a. ^ Lovejoy is best known by the name C. Owen Lovejoy, which he uses for publications. His entry in The Cambridge Dictionary of Human Biology and Evolution lists him by this name. [1]

Related Research Articles

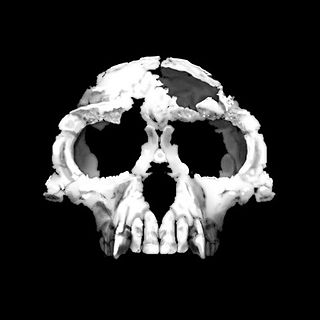

Ardipithecus is a genus of an extinct hominine that lived during the Late Miocene and Early Pliocene epochs in the Afar Depression, Ethiopia. Originally described as one of the earliest ancestors of humans after they diverged from the chimpanzees, the relation of this genus to human ancestors and whether it is a hominin is now a matter of debate. Two fossil species are described in the literature: A. ramidus, which lived about 4.4 million years ago during the early Pliocene, and A. kadabba, dated to approximately 5.6 million years ago. Initial behavioral analysis indicated that Ardipithecus could be very similar to chimpanzees, however more recent analysis based on canine size and lack of canine sexual dimorphism indicates that Ardipithecus was characterised by reduced aggression, and that they more closely resemble bonobos.

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where a tetrapod moves by means of its two rear limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped, meaning 'two feet'. Types of bipedal movement include walking or running and hopping.

Homininae, also called "African hominids" or "African apes", is a subfamily of Hominidae. It includes two tribes, with their extant as well as extinct species: 1) the tribe Hominini ―and 2) the tribe Gorillini (gorillas). Alternatively, the genus Pan is sometimes considered to belong to its own third tribe, Panini. Homininae comprises all hominids that arose after orangutans split from the line of great apes. The Homininae cladogram has three main branches, which lead to gorillas, and to humans and chimpanzees via the tribe Hominini and subtribes Hominina and Panina. There are two living species of Panina and two living species of gorillas, but only one extant human species. Traces of extinct Homo species, including Homo floresiensis have been found with dates as recent as 40,000 years ago. Organisms in this subfamily are described as hominine or hominines.

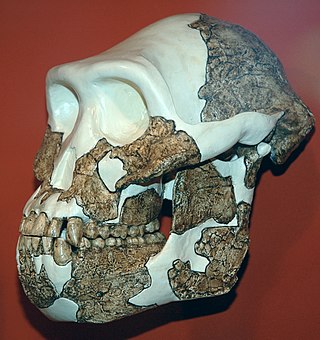

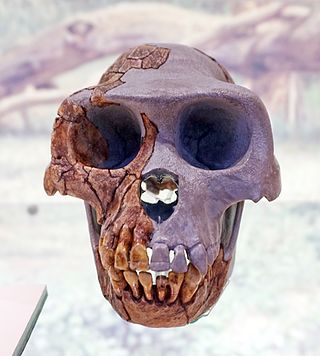

Australopithecus is a genus of early hominins that existed in Africa during the Pliocene and Early Pleistocene. The genera Homo, Paranthropus, and Kenyanthropus evolved from some Australopithecus species. Australopithecus is a member of the subtribe Australopithecina, which sometimes also includes Ardipithecus, though the term "australopithecine" is sometimes used to refer only to members of Australopithecus. Species include A. garhi, A. africanus, A. sediba, A. afarensis, A. anamensis, A. bahrelghazali and A. deyiremeda. Debate exists as to whether some Australopithecus species should be reclassified into new genera, or if Paranthropus and Kenyanthropus are synonymous with Australopithecus, in part because of the taxonomic inconsistency.

Australopithecus afarensis is an extinct species of australopithecine which lived from about 3.9–2.9 million years ago (mya) in the Pliocene of East Africa. The first fossils were discovered in the 1930s, but major fossil finds would not take place until the 1970s. From 1972 to 1977, the International Afar Research Expedition—led by anthropologists Maurice Taieb, Donald Johanson and Yves Coppens—unearthed several hundreds of hominin specimens in Hadar, Ethiopia, the most significant being the exceedingly well-preserved skeleton AL 288-1 ("Lucy") and the site AL 333. Beginning in 1974, Mary Leakey led an expedition into Laetoli, Tanzania, and notably recovered fossil trackways. In 1978, the species was first described, but this was followed by arguments for splitting the wealth of specimens into different species given the wide range of variation which had been attributed to sexual dimorphism. A. afarensis probably descended from A. anamensis and is hypothesised to have given rise to Homo, though the latter is debated.

Paleoanthropology or paleo-anthropology is a branch of paleontology and anthropology which seeks to understand the early development of anatomically modern humans, a process known as hominization, through the reconstruction of evolutionary kinship lines within the family Hominidae, working from biological evidence and cultural evidence.

Australopithecus anamensis is a hominin species that lived approximately between 4.2 and 3.8 million years ago and is the oldest known Australopithecus species, living during the Plio-Pleistocene era.

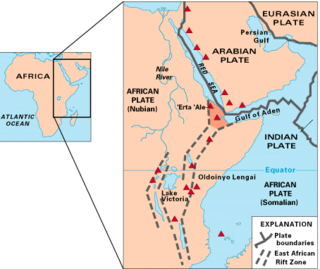

The Afar Triangle is a geological depression caused by the Afar Triple Junction, which is part of the Great Rift Valley in East Africa. The region has disclosed fossil specimens of the very earliest hominins; that is, the earliest of the human clade, and it is thought by some paleontologists to be the cradle of the evolution of humans. The Depression overlaps the borders of Eritrea, Djibouti and the entire Afar Region of Ethiopia; and it contains the lowest point in Africa, Lake Assal, Djibouti, at 155 m (509 ft) below sea level.

Australopithecina or Hominina is a subtribe in the tribe Hominini. The members of the subtribe are generally Australopithecus, and it typically includes the earlier Ardipithecus, Orrorin, Sahelanthropus, and Graecopithecus. All these closely related species are now sometimes collectively termed australopiths or homininians. They are the extinct, close relatives of humans and, with the extant genus Homo, comprise the human clade. Members of the human clade, i.e. the Hominini after the split from the chimpanzees, are now called Hominina.

Tim D. White is an American paleoanthropologist and Professor of Integrative Biology at the University of California, Berkeley. He is best known for leading the team which discovered Ardi, the type specimen of Ardipithecus ramidus, a 4.4 million-year-old likely human ancestor. Prior to that discovery, his early career was notable for his work on Lucy as Australopithecus afarensis with discoverer Donald Johanson.

The Middle Awash is a paleoanthropological research area in the northwest corner of Gabi Rasu in the Afar Region along the Awash River in Ethiopia's Afar Depression. It is a unique natural laboratory for the study of human origins and evolution and a number of fossils of the earliest hominins, particularly of the Australopithecines, as well as some of the oldest known Olduwan stone artifacts, have been found at the site—all of late Miocene, the Pliocene, and the very early Pleistocene times, that is, about 5.6 million years ago (mya) to 2.5 mya. It is broadly thought that the divergence of the lines of the earliest humans (hominins) and of chimpanzees (hominids) was completed near the beginning of that time range, or sometime between seven and five mya. However, the larger community of scientists provide several estimates for periods of divergence that imply a greater range for this event, see CHLCA: human-chimpanzee split.

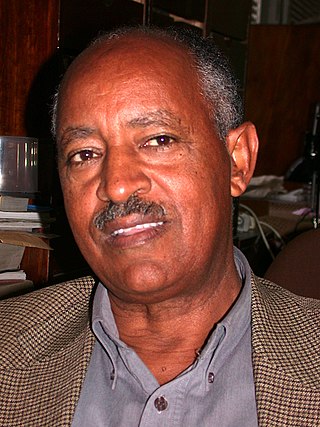

Yohannes Haile-SelassieAmbaye is an Ethiopian paleoanthropologist. An authority on pre-Homo sapiens hominids, he particularly focuses his attention on the East African Rift and Middle Awash valleys. He was curator of Physical Anthropology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History from 2002 until 2021, and now is serving as the director of the Arizona State University Institute of Human Origins. Since founding the institute in 1981, he has been the third director after Donald Johanson and William Kimbel.

In human anatomy, the third trochanter is a bony projection occasionally present on the proximal femur near the superior border of the gluteal tuberosity. When present, it is oblong, rounded, or conical in shape and sometimes continuous with the gluteal ridge. It generally occurs bilaterally without significant side to side dimorphism. A structure of minor importance in humans, the incidence of the third trochanter varies from 17 to 72% between ethnic groups and it is frequently reported as more common in females than in males. Structures analogous to the third trochanter are present in other mammals, including some primates. It is called the third trochanter in reference to the greater and lesser trochanters that are always present on the femur.

Ardipithecus kadabba is the scientific classification given to fossil remains "known only from teeth and bits and pieces of skeletal bones", originally estimated to be 5.8 to 5.2 million years old, and later revised to 5.77 to 5.54 million years old. According to the first description, these fossils are close to the common ancestor of chimps and humans. Their development lines are estimated to have parted 6.5–5.5 million years ago. It has been described as a "probable chronospecies" of A. ramidus. Although originally considered a subspecies of A. ramidus, in 2004 anthropologists Yohannes Haile-Selassie, Gen Suwa, and Tim D. White published an article elevating A. kadabba to species level on the basis of newly discovered teeth from Ethiopia. These teeth show "primitive morphology and wear pattern" which demonstrate that A. kadabba is a distinct species from A. ramidus.

Ardipithecus ramidus is a species of australopithecine from the Afar region of Early Pliocene Ethiopia 4.4 million years ago (mya). A. ramidus, unlike modern hominids, has adaptations for both walking on two legs (bipedality) and life in the trees (arboreality). However, it would not have been as efficient at bipedality as humans, nor at arboreality as non-human great apes. Its discovery, along with Miocene apes, has reworked academic understanding of the chimpanzee–human last common ancestor from appearing much like modern day chimpanzees, orangutans and gorillas to being a creature without a modern anatomical cognate.

Berhane Asfaw is an Ethiopian paleontologist of Rift Valley Research Service, who co-discovered human skeletal remains at Herto Bouri, Ethiopia later classified as Homo sapiens idaltu, proposed as an early subspecies of anatomically modern humans.

Ardi (ARA-VP-6/500) is the designation of the fossilized skeletal remains of an Ardipithecus ramidus, thought to be an early human-like female anthropoid 4.4 million years old. It is the most complete early hominid specimen, with most of the skull, teeth, pelvis, hands and feet, more complete than the previously known Australopithecus afarensis specimen called "Lucy." In all, 125 different pieces of fossilized bone were found.

Changes to the dental morphology and jaw are major elements of hominid evolution. These changes were driven by the types and processing of food eaten. The evolution of the jaw is thought to have facilitated encephalization, speech, and the formation of the uniquely human chin.

Gen Suwa is a Japanese paleoanthropologist. He is known for his contributions to the understanding of the evolution of early hominids, including the discovery of a tooth from a hominid that was more than one million years older than the oldest previously known hominid. The discovery changed scientific opinion regarding the ancestral splits between humans, chimps and gorillas.

The savannah hypothesis is a hypothesis that human bipedalism evolved as a direct result of human ancestors' transition from an arboreal lifestyle to one on the savannas. According to the hypothesis, millions of years ago hominins left the woodlands that had previously been their natural habitat, and adapted to their new habitat by walking upright.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Larry L Mai; Marcus Young Owl; M Patricia Kersting (2005), The Cambridge Dictionary of Human Biology and Evolution, Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 310, ISBN 978-0-521-66486-8

- ↑ Lovejoy, C. Owen (23 January 1981), "The Origin of Man", Science, 211 (4480): 341–350, Bibcode:1981Sci...211..341L, doi:10.1126/science.211.4480.341, PMID 17748254

- 1 2 Carol Biliczky (9 October 2009), "Discovery Channel special features KSU professor", Akron Beacon Journal

- ↑ list of publications, Kent State University: Department of Anthropology, archived from the original on 2009-11-23, retrieved 2009-10-14

- 1 2 3 4 David Gardner (2007), "Owen C. Lovejoy", Anthropology Biography Web, Minnesota State University, Mankato, archived from the original on 2009-12-01, retrieved 2009-10-14

- ↑ "Special issue: Ardipithecus ramidus", Science, 326 (5949): 60–108, 2 October 2009, doi:10.1126/science.326.5949.60-b

- ↑ Mai, L.L., Owl, M.Y., & Kersting, M.P. (2005), p. 441

- 1 2 3 4 Melissa Edler (4 June 2007), "Dr. C. Owen Lovejoy Newly Elected to Membership in the National Academy of Sciences", eInside, Kent State University