The Dictum of Kenilworth, issued on 31 October 1266, was a pronouncement designed to reconcile the rebels of the Second Barons' War with the royal government of England. After the baronial victory at the Battle of Lewes in 1264, Simon de Montfort took control of royal government, but at the Battle of Evesham the next year Montfort was killed, and King Henry III restored to power. A group of rebels held out in the stronghold of Kenilworth Castle, however, and their resistance proved difficult to crush.

Edward I, also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he was Lord of Ireland, and from 1254 to 1306 he ruled Gascony as Duke of Aquitaine in his capacity as a vassal of the French king. Before his accession to the throne, he was commonly referred to as the Lord Edward. The eldest son of Henry III, Edward was involved from an early age in the political intrigues of his father's reign. In 1259, he briefly sided with a baronial reform movement, supporting the Provisions of Oxford. After reconciliation with his father, he remained loyal throughout the subsequent armed conflict, known as the Second Barons' War. After the Battle of Lewes, Edward was held hostage by the rebellious barons, but escaped after a few months and defeated the baronial leader Simon de Montfort at the Battle of Evesham in 1265. Within two years, the rebellion was extinguished and, with England pacified, Edward left to join the Ninth Crusade to the Holy Land in 1270. He was on his way home in 1272 when he was informed of his father's death. Making a slow return, he reached England in 1274 and was crowned at Westminster Abbey.

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, later sometimes referred to as Simon V de Montfort to distinguish him from his namesake relatives, was an English nobleman of French origin and a member of the English peerage, who led the baronial opposition to the rule of King Henry III of England, culminating in the Second Barons' War. Following his initial victories over royal forces, he became de facto ruler of the country, and played a major role in the constitutional development of England.

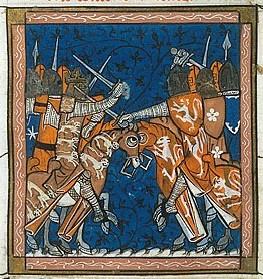

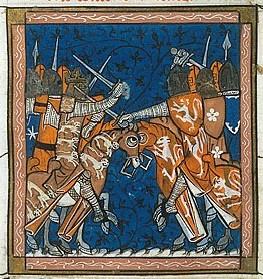

The Battle of Lewes was one of two main battles of the conflict known as the Second Barons' War. It took place at Lewes in Sussex, on 14 May 1264. It marked the high point of the career of Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, and made him the "uncrowned King of England". Henry III left the safety of Lewes Castle and St. Pancras Priory to engage the barons in battle and was initially successful, his son Prince Edward routing part of the baronial army with a cavalry charge. However, Edward pursued his quarry off the battlefield and left Henry's men exposed. Henry was forced to launch an infantry attack up Offham Hill where he was defeated by the barons' men defending the hilltop. The royalists fled back to the castle and priory and the King was forced to sign the Mise of Lewes, ceding many of his powers to de Montfort.

The Battle of Evesham was one of the two main battles of 13th century England's Second Barons' War. It marked the defeat of Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, and the rebellious barons by the future King Edward I, who led the forces of his father, King Henry III. It took place on 4 August 1265, near the town of Evesham, Worcestershire.

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised the English monarch. Great councils were first called Parliaments during the reign of Henry III. By this time, the king required Parliament's consent to levy taxation.

Edmund, 1st Earl of Lancaster, also known by his epithet Edmund Crouchback, was a member of the royal Plantagenet Dynasty and the founder of the first House of Lancaster. He was Earl of Leicester (1265–1296), Lancaster (1267–1296) and Derby (1269–1296) in England, and Count Palatine of Champagne (1276–1284) in France.

John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey was a prominent English nobleman and military commander during the reigns of Henry III of England and Edward I of England. During the Second Barons' War he switched sides twice, ending up in support of the king, for whose capture he was present at Lewes in 1264. Warenne was later appointed as "warden of the kingdom and land of Scotland" and featured prominently in Edward I's wars in Scotland.

