Calotype or talbotype is an early photographic process introduced in 1841 by William Henry Fox Talbot, using paper coated with silver iodide. Paper texture effects in calotype photography limit the ability of this early process to record low contrast details and textures. The term calotype comes from the Ancient Greek καλός, "beautiful", and τύπος, "impression".

William Henry Fox Talbot FRS FRSE FRAS was an English scientist, inventor, and photography pioneer who invented the salted paper and calotype processes, precursors to photographic processes of the later 19th and 20th centuries. His work in the 1840s on photomechanical reproduction led to the creation of the photoglyphic engraving process, the precursor to photogravure. He was the holder of a controversial patent that affected the early development of commercial photography in Britain. He was also a noted photographer who contributed to the development of photography as an artistic medium. He published The Pencil of Nature (1844–1846), which was illustrated with original salted paper prints from his calotype negatives and made some important early photographs of Oxford, Paris, Reading, and York.

The collodion process is an early photographic process. The collodion process, mostly synonymous with the "collodion wet plate process", requires the photographic material to be coated, sensitized, exposed, and developed within the span of about fifteen minutes, necessitating a portable darkroom for use in the field. Collodion is normally used in its wet form, but it can also be used in its dry form, at the cost of greatly increased exposure time. The increased exposure time made the dry form unsuitable for the usual portraiture work of most professional photographers of the 19th century. The use of the dry form was mostly confined to landscape photography and other special applications where minutes-long exposure times were tolerable.

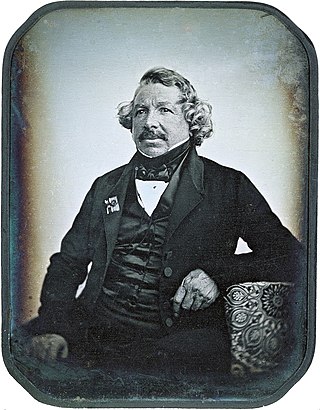

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre was a French artist and photographer, recognized for his invention of the eponymous daguerreotype process of photography. He became known as one of the fathers of photography. Though he is most famous for his contributions to photography, he was also an accomplished painter, scenic designer, and a developer of the diorama theatre.

The albumen print, also called albumen silver print, was published in January 1847 by Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard, and was the first commercially exploitable method of producing a photographic print on a paper base from a negative. It used the albumen found in egg whites to bind the photographic chemicals to the paper and became the dominant form of photographic positives from 1855 to the start of the 20th century, with a peak in the 1860–90 period. During the mid-19th century, the carte de visite became one of the more popular uses of the albumen method. In the 19th century, E. & H. T. Anthony & Company were the largest makers and distributors of albumen photographic prints and paper in the United States.

The gelatin silver process is the most commonly used chemical process in black-and-white photography, and is the fundamental chemical process for modern analog color photography. As such, films and printing papers available for analog photography rarely rely on any other chemical process to record an image. A suspension of silver salts in gelatin is coated onto a support such as glass, flexible plastic or film, baryta paper, or resin-coated paper. These light-sensitive materials are stable under normal keeping conditions and are able to be exposed and processed even many years after their manufacture. The "dry plate" gelatin process was an improvement on the collodion wet-plate process dominant from the 1850s–1880s, which had to be exposed and developed immediately after coating.

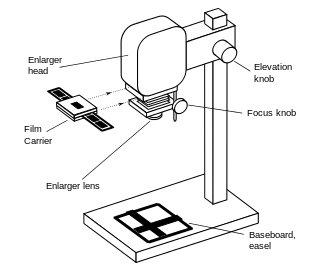

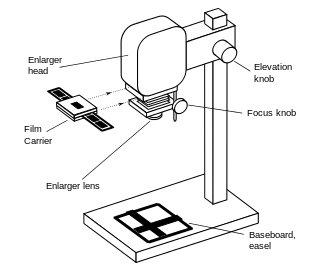

An enlarger is a specialized transparency projector used to produce photographic prints from film or glass negatives, or from transparencies.

Frederick Scott Archer was an English photographer and sculptor who is best known for having invented the photographic collodion process which preceded the modern gelatin emulsion. He was born in either Bishop's Stortford or Hertford, within the county of Hertfordshire, England and is remembered mainly for this single achievement which greatly increased the accessibility of photography for the general public.

The ambrotype also known as a collodion positive in the UK, is a positive photograph on glass made by a variant of the wet plate collodion process. Like a print on paper, it is viewed by reflected light. Like the daguerreotype, which it replaced, and like the prints produced by a Polaroid camera, each is a unique original that could only be duplicated by using a camera to copy it.

A tintype, also known as a melanotype or ferrotype, is a photograph made by creating a direct positive on a thin sheet of metal, colloquially called 'tin', coated with a dark lacquer or enamel and used as the support for the photographic emulsion. It was introduced in 1853 by Adolphe Alexandre Martin in Paris, like the daguerreotype was fourteen years before by Daguerre. The daguerreotype was established and most popular by now, though the primary competition for the tintype would have been the ambrotype, that shared the same collodion process, but on a glass support instead of metal. Both found unequivocal, if not exclusive, acceptance in North America. Tintypes enjoyed their widest use during the 1860s and 1870s, but lesser use of the medium persisted into 1930s and it has been revived as a novelty and fine art form in the 21st century. It has been described as the first "truly democratic" medium for mass portraiture.

Heliography from helios, meaning "sun", and graphein (γράφειν), "writing") is the photographic process invented, and named thus, by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce around 1822, which he used to make the earliest known surviving photograph from nature, View from the Window at Le Gras, and the first realisation of photoresist as means to reproduce artworks through inventions of photolithography and photogravure.

The history of photography began with the discovery of two critical principles: camera obscura image projection and the observation that some substances are visibly altered by exposure to light. There are no artifacts or descriptions that indicate any attempt to capture images with light sensitive materials prior to the 18th century.

The paper negative process consists of using a negative printed on paper to create the final print of a photograph, as opposed to using a modern negative on a film base of cellulose acetate. The plastic acetate negative enables the printing of a very sharp image intended to be as close a representation of the actual subject as is possible. By using a negative based on paper instead, there is the possibility of creating a more ethereal image, simply by using a type of paper with a very visible grain, or by drawing on the paper or distressing it in some way.

Photozincography, sometimes referred to as heliozincography but essentially the same process, known commercially as zinco, is the photographic process developed by Sir Henry James FRS (1803–1877) in the mid-nineteenth century.

Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard was a French inventor, photographer and photo publisher. Being a cloth merchant by trade, in the 1840s he developed interest in photography and focused on technical and economical issues of mass production of photo prints.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to photography:

Peter Wickens Fry was a pioneering English amateur photographer, although professionally he was a London solicitor. In the early 1850s, Fry worked with Frederick Scott Archer, assisting him in the early experiments of the wet collodion process. He was also active in helping Roger Fenton to set up the Royal Photographic Society in 1853. Several of his photographs are in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

The conservation and restoration of photographic plates is caring for and maintaining photographic plates to preserve their materials and content. It covers the necessary measures that can be taken by conservators, curators, collection managers, and other professionals to conserve the material unique to photographic plate processes. This practice includes understanding the composition and agents of deterioration of photographic plates, as well as the preventive conservation and interventive conservation measures that can be taken to increase their longevity.

Photo-crayotypes were an artistic process used for the hand-colouring of photographs by the application of crayons and pigments over a photographic impression.

Hugh Owen was one of the first generation of amateur photographers in the United Kingdom.