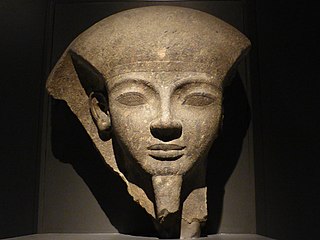

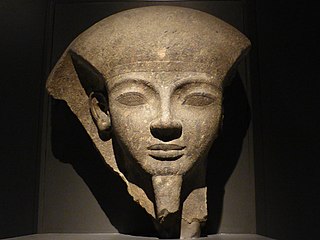

Neferkare Setepenre Ramesses IX was the eighth pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt. He was the third longest serving king of this Dynasty after Ramesses III and Ramesses XI. He is now believed to have assumed the throne on I Akhet day 21 based on evidence presented by Jürgen von Beckerath in a 1984 GM article. According to the latest archaeological information, Ramesses IX died in Regnal Year 19 I Peret day 27 of his reign. Therefore, he enjoyed a reign of 18 years, 4 months and 6 days. His throne name, Neferkare Setepenre, means "Beautiful Is The Soul of Re, Chosen of Re." Ramesses IX is believed to be the son of Mentuherkhepeshef, a son of Ramesses III, since Mentuherkhopshef's wife, the lady Takhat bears the prominent title of King's Mother on the walls of tomb KV10, which she usurped and reused in the late 20th Dynasty; no other 20th Dynasty king is known to have had a mother with this name. Ramesses IX was, therefore, probably a grandson of Ramesses III.

Usermaatre Heqamaatre Setepenamun Ramesses IV was the third pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt. He was the second son of Ramesses III and became crown prince when his elder brother Amenherkhepshef died aged 15 in 1164 BC, when Ramesses was only 12 years old. His promotion to crown prince:

is suggested by his appearance in a scene of the festival of Min at the Ramesses III temple at Karnak, which may have been completed by Year 22 [of his father's reign].

Userkhaure-setepenre Setnakhte was the first pharaoh (1189 BC–1186 BC) of the Twentieth Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt and the father of Ramesses III.

Khepermaatre Ramesses X was the ninth pharaoh of the 20th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. His birth name was Amonhirkhepeshef. His prenomen or throne name, Khepermaatre, means "The Justice of Re Abides."

Menmaatre Ramesses XI reigned from 1107 BC to 1078 BC or 1077 BC and was the tenth and final pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt and as such, was the last king of the New Kingdom period. He ruled Egypt for at least 29 years although some Egyptologists think he could have ruled for as long as 30. The latter figure would be up to 2 years beyond this king's highest known date of Year 10 of the Whm Mswt era or Year 28 of his reign. One scholar, Ad Thijs, has suggested that Ramesses XI could even have reigned as long as 33 years.

Ramesses VI Nebmaatre-Meryamun was the fifth ruler of the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt. He reigned for about eight years in the mid-to-late 12th century BC and was a son of Ramesses III and queen Iset Ta-Hemdjert. As a prince, he was known as Ramesses Amunherkhepeshef and held the titles of royal scribe and cavalry general. He was succeeded by his son, Ramesses VII Itamun, whom he had fathered with queen Nubkhesbed.

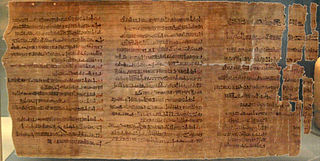

Usermaatre Setepenre Meryamun Ramesses VII was the sixth pharaoh of the 20th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. He reigned from about 1136 to 1129 BC and was the son of Ramesses VI. Other dates for his reign are 1138–1131 BC. The Turin Accounting Papyrus 1907+1908 is dated to Year 7 III Shemu day 26 of his reign and has been reconstructed to show that 11 full years passed from Year 5 of Ramesses VI to Year 7 of his reign.

