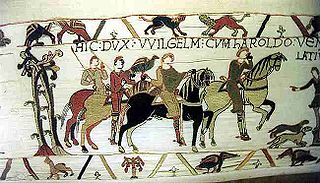

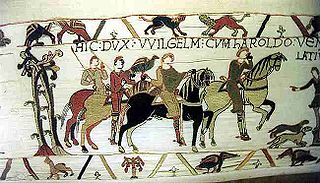

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity.

Chivalry, or the chivalric language, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It is associated with the medieval Christian institution of knighthood, with knights being members of various chivalric orders, and with knights' and gentlemen's behaviours which were governed by chivalrous social codes. The ideals of chivalry were popularized in medieval literature, particularly the literary cycles known as the Matter of France, relating to the legendary companions of Charlemagne and his men-at-arms, the paladins, and the Matter of Britain, informed by Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, written in the 1130s, which popularized the legend of King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table.

In later Anglo-Saxon England, a thegn or thane was an aristocrat who ranked at the third level in lay society, below the king and ealdormen. He had to be a substantial landowner. Thanage refers to the tenure by which lands were held by a thane as well as the rank.

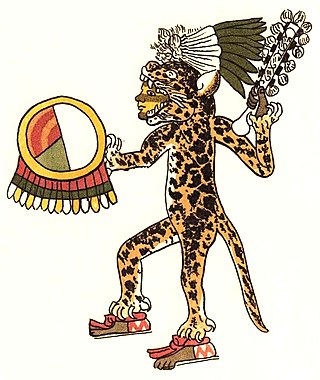

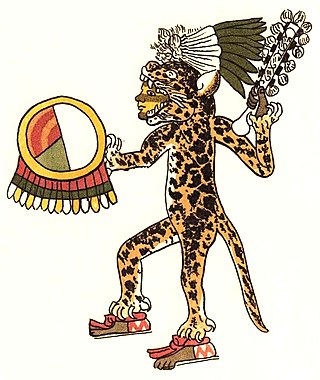

Jaguar warriors or jaguar knights, ocēlōtlNahuatl pronunciation:[oˈseːloːt͡ɬ] (singular) or ocēlōmeh (plural) were members of the Aztec military elite. They were a type of Aztec warrior called a cuāuhocēlōtl (derived from cuāuhtli and ocēlōtl. They were an elite military unit similar to the eagle warriors.

A valet or varlet is a male servant who serves as personal attendant to his employer. In the Middle Ages and Ancien Régime, valet de chambre was a role for junior courtiers and specialists such as artists in a royal court, but the term "valet" by itself most often refers to a normal servant responsible for the clothes and personal belongings of an employer, and making minor arrangements. In the United States, the term most often refers to a parking valet, and the role is often confused with a butler.

Ghilman were slave-soldiers and/or mercenaries in armies throughout the Islamic world. Islamic states from the early 9th century to the early 19th century consistently deployed slaves as soldiers, a phenomenon that was very rare outside of the Islamic world.

In the Middle Ages, a squire was the shield- or armour-bearer of a knight.

Book of the Civilized Man, by Daniel of Beccles, is believed to be the first English courtesy book, dating probably from the beginning of the 13th century. The book is significant because in the later Middle Ages dozens of such courtesy books were produced. Because this appears to be the first in English history, it represented a new awakening to etiquette and decorum in English court society, which occurred in the 13th century. As a general rule, a book of etiquette is a mark of a dynamic rather than a stable society, one in which there is an influx of "new" men, who have not been indoctrinated with the correct decorum from an early age and who are avid to catch up in a hurry.

Royal hunting, also royal art of hunting, was a hunting practice of the aristocracy throughout the known world in the Middle Ages, from Europe to Far East. While humans hunted wild animals since time immemorial, and all classes engaged in hunting as an important source of food and at times the principal source of nutrition, the necessity of hunting was transformed into a stylized pastime of the aristocracy. In Europe in the High Middle Ages the practice was widespread.

The aristocracy of Norway is the modern and medieval aristocracy in Norway. Additionally, there have been economical, political, and military elites that—relating to the main lines of Norway's history—are generally accepted as nominal predecessors of the aforementioned. Since the 16th century, modern aristocracy is known as nobility.

1840s fashion in European and European-influenced clothing is characterized by a narrow, natural shoulder line following the exaggerated puffed sleeves of the later 1820s and 1830s. The narrower shoulder was accompanied by a lower waistline for both men and women.

Fashion in the period 1700–1750 in European and European-influenced countries is characterized by a widening silhouette for both men and women following the tall, narrow look of the 1680s and 90s. This era is defined as late Baroque/Rococo style. The new fashion trends introduced during this era had a greater impact on society, affecting not only royalty and aristocrats, but also middle and even lower classes. Clothing during this time can be characterized by soft pastels, light, airy, and asymmetrical designs, and playful styles. Wigs remained essential for men and women of substance, and were often white; natural hair was powdered to achieve the fashionable look. The costume of the eighteenth century, if lacking in the refinement and grace of earlier times, was distinctly quaint and picturesque.

