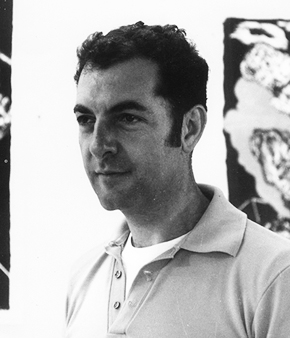

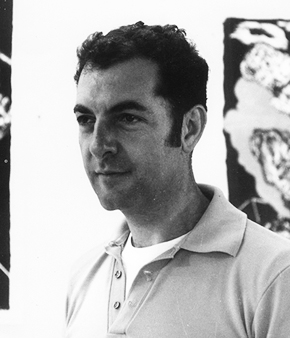

Leon Golub was an American painter. He was born in Chicago, Illinois, where he also studied, receiving his BA at the University of Chicago in 1942, and his BFA and MFA at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1949 and 1950, respectively.

Karl Wirsum was an American artist. He was a member of the Chicago artistic group The Hairy Who, and helped set the foundation for Chicago's art scene in the 1970s. Although he was primarily a painter, he also worked with prints, sculpture, and even digital art.

Roger Brown was an American artist and painter. Often associated with the Chicago Imagist groups, he was internationally known for his distinctive painting style and shrewd social commentaries on politics, religion, and art.

The Chicago Imagists are a group of representational artists associated with the School of the Art Institute of Chicago who exhibited at the Hyde Park Art Center in the late 1960s.

Barbara Rossi is a Chicago-based artist, one of the original Chicago Imagists, a group that in the 1960s and 1970s turned to representational art. She first exhibited with them at the Hyde Park Art Center in 1969. She is known for meticulously rendered drawings and cartoonish paintings, as well as a personal vernacular. She works primarily by making reverse paintings on plexiglass that reference lowbrow and outsider art.

Cosmo Campoli was a Chicago-based sculptor, known for his figurative work centered on the themes of birth and death, and for his use of bold, surreal bird and egg imagery. He was a member of a group of School of the Art Institute of Chicago artists collectively dubbed the "Monster Roster" by critic Franz Schulze in the late 1950s, based on their affinity for sometimes gruesome, expressive figuration, fantasy and mythology, and existential thought. That group included, among others, Leon Golub, George Cohen, June Leaf, H.C. Westermann, Seymour Rosofsky, and Theodore Halkin. Campoli rose to prominence in the 1950s locally and nationally when art historian and curator Peter Selz featured him, Golub and Cohen in a 1955 ARTnews article, "Is There a New Chicago School?", and included him, Golub and Westermann in the 1959 Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) exhibition, New Images of Man, as examples of vanguard expressive figurative work in Europe and the United States. Campoli's work was also shown at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Smart Museum of Art, Beloit College, the Hyde Park Art Center, and in a career retrospective at Chicago's Museum of Contemporary Art in 1971. Campoli was hampered in later years by bipolar disorder.

Visual arts of Chicago refers to paintings, prints, illustrations, textile art, sculpture, ceramics and other visual artworks produced in Chicago or by people with a connection to Chicago. Since World War II, Chicago visual art has had a strong individualistic streak, little influenced by outside fashions. "One of the unique characteristics of Chicago," said Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts curator Bob Cozzolino, "is there's always been a very pronounced effort to not be derivative, to not follow the status quo." The Chicago art world has been described as having "a stubborn sense ... of tolerant pluralism." However, Chicago's art scene is "critically neglected." Critic Andrew Patner has said, "Chicago's commitment to figurative painting, dating back to the post-War period, has often put it at odds with New York critics and dealers." It is argued that Chicago art is rarely found in Chicago museums; some of the most remarkable Chicago artworks are found in other cities.

Raymond "Ray" Kakuo Yoshida was an American artist known for his paintings and collages, and for his contributions as a teacher at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago from 1959 to 2005. He was an important mentor of the Chicago Imagists, a group in the 1960s and 1970s who specialized in distorted, emotional representational art.

Suellen Rocca was an American artist, one of the original Chicago Imagists, a group in the 1960s and 1970s who turned to representational art. She exhibited with them at the Hyde Park Art Center from 1966 through 1969. She was curator of the art collection and director of exhibitions at Elmhurst College.