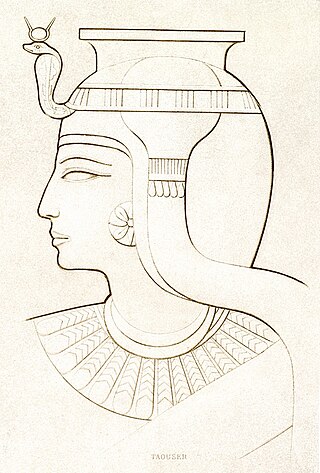

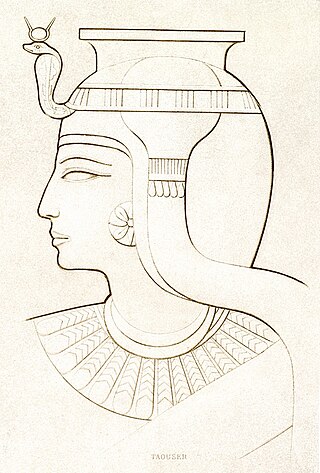

Tausret, also spelled Tawosret or Twosret was the last known ruler and the final pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt.

Tomb KV2, found in the Valley of the Kings, is the tomb of Ramesses IV, and is located low in the main valley, between KV7 and KV1. It has been open since antiquity and contains a large amount of graffiti.

Tomb ANB is a sepulchre located in the west of the necropolis of Dra' Abu el-Naga', near Thebes, Egypt. It may well have been intended as the burial place of the 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Amenhotep I and his mother Ahmose-Nefertari.

Nubkheperre Intef was an Egyptian king of the Seventeenth Dynasty of Egypt at Thebes during the Second Intermediate Period, when Egypt was divided by rival dynasties including the Hyksos in Lower Egypt.

The Valley of the Kings, also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings, is an area in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the Eighteenth Dynasty to the Twentieth Dynasty, rock-cut tombs were excavated for pharaohs and powerful nobles under the New Kingdom of ancient Egypt.

Sekhemre Shedtawy Sobekemsaf II was an Egyptian king who reigned during the Second Intermediate Period, when Egypt was fragmented and ruled by multiple kings.

The period of ancient Egyptian history known as wehem mesut or, more commonly, Whm Mswt can be literally translated as Repetition of Births, but is usually referred to as the (Era of the) Renaissance.

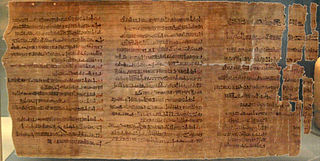

The Abbott Papyrus serves as an important political document concerning the tomb robberies of the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt during the New Kingdom. It also gives insight into the scandal between the two rivals Pawero and Paser of Thebes.

The Mayer Papyri are two ancient Egyptian documents from the Twentieth Dynasty that contain records of court proceedings, now held at the World Museum in Liverpool, England.

Tyti was an ancient Egyptian queen of the 20th Dynasty. A wife and sister of Ramesses III and possibly the mother of Ramesses IV.

The Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt is the third and last dynasty of the Ancient Egyptian New Kingdom period, lasting from 1189 BC to 1077 BC. The 19th and 20th Dynasties together constitute an era known as the Ramesside period owing to the predominance of rulers with the given name "Ramesses". This dynasty is generally considered to mark the beginning of the decline of Ancient Egypt at the transition from the Late Bronze to Iron Age. During the period of the Twentieth Dynasty, Ancient Egypt faced the crisis of invasions by Sea Peoples. The dynasty successfully defended Egypt, while sustaining heavy damage.

Khaemwaset was an ancient Egyptian vizier of the South, governor of Thebes, and possibly also High Priest of Ptah during the reign of pharaohs Ramesses IX of the 20th Dynasty.

He is mainly known for being the vizier who ordered and led the investigation into the royal tomb robberies which occurred under Ramesses IX.

Papyrus Ambras is a papyrus which was formerly in the collection of Ambras Castle near Inssbruck, and is now a part of the collection of the Vienna Museum. The first to draw attention to it was the Egyptologist Heinrich Karl Brugsch, who published about it in 1876.