Primary education is typically the first stage of formal education, coming after preschool/kindergarten and before secondary school. Primary education takes place in primary schools, elementary schools, or first schools and middle schools, depending on the location. Hence, in the United Kingdom and some other countries, the term primary is used instead of elementary.

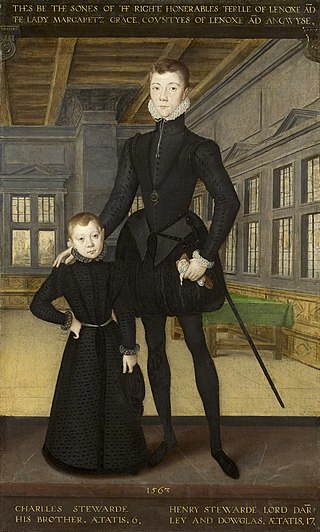

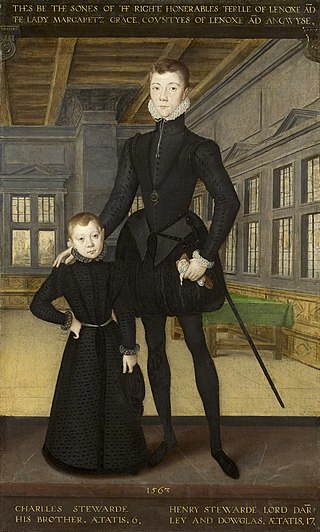

Breeching was the occasion when a small boy was first dressed in breeches or trousers. From the mid-16th century until the late 19th or early 20th century, young boys in the Western world were unbreeched and wore gowns or dresses until an age that varied between two and eight. Various forms of relatively subtle differences usually enabled others to tell depictions of little boys from those of little girls, in codes that modern art historians are able to understand but may be difficult for the layperson to discern.

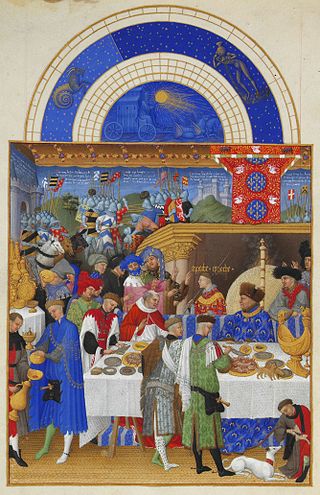

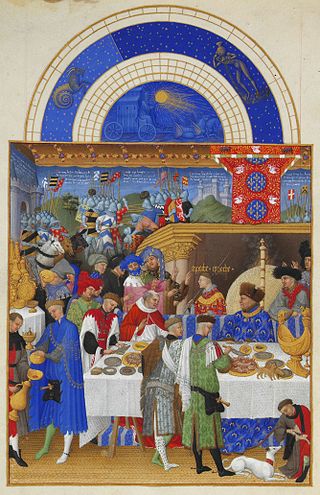

The medieval household was, like modern households, the center of family life for all classes of European society. Yet in contrast to the household of today, it consisted of many more individuals than the nuclear family. From the household of the king to the humblest peasant dwelling, more or less distant relatives and varying numbers of servants and dependents would cohabit with the master of the house and his immediate family. The structure of the medieval household was largely dissolved by the advent of privacy in early modern Europe.

Women in the Middle Ages in Europe occupied a number of different social roles. Women held the positions of wife, mother, peasant, warrior, artisan, and nun, as well as some important leadership roles, such as abbess or queen regnant. The very concept of women changed in a number of ways during the Middle Ages, and several forces influenced women's roles during this period, while also expanding upon their traditional roles in society and the economy. Whether or not they were powerful or stayed back to take care of their homes, they still played an important role in society whether they were saints, nobles, peasants, or nuns. Due to context from recent years leading to the reconceptualization of women during this time period, many of their roles were overshadowed by the work of men. Although it is prevalent that women participated in church and helping at home, they did much more to influence the Middle Ages.

Childhood in early modern Scotland includes all aspects of the lives of children, from birth to adulthood, between the early sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth century. This period corresponds to the early modern period in Europe, beginning with the Renaissance and Reformation and ending with the beginning of industrialisation and the Enlightenment in the mid-eighteenth century.

Childhood in Medieval Scotland includes all aspects of childhood within the geographical area that became the Kingdom of Scotland, from the end of Roman power in Great Britain, until the Renaissance and Reformation in the sixteenth century.

In Viking Age Scandinavia, boys were legally considered to be adults at age 16. But before they reached adulthood, they had a childhood spent learning the skills they would need to be successful. Viking children were primarily raised by their mothers, although sometimes Viking boys lived with another family for a period of time as a foster child. This was meant to forge bonds between the two families and entitled the boy to help from his foster family, as well as his birth family. It also bound him to them and they often remained close through the life of the boy.