Santa Ana de los Cuatro Ríos de Cuenca, commonly referred to as Cuenca, is the capital and largest city of the Azuay Province of Ecuador. Cuenca is located in the highlands of Ecuador at about 2,560 metres above sea level, with an urban population of 361,524 and a population of 596,101 in the Cuenca Canton.

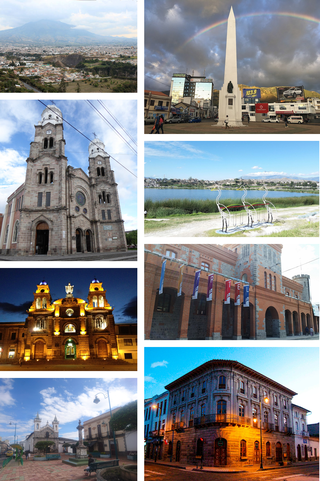

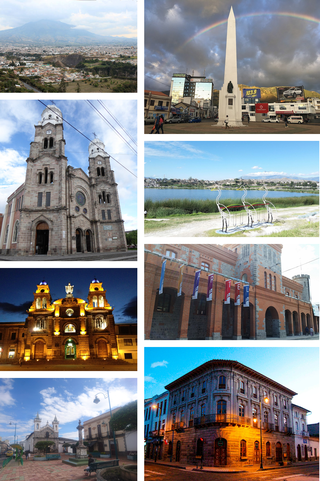

Ibarra is a city in northern Ecuador and the capital of the Imbabura Province. It lies at the foot of the Imbabura Volcano and on the left bank of the Tahuando river. It is located about 70 kilometres (43 mi) northeast of Ecuador's capital Quito.

Quechua people or Quichua people may refer to any of the indigenous peoples of South America who speak the Quechua languages, which originated among the Indigenous people of Peru. Although most Quechua speakers are native to Peru, there are some significant populations in Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, and Argentina.

Huamachuco District is one of the districts of the Sánchez Carrión province located in La Libertad Region in Peru. It contains the capital of the province and the important archeological site of Marcahuamachuco, which was active, likely as an oracle center and place for religious and political elites, about 350 CE to 1100 CE.

The Guandera Biological Station is a biological station established in 1994 and situated in the northern inter-Andean valley of Ecuador. The station is managed by the Jatun Sacha Foundation and is located in Ecuador's Carchi Province..

The Cara or Caranqui culture flourished in coastal Ecuador, in what is now Manabí Province, in the first millennium CE.

Incan agriculture was the culmination of thousands of years of farming and herding in the high-elevation Andes mountains of South America, the coastal deserts, and the rainforests of the Amazon basin. These three radically different environments were all part of the Inca Empire and required different technologies for agriculture. Inca agriculture was also characterized by the variety of crops grown, the lack of a market system and money, and the unique mechanisms by which the Incas organized their society. Andean civilization was "pristine"—one of six civilizations worldwide which were indigenous and not derivative from other civilizations. Most Andean crops and domestic animals were likewise pristine—not known to other civilizations. Potatoes, tomatoes, chile peppers, and quinoa were among the many unique crops; Camelids and guinea pigs were the unique domesticated animals.

The Andean textile tradition once spanned from the Pre-Columbian to the Colonial era throughout the western coast of South America, but was mainly concentrated in Peru. The arid desert conditions along the coast of Peru have allowed for the preservation of these dyed textiles, which can date to 6000 years old. Many of the surviving textile samples were from funerary bundles, however, these textiles also encompassed a variety of functions. These functions included the use of woven textiles for ceremonial clothing or cloth armor as well as knotted fibers for record-keeping. The textile arts were instrumental in political negotiations, and were used as diplomatic tools that were exchanged between groups. Textiles were also used to communicate wealth, social status, and regional affiliation with others. The cultural emphasis on the textile arts was often based on the believed spiritual and metaphysical qualities of the origins of materials used, as well as cosmological and symbolic messages within the visual appearance of the textiles. Traditionally, the thread used for textiles was spun from indigenous cotton plants, as well as alpaca and llama wool.

Pukara is a defensive hilltop site or fortification built by the prehispanic and historic inhabitants of the central Andean area. In some cases, these sites acted as temporary fortified refuges during periods of increased conflict, while other sites show evidence for permanent occupation. Emerging as a major site type during the Late Intermediate Period, the pukara form was adopted in some areas by the Inca military in contested borderlands of the Inca Empire. The Spanish also referred to the Mapuche earthen forts built during the Arauco War in the 16th and 17th centuries by this term.

