The Inca Empire, called Tawantinsuyu by its subjects, was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political, and military center of the empire was in the city of Cusco. The Inca civilization rose from the Peruvian highlands sometime in the early 13th century. The Spanish began the conquest of the Inca Empire in 1532 and by 1572, the last Inca state was fully conquered.

Viracocha is the great creator deity in the pre-Inca and Inca mythology in the Andes region of South America. According to the myth Viracocha had human appearance and was generally considered as bearded. According to the myth he ordered the construction of Tiwanaku. It is also said that he was accompanied by men also referred to as Viracochas.

Manco Cápac, also known as Manco Inca and Ayar Manco, was, according to some historians, the first governor and founder of the Inca civilization in Cusco, possibly in the early 13th century. He is also a main figure of Inca mythology, being the protagonist of the two best known legends about the origin of the Inca, both of them connecting him to the foundation of Cusco. His main wife was his older sister, Mama Uqllu, also the mother of his son and successor Sinchi Ruq'a. Even though his figure is mentioned in several chronicles, his actual existence remains uncertain.

In the Quechua, Aymara, and Inca mythologies, Supay was both the god of death and ruler of the Ukhu Pacha, the Incan underworld, as well as a race of demons. Supay is associated with miners' rituals.

The Aymara or Aimara people are an indigenous people in the Andes and Altiplano regions of South America; about 2.3 million live in northwest Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. Their ancestors lived in the region for many centuries before becoming a subject people of the Inca in the late 15th or early 16th century, and later of the Spanish in the 16th century. With the Spanish-American wars of independence (1810–1825), the Aymaras became subjects of the new nations of Bolivia and Peru. After the War of the Pacific (1879–1883), Chile annexed territory with the Aymara population.

Andean music is a group of styles of music from the Andes region in South America.

The ayllu, a family clan, is the traditional form of a community in the Andes, especially among Quechuas and Aymaras. They are an indigenous local government model across the Andes region of South America, particularly in Bolivia and Peru.

The Inca religion was a group of beliefs and rites that were related to a mythological system evolving from pre-Inca times to Inca Empire. Faith in the Tawantinsuyu was manifested in every aspect of his life, work, festivities, ceremonies, etc. They were polytheists and there were local, regional and pan-regional divinities.

Pacha Kamaq was the deity worshipped in the city of Pachacamac by the Ichma.

Mother Nature is a personification of nature that focuses on the life-giving and nurturing aspects of nature by embodying it, in the form of the mother.

Quechua people or Quichua people may refer to any of the indigenous peoples of South America who speak the Quechua languages, which originated among the Indigenous people of Peru. Although most Quechua speakers are native to Peru, there are some significant populations in Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, and Argentina.

The Inti Raymi is a traditional religious ceremony of the Inca Empire in honor of the god Inti, the most venerated deity in Inca religion. It was the celebration of the winter solstice – the shortest day of the year in terms of the time between sunrise and sunset – and the Inca New Year, when the hours of light would begin to lengthen again. In territories south of the equator, the Gregorian months of June and July are winter months. It is held on June 24.

Sukay is an Andean folk music band.

Inti is the ancient Inca sun god. He is revered as the national patron of the Inca state. Although most consider Inti the sun god, he is more appropriately viewed as a cluster of solar aspects, since the Inca divided his identity according to the stages of the sun. Worshiped as a patron deity of the Inca Empire, Pachacuti is often linked to the origin and expansion of the Inca Sun Cult. The most common belief was that Inti was born of Viracocha, who had many titles, chief among them being the God of Creation.

Q'ero is a Quechua-speaking community or ethnic group dwelling in the province of Paucartambo, in the Cusco Region of Peru.

In the ancient religion and mythology of Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia, an apu is the term used to describe the spirits of mountains and sometimes solitary rocks, typically displaying anthropomorphic features, that protect the local people. The term dates back to the Inca Empire.

Inca mythology is the universe of legends and collective memory of the Inca civilization, which took place in the current territories of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina, incorporating in the first instance, systematically, the territories of the central highlands of Peru to the north.

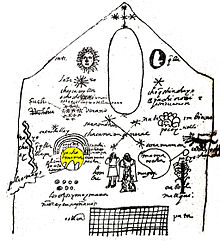

The pacha was an Incan concept for dividing the different spheres of the cosmos in Incan mythology. There were three different levels of pacha: the hana pacha, hanan pacha or hanaq pacha, ukhu pacha, and kay pacha. The realms are not solely spatial, but were simultaneously spatial and temporal. Although the universe was considered a unified system within Incan cosmology, the division between the worlds was part of the dualism prominent in Incan beliefs, known as Yanantin. This dualism found that everything which existed had both features of any feature.

Pachamama is a goddess revered by the indigenous people of the Andes.

Mama Quilla, in Inca mythology and religion, was the third power and goddess of the moon. She was the older sister and wife of Inti, daughter of Viracocha and mother of Manco Cápac and Mama Uqllu (Mama Ocllo), mythical founders of the Inca empire and culture. She was the goddess of marriage and the menstrual cycle, and considered a defender of women. She was also important for the Inca calendar.