Phyllis Bramson is an American artist, based in Chicago and known for "richly ornamental, excessive and decadent" paintings described as walking a tightrope between "edginess and eroticism." She combines eclectic influences, such as kitsch culture, Rococo art and Orientalism, in juxtapositions of fantastical figures, decorative patterns and objects, and pastoral landscapes that affirm the pleasures and follies of romantic desire, imagination and looking. Bramson shares tendencies with the Chicago Imagists and broader Chicago tradition of surreal representation in her use of expressionist figuration, vernacular culture, bright color, and sexual imagery. Curator Lynne Warren wrote of her 30-year retrospective at the Chicago Cultural Center, "Bramson passionately paints from her center, so uniquely shaped in her formative years […] her lovely colors, fluttery, vignette compositions, and flowery and cartoony imagery create works that are really like no one else's. Writer Miranda McClintic said that Bramson's works "incorporate the passionate complexity of eastern mythology, the sexual innuendos of soap operas and sometimes the happy endings of cartoons." Bramson's work has been exhibited in exhibitions and surveys at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (MCA), the Art Institute of Chicago, the Smithsonian Institution, and Corcoran Gallery of Art. In more than forty one-person exhibitions, she has shown at the New Museum, Fort Wayne Museum of Art, Boulder Art Museum, University of West Virginia Museum, and numerous galleries. She has been widely reviewed and recognized with John S. Guggenheim and Rockefeller foundation grants and the Anonymous Was A Woman Award, among others. She was one of the founding members of the early women's art collaborative Artemisia Gallery and a long-time professor at the School of Art and Design at the University of Illinois at Chicago, until retiring in 2007.

Christina Ramberg was an American painter associated with the Chicago Imagists, a group of representational artists who attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the late 1960s. The Imagists took their cues from Surrealism, Pop, and West Coast underground comic illustration, and were "enchanted with the abject status of sex in post-war America, particularly as writ on the female form." Ramberg is best known for her depictions of partial female bodies forced into submission by undergarments and imagined in odd, erotic predicaments.

Richard Wetzel is an American artist. He is best known for his oil paintings but also has exhibited collages and sculpture. In 1969 and 1970, Wetzel exhibited with the Chicago Imagists, a grouping of Chicago artists who were ascendant in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Don Baum (1922–2008) was an American curator, artist and educator, most known as a key impresario and promoter of the Chicago Imagists, a group of artists that had an enduring impact on American art in the later twentieth century. Described by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (MCA) as "an indispensable curator of the Chicago school," Baum was known for lively and irreverent exhibitions that offered fresh perspectives combining elements of Surrealism and Pop and that broke down barriers between schooled and untrained, or so-called outsider artists. From 1956 to 1972, Baum was exhibitions director at Chicago's Hyde Park Art Center. It was there, in the 1960s, that he became involved with a group of young artists he exhibited as "Hairy Who" that later expanded to become the Chicago Imagists. That group included Ed Paschke, Jim Nutt, Roger Brown, Gladys Nilsson, and Karl Wirsum. Baum mounted two major shows at the MCA that featured the emerging artists in their first museum exhibitions: "Don Baum Sez: 'Chicago Needs Famous Artists'" (1969) and "Made in Chicago" (1973), which shaped a vision of Chicago's art world as a place of meticulous craftsmanship and vernacular inspiration.

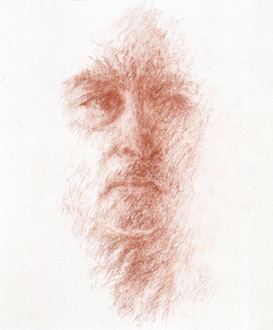

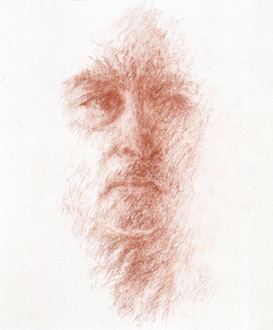

Arthur Lerner is an American artist, known for his atmospheric figurative paintings and drawings, landscapes, and still lifes. He is sometimes described as a realist, but most critics observe that his work is more subjective than descriptive or literal. Associated with Chicago's influential "Monster Roster" artists early in his career, he shared their enthusiasm for expressive figuration, fantasy and mythology, and their existential outlook, but diverged increasingly in his classical formal concerns and more detached temperament. Critics frequently note in Lerner's art a sense of light that evokes Impressionism, delicate color and modelling that "flirts with dematerialization," and the draftsmanship that serves as a foundation for all of his work. The Chicago Tribune's Alan Artner lamented Lerner's comparative lack of recognition in relation to the Chicago Imagists as the fate of "an aesthete in a town dominated by tenpenny fantasts." Lerner's work has been extensively covered in publications, featured in books such as Monster Roster: Existential Art in Postwar Chicago, and acquired by public and private collections, including those of the Smithsonian Institution, Art Institute of Chicago, Smart Museum of Art, and Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, among many.