Indigenous peoples in Ecuador, or Native Ecuadorians, are the groups of people who were present in what became Ecuador before the Spanish colonization of the Americas. The term also includes their descendants from the time of the Spanish conquest to the present. Their history, which encompasses the last 11,000 years, reaches into the present; 25 percent of Ecuador's population is of indigenous heritage, while another 55-65 percent are Mestizos of mixed indigenous and European heritage. Genetic analysis indicates that Ecuadorian Mestizos are of predominantly indigenous ancestry.

El Quinche is a city of Ecuador, in the Pichincha Province, about 22 km (14 mi) in a straight line distance northeast of the city of Quito. The city, administratively a rural parish of the canton of Quito, is located in the valley of the headwaters of the Guayllabamba River, to the west of Pambamarca. It borders Cayambe Canton to the northeast.

The Lupaca, Lupaka, or Lupaqa people were one of the divisions of the ancestral Aymaras. The Lupaca lived for many centuries near Lake Titicaca in Peru and their lands possibly extended into Bolivia. The Lupacas and other Aymara peoples formed powerful kingdoms after the collapse of the Tiwanaku Empire in the 11th century. In the mid 15th century they were conquered by the Inca Empire and in the 1530s came under the control of the Spanish Empire.

The Andean civilizations were South American complex societies of many indigenous people. They stretched down the spine of the Andes for 4,000 km (2,500 mi) from southern Colombia, to Ecuador and Peru, including the deserts of coastal Peru, to north Chile and northwest Argentina. Archaeologists believe that Andean civilizations first developed on the narrow coastal plain of the Pacific Ocean. The Caral or Norte Chico civilization of coastal Peru is the oldest known civilization in the Americas, dating back to 3500 BCE. Andean civilization is one of the six "pristine" civilizations of the world, created independently and without influence by other civilizations.

The vertical archipelago is a term coined by sociologist and anthropologist John Victor Murra under the influence of economist Karl Polanyi to describe the native Andean agricultural economic model of accessing and distributing resources. While some cultures developed market economies, the predominant models were systems of barter and shared labor. These reached their greatest development under the Inca Empire. Scholars have identified four distinct ecozones, at different elevations.

Yawarkucha or Yawar Kucha, hispanicized spellings Yaguarcocha, Yahuarcocha) is a lake in Ecuador located in the eastern outskirts of the city of Ibarra in Imbabura Province, Ibarra Canton. The lake is about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) long and wide and has an elevation of 2,190 metres (7,190 ft) above sea level. The lake was formed from glacial meltwater about 10,000 BCE.

Cochasquí is the "most extensive and most important complex" of pre-Columbian and pre-Inca Empire ruins in northern Ecuador. The site lies some 30 kilometres (19 mi) northeast of Quito in Pedro Moncayo Canton in Pichincha Province at 3,040 metres (9,970 ft) above sea level.

A chuspas is a pouch that is used to carry coca leaves, used primarily in the Andean region of South America. Both textiles and coca are very important to the people in Andean South America. These chuspas are a vital piece of culture and are especially important to combat the bitter cold in the mountainous zones of the Andes. These bags are also a way to showcase the cloth which in itself is a primary artistic medium. Highland textiles are traditionally woven from the hair of native camelids, usually the domesticated alpacas and llamas, and more rarely, wild vicuña and guanaco. These pouches are important symbols of social identity. As part of this tradition, chuspas show to the rest of their people how skilled they are in weaving. They can express their artistic skills and display their cultural affiliation by creating these chuspas.

The Inca-Caranqui archaeological site is located in the village of Caranqui on the southern outskirts of the city of Ibarra, Ecuador. The ruin is located in a fertile valley at an elevation of 2,299 metres (7,543 ft). The region around Caranqui, extending into the present day country of Colombia, was the northernmost outpost of the Inca Empire and the last to be added to the empire before the Spanish conquest of 1533. The archaeological region is also called the Pais Caranqui.

The Pambamarca Fortress Complex consists of the ruins of a large number of pukaras and other constructions of the Inca Empire. The fortresses were constructed in the late 15th century by the Incas to overcome the opposition of the people of the Cayambe chiefdom to the expansion of the Incas in the Andes highlands of present-day northern Ecuador. The Pambamarca fortresses are located in Cayambe Canton in Pichincha Province about 32 kilometres (20 mi) in a straight-line distance northeast of the city of Quito.

Rumicucho or Pucara de Rumicucho is an archaeological site of the Inca Empire in the parroquia of San Antonio de Pichincha, in Quito Canton, Pichincha Province. Ecuador. Rumicucho is a pucara located 23 kilometres (14 mi) in a straight-line distance north of the city of Quito at an elevation of 2,401 metres (7,877 ft). Rumicucho in the Quechua language means "stone corner", perhaps referring to its strategic location between the territory of the Yumbo people to the east and the chiefdoms of the Pais Caranqui to the north.