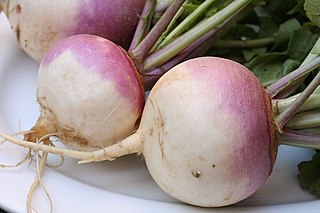

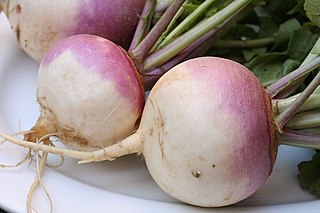

The turnip or white turnip is a root vegetable commonly grown in temperate climates worldwide for its white, fleshy taproot. The word turnip is a compound of turn as in turned/rounded on a lathe and neep, derived from Latin napus, the word for the plant. Small, tender varieties are grown for human consumption, while larger varieties are grown as feed for livestock. In Northern England, Scotland, Ireland, Cornwall and parts of Canada, the word turnip often refers to rutabaga, also known as swede, a larger, yellow root vegetable in the same genus (Brassica).

The sweet potato or sweetpotato is a dicotyledonous plant that belongs to the bindweed or morning glory family, Convolvulaceae. Its large, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a root vegetable. The young shoots and leaves are sometimes eaten as greens. Cultivars of the sweet potato have been bred to bear tubers with flesh and skin of various colors. Sweet potato is only distantly related to the common potato, both being in the order Solanales. Although darker sweet potatoes are often referred to as "yams" in parts of North America, the species is not a true yam, which are monocots in the order Dioscoreales.

Colocasia is a genus of flowering plants in the family Araceae, native to southeastern Asia and the Indian subcontinent. Some species are widely cultivated and naturalized in other tropical and subtropical regions.

Amelanchier, also known as shadbush, shadwood or shadblow, serviceberry or sarvisberry, juneberry, saskatoon, sugarplum, wild-plum or chuckley pear, is a genus of about 20 species of deciduous-leaved shrubs and small trees in the rose family (Rosaceae).

Root vegetables are underground plant parts eaten by humans as food. Although botany distinguishes true roots from non-roots, the term "root vegetable" is applied to all these types in agricultural and culinary usage.

Amelanchier alnifolia, the saskatoon berry, Pacific serviceberry, western serviceberry, western shadbush, or western juneberry, is a shrub with an edible berry-like fruit, native to North America.

Indigenous cuisine of the Americas includes all cuisines and food practices of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Contemporary Native peoples retain a varied culture of traditional foods, along with the addition of some post-contact foods that have become customary and even iconic of present-day Indigenous American social gatherings. Foods like cornbread, turkey, cranberry, blueberry, hominy and mush have been adopted into the cuisine of the broader United States population from Native American cultures.

Pachyrhizus erosus, commonly known as jícama or Mexican turnip, is the name of a native Mexican vine, although the name most commonly refers to the plant's edible tuberous root. It is in the pea family (Fabaceae). Pachyrhizus tuberosus and Pachyrhizus ahipa are the other two cultivated species in the genus. The naming of this group of edible plants can sometimes be confusing, with much overlap of similar or the same common names.

Yam is the common name for some plant species in the genus Dioscorea that form edible tubers. The tubers of some other species in the genus, such as D. communis, are toxic. Yams are perennial herbaceous vines cultivated for the consumption of their starchy tubers in many temperate and tropical regions, especially in West Africa, South America and the Caribbean, Asia, and Oceania. The tubers themselves, also called "yams", come in a variety of forms owing to numerous cultivars and related species.

Wild turnip is a common name for several plants and may refer to:

Tylosema esculentum, with common names gemsbok bean and marama bean or morama bean, is a long-lived perennial legume native to arid areas of southern Africa. Stems grow at least 3 metres (9.8 ft), in a prostrate or trailing form, with forked tendrils that facilitate climbing. A raceme up to 25 millimetres (1 in) long, containing many yellow-orange flowers, ultimately produces an ovate to circular pod, with large brownish-black seeds.

Pediomelum hypogaeum is a perennial herb also known as the little Indian breadroot or subterranean Indian breadroot. It is found on the black soil prairies in Texas.

Pediomelum cuspidatum is a perennial herb also known as the buffalo pea, largebract Indian breadroot and the tall-bread scurf-pea. It is found on the black soil prairies in Texas. It has an inflorescence on stems 18-40 centimeters long arising from a subterranean stem and deep carrot-shaped root that is 4–15 cm long. The long petioled leaves are palmately