Ostentatio genitalium (Latin for "display of the genitals") is a term coined by Leo Steinberg in 1983 [1] that refers to artistic emphasis of the genitals of Christ in Renaissance paintings. It can take the form of exposed display, demonstrative hand positions, (self) touch, exaggerated textile draping, etc. The term adapted the existing feature in iconography of the ostentatio vulnerum or "display of wounds", where Christ indicates the wound in his side, as in the Doubting Thomas episode, or depictions of the Man of Sorrows .

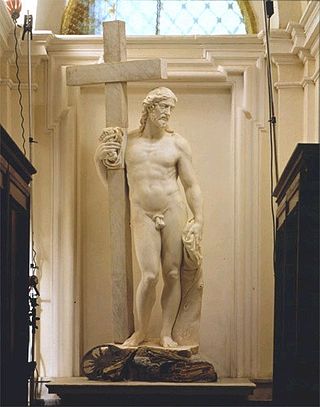

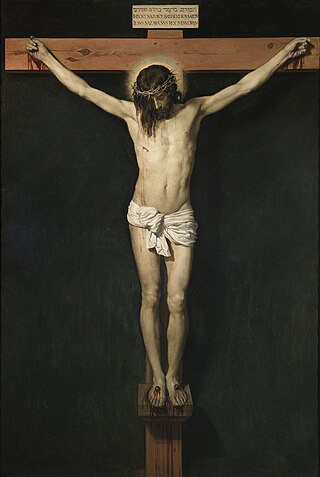

Ostentatio genitalium was a tendency opposite to the Byzantine practice of depicting a sexless Jesus (with flattened abdomen covered by veils), with first examples starting around 1260, gaining popularity in the Renaissance, and tapering off in the seventeenth-century. [1] In the art of the 15th and 16th centuries in particular, there are numerous examples of the genitals being the focus of depictions not only because of their position, but also because of perspective and multiple pointers, as well as the artful arrangement of a loincloth, not usually found in older art. In principle, the genitals of Christ are shown unveiled in paintings of baby Jesus, while in scenes from the Passion, elaborately draped loincloths emphasize the genital region. Historically, the ostentatio genitalium is interpreted as an expression of the greatest possible self-humiliation of God assuming a mortal form, that, in words of Steinberg was “delivered from sin and shame” [2]

The wider circle of corresponding representations includes portraits with the circumcision of Jesus, although in these Renaissance paintings Christ's genitals are often covered (e.g. by a hand of Mary). Art scholars such as Steinberg also see a connection between the circumcision motif and some depictions of the Crucifixion, in which the blood escaping from the side wound runs over the loincloth, creating an artistic connection between the first and last wound. A similar level of meaning is exhibited by images of the Entombment, in which a hand of the dead Christ rests on his genitals.

There are many theories about the origin of ostentatio genitalium. One of them connects it with the rise of Franciscan spirituality in the 13th century, and its slogan nudus nudum Christum sequi (“naked to follow the naked Christ”). Another sees it as part of the Renaissance movement towards anatomical correctness and naturalism in art. [1]

Art historians such as Jean-Claude Schmitt or Jérôme Baschet , also regard the covering of the genitals with a deliberately puffed-out loincloth as a symbolic castration, while at the same time they recognize a feminization of the body of Christ in the side wound, which is occasionally depicted as female genitals. The emphasis and simultaneous concealment of sexual characteristics is intended to indicate the fertility of Jesus, which, however, is not reflected in bodily but in spiritual descendants.

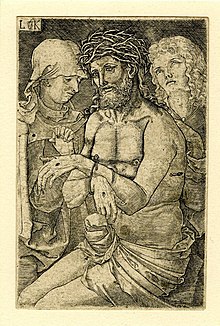

In Renaissance art, ostentatio genitalium avoids the question of Christ's sexuality in that the erect member only occurs in children's portraits or in the suffering or already dead Christ, in the latter in a meaning level that indicates the overcoming of death. A prominent example of this is the Man of Sorrows by Maarten van Heemskerck, c. 1550, with stigmata and a crown of thorns. Other examples are Man of Sorrows by Ludwig Krug from around 1520 and Hans Schäufelin's Crucifixion of Christ from 1515. By embedding the phallic depictions of Christ in the sorrowful Passion story, the depictions also negate lust and sexualization at the same time. In doing so, they follow the theological moral concepts of their time and suggest chastity as a means of regaining salvation. In discussion with Augustine of Hippo, Steinberg states the paradoxical atonement for the Fall of Man in ostentatio genitalium: it creates an “erection-resurrection equation”, which makes the viewers understand the holy mystery of "mortified-vivified flesh". [3]