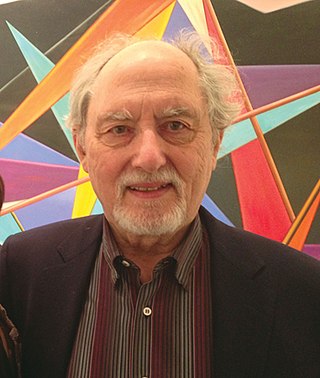

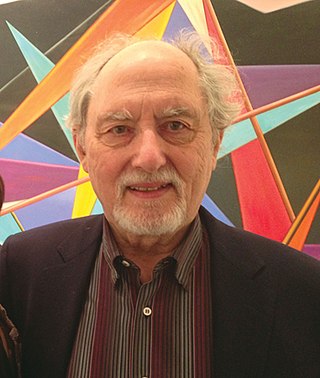

William Conger is a Chicago-based, American painter and educator, known for a dynamic, subjective style of abstraction descended from Kandinsky, which consciously employs illogical, illusionistic space and light and ambiguous forms that evoke metaphorical associations. He is a member of the "Allusive Abstractionists," an informal group of Chicago painters self-named in 1981, whose paradoxical styles countered the reductive minimalism that dominated post-1960s art. In 1982, critic Mary Mathews Gedo hailed them as "prescient prophets of the new style of abstraction" that flowered in the 1980s. In his essay for Conger's fifty-year career retrospective, Donald Kuspit called Conger art-historically daring for forging a path of subjective abstraction after minimalism had allegedly purged painting of an inner life. Despite being abstract, his work has a strong connection to Chicago's urban, lakeside geography and displays idiosyncratic variations of tendencies identified with Chicago Imagist art. A hallmark of Conger's career has been his enduring capacity for improvisation and discovery within self-prescribed stylistic limits.

Seymour Rosofsky was an American artist, who has been described as one of the key figures in twentieth-century Chicago art. He emerged in the late 1940s at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, one of several G.I. Bill veterans, including Leon Golub, Cosmo Campoli and H. C. Westermann, who would join Don Baum, Dominick Di Meo, June Leaf, and Nancy Spero to form the influential movement later dubbed the "Monster Roster" by critic Franz Schulze, which was a precursor to the more well-known Chicago Imagists. Like others in the group, Rosofsky was drawn to the unsettling, macabre side of Surrealism, initially creating gestural, expressionist renderings of grotesque, existentially angst-ridden figures in isolated or uncomfortable situations, that gave way in the 1960s to more fantastical, observational paintings that examined power, politics and domestic relationships in an unflinching way.

David Sharpe is an American artist, known for his stylized and expressionist paintings of the figure and landscape and for early works of densely packed, organic abstraction. He was trained at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and worked in Chicago until 1970, when he moved to New York City, where he remains. Sharpe has exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Art Institute of Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA), The Drawing Center, Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, Indianapolis Museum of Art, and Chicago Cultural Center, among many venues. His work has been reviewed in Art in America, ARTnews, Arts Magazine, New Art Examiner, the New York Times, and the Chicago Tribune, and been acquired by public institutions such as the Art Institute of Chicago, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, MCA Chicago, Smart Museum of Art, and Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, among many.

Robert Morris Donley is an American artist who has been identified with the Chicago Imagist movement. Judith Wilson of the Village Voice called him the "Chicago imagist Tolstoy." The narrative aspects of his work center on broad social and political statements that are complex--often playful and satirical with respect to ways in which propaganda, power, and social diversity mix with and conflict with historical and religious personalities. In his career retrospective in 2000 at the Chicago Cultural Center, Dr. Paul Jaskot wrote that "his art investigates the changing political and social geographies of [the modern] city."

Frank Piatek is an American artist, known for abstract, illusionistic paintings of tubular forms and three-dimensional works exploring spirituality, cultural memory and the creative process. Piatek emerged in the mid-1960s, among a group of Chicago artists exploring various types of organic abstraction that shared qualities with the Chicago Imagists; his work, however relies more on suggestion than expressionistic representation. In Art in Chicago 1945-1995, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (MCA) described Piatek as playing “a crucial role in the development and refinement of abstract painting in Chicago" with carefully rendered, biomorphic compositions that illustrate the dialectical relationship between Chicago's idiosyncratic abstract and figurative styles. Piatek's work has been exhibited at institutions including the Whitney Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, MCA Chicago, National Museum, Szczecin in Poland, and Terra Museum of American Art; it belongs to the public art collections of the Art Institute of Chicago and MCA Chicago, among others. Curator Lynne Warren describes Piatek as "the quintessential Chicago artist—a highly individualistic, introspective outsider" who has developed a "unique and deeply felt world view from an artistically isolated vantage point." Piatek lives and works in Chicago with his wife, painter and SAIC professor Judith Geichman, and has taught at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago since 1974.

Judy Ledgerwood is an American abstract painter and educator, who has been based in Chicago. Her work confronts fundamental, historical and contemporary issues in abstract painting within a largely high-modernist vocabulary that she often complicates and subverts. Ledgerwood stages traditionally feminine-coded elements—cosmetic and décor-related colors, references to ornamental and craft traditions—on a scale associated with so-called "heroic" abstraction; critics suggest her work enacts an upending or "domestication" of modernist male authority that opens the tradition to allusions to female sexuality, design, glamour and pop culture. Critic John Yau writes, "In Ledgerwood’s paintings the viewer encounters elements of humor, instances of surprise, celebrations of female sexuality, forms of vulgar tactility, and intense and unpredictable combinations of color. There is nothing formulaic about her approach."