes of geographical indications and traditional specialties, known as protected designation of origin (PDO), protected geographical indication (PGI), and traditional speciality guaranteed (TSG), promote and protect names of agricultural products and foodstuffs. Products registered under one of the three schemes may be marked with the logo for that scheme to help identify those products. The schemes are based on the legal framework provided by the EU Regulation No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 November 2012 on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs. This regulation applies within the EU as well as in Northern Ireland. Protection of the registered products is gradually expanded internationally via bilateral agreements between the EU and non-EU countries. It ensures that only products genuinely originating in that region are allowed to be identified as such in commerce. The legislation first came into force in 1992. The purpose of the law is to protect the reputation of the regional foods, promote rural and agricultural activity, help producers obtain a premium price for their authentic products, and eliminate the unfair competition and misleading of consumers by non-genuine products, which may be of inferior quality or of different flavour. Critics argue that many of the names, sought for protection by the EU, have become commonplace in trade and should not be protected.

The organic movement broadly refers to the organizations and individuals involved worldwide in the promotion of organic food and other organic products. It started during the first half of the 20th century, when modern large-scale agricultural practices began to appear.

Organic certification is a certification process for producers of organic food and other organic agricultural products, in the European Union more commonly known as ecological or biological products. In general, any business directly involved in food production can be certified, including seed suppliers, farmers, food processors, retailers and restaurants. A lesser known counterpart is certification for organic textiles that includes certification of textile products made from organically grown fibres.

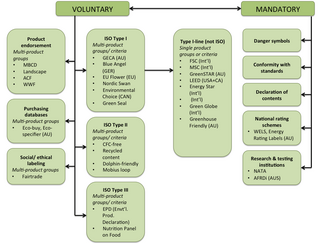

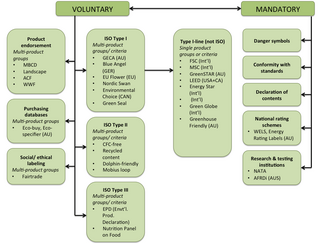

Ecolabels and Green Stickers are labeling systems for food and consumer products. The use of ecolabels is voluntary, whereas green stickers are mandated by law; for example, in North America major appliances and automobiles use Energy Star. They are a form of sustainability measurement directed at consumers, intended to make it easy to take environmental concerns into account when shopping. Some labels quantify pollution or energy consumption by way of index scores or units of measurement, while others assert compliance with a set of practices or minimum requirements for sustainability or reduction of harm to the environment. Many ecolabels are focused on minimising the negative ecological impacts of primary production or resource extraction in a given sector or commodity through a set of good practices that are captured in a sustainability standard. Through a verification process, usually referred to as "certification", a farm, forest, fishery, or mine can show that it complies with a standard and earn the right to sell its products as certified through the supply chain, often resulting in a consumer-facing ecolabel.

The food industry is a complex, global network of diverse businesses that supplies most of the food consumed by the world's population. The food industry today has become highly diversified, with manufacturing ranging from small, traditional, family-run activities that are highly labour-intensive, to large, capital-intensive and highly mechanized industrial processes. Many food industries depend almost entirely on local agriculture, animal farms, produce, and/or fishing.

Food safety is used as a scientific method/discipline describing handling, preparation, and storage of food in ways that prevent foodborne illness. The occurrence of two or more cases of a similar illness resulting from the ingestion of a common food is known as a food-borne disease outbreak. This includes a number of routines that should be followed to avoid potential health hazards. In this way, food safety often overlaps with food defense to prevent harm to consumers. The tracks within this line of thought are safety between industry and the market and then between the market and the consumer. In considering industry-to-market practices, food safety considerations include the origins of food including the practices relating to food labeling, food hygiene, food additives and pesticide residues, as well as policies on biotechnology and food and guidelines for the management of governmental import and export inspection and certification systems for foods. In considering market-to-consumer practices, the usual thought is that food ought to be safe in the market and the concern is safe delivery and preparation of the food for the consumer. Food safety, nutrition and food security are closely related. Unhealthy food creates a cycle of disease and malnutrition that affects infants and adults as well.

Food marketing brings together the food producer and the consumer through a chain of marketing activities.

Organic farming is practiced around the globe, but the markets for sale are strongest in North America and Europe, while the greatest dedicated area is accounted for by Australia, the greatest number of producers are in India, and the Falkland Islands record the highest share of agricultural land dedicated to organic production.

Organic food, ecological food, or biological food are foods and drinks produced by methods complying with the standards of organic farming. Standards vary worldwide, but organic farming features practices that cycle resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity. Organizations regulating organic products may restrict the use of certain pesticides and fertilizers in the farming methods used to produce such products. Organic foods are typically not processed using irradiation, industrial solvents, or synthetic food additives.

The term food system describes the interconnected systems and processes that influence nutrition, food, health, community development, and agriculture. A food system includes all processes and infrastructure involved in feeding a population: growing, harvesting, processing, packaging, transporting, marketing, consumption, distribution, and disposal of food and food-related items. It also includes the inputs needed and outputs generated at each of these steps. Food systems fall within agri-food systems, which encompass the entire range of actors and their interlinked value-adding activities in the primary production of food and non-food agricultural products, as well as in food storage, aggregation, post-harvest handling, transportation, processing, distribution, marketing, disposal, and consumption. A food system operates within and is influenced by social, political, economic, technological and environmental contexts. It also requires human resources that provide labor, research and education. Food systems are either conventional or alternative according to their model of food lifespan from origin to plate. Food systems are dependent on a multitude of ecosystem services. For example, natural pest regulations, microorganisms providing nitrogen-fixation, and pollinators.

Sustainability standards and certifications are voluntary guidelines used by producers, manufacturers, traders, retailers, and service providers to demonstrate their commitment to good environmental, social, ethical, and food safety practices. There are over 400 such standards across the world.

Sustainable products are those products that provide environmental, social and economic benefits while protecting public health and environment over their whole life cycle, from the extraction of raw materials until the final disposal.

An alternative purchase network (APN) is a contemporary commerce channel established as an alternative to perceived consumerism, and the cultural and economic hegemony of the global market. Alternative purchase networks aim to promote ethical shopping behaviour, which has an environmentally-friendly approach and considers local realities.

Green consumption is related to sustainable development or sustainable consumer behaviour. It is a form of consumption that safeguards the environment for the present and for future generations. It ascribes to consumers responsibility or co-responsibility for addressing environmental problems through the adoption of environmentally friendly behaviors, such as the use of organic products, clean and renewable energy, and the choice of goods produced by companies with zero, or almost zero, impact.

Critical consumption is the conscious choice to buy or not buy a product because of ethical and political beliefs. The critical consumer considers characteristics of the product and its realization, such as environmental sustainability and respect of workers’ rights. Critical consumers take responsibility for the environmental, social, and political effects of their choices. The critical consumer sympathizes with certain social movement goals and contributes towards them by modifying their consumption behavior.

COSMOS stands for "COSMetic Organic and Natural Standard", which sets certification requirements for organic and natural cosmetics products in the Europe. The standard is recognized globally by the cosmetic industry. By adhering to specific guidelines, cosmetics marketers can use COSMOS signatures, which are registered trademarks, on packaging to confirm the products meet minimum industry requirements to be considered organic or natural.

Halal meat is meat of animal slaughtered according to Quran and Sunnah and thus permitted for consumption by Muslims.