Eleanor of England was the youngest child of John, King of England and Isabella of Angoulême.

The Provisions of Oxford were constitutional reforms developed during the Oxford Parliament of 1258 to resolve a dispute between King Henry III of England and his barons. The reforms were designed to ensure the king adhered to the rule of law and governed according to the advice of his barons. A council of fifteen barons was chosen to advise and control the king and supervise his ministers. Parliament was to meet regularly three times a year.

Humphrey (VI) de Bohun, 3rd Earl of Hereford and 2nd Earl of Essex, was an English nobleman known primarily for his opposition to King Edward I over the Confirmatio Cartarum. He was also an active participant in the Welsh Wars and maintained for several years a private feud with the earl of Gloucester. His father, Humphrey (V) de Bohun, fought on the side of the rebellious barons in the Barons' War. When Humphrey (V) predeceased his father, Humphrey (VI) became heir to his grandfather, Humphrey (IV). At Humphrey (IV)'s death in 1275, Humphrey (VI) inherited the earldoms of Hereford and Essex. He also inherited major possessions in the Welsh Marches from his mother, Eleanor de Braose.

The Second Barons' War (1264–1267) was a civil war in England between the forces of a number of barons led by Simon de Montfort against the royalist forces of King Henry III, led initially by the king himself and later by his son, the future King Edward I. The barons sought to force the king to rule with a council of barons, rather than through his favourites. The war also involved a series of massacres of Jews by de Montfort's supporters, including his sons Henry and Simon, in attacks aimed at seizing and destroying evidence of baronial debts. To bolster the initial success of his baronial regime, de Montfort sought to broaden the social foundations of parliament by extending the franchise to the commons for the first time. However, after a rule of just over a year, de Montfort was killed by forces loyal to the king at the Battle of Evesham.

Hugh le Despenser, 1st Baron le Despenser was an important ally of Simon de Montfort during the reign of Henry III. He served briefly as Justiciar of England in 1260 and as Constable of the Tower of London.

Henry of Almain, also called Henry of Cornwall, was the eldest son of Richard, Earl of Cornwall, afterwards King of the Romans, by his first wife Isabel Marshal. His surname is derived from a vowel shift in pronunciation of d'Allemagne ; he was so called by the elites of England because of his father's status as the elected German King of Almayne.

Simon de Montfort's Parliament was an English parliament held from 20 January 1265 until mid-March of the same year, called by Simon de Montfort, a baronial rebel leader.

Events from the 1260s in England.

The Mise of Amiens was a settlement given by King Louis IX of France on 23 January 1264 in the conflict between King Henry III of England and his rebellious barons, led by Simon de Montfort. Louis' one-sided decision for King Henry led directly to the hostilities of the Second Barons' War.

The Mise of Lewes was a settlement made on 14 May 1264 between King Henry III of England and his rebellious barons, led by Simon de Montfort. The settlement was made on the day of the Battle of Lewes, one of the two major battles of the Second Barons' War. The conflict between king and magnates was caused by dissatisfaction with the influence of foreigners at court and Henry's high level and new methods of taxation. In 1258 Henry had been forced to accept the Provisions of Oxford, which essentially left the royal government in the hands of a council of magnates, but this document went through a long series of revocations and reinstatements. In 1263, as the country was on the brink of civil war, the two parties had agreed to submit the matter to arbitration by the French king Louis IX. Louis was a firm believer in the royal prerogative, and decided clearly in favour of Henry. The outcome was unacceptable for the rebellious barons, and war between the two parties broke out almost immediately.

During the Second Barons' War, the Peace of Canterbury was an agreement reached between the baronial government led by Simon de Montfort on one hand, and Henry III of England and his son and heir Edward – the later King Edward I – on the other. The agreement was signed at Canterbury some time between 12 and 15 August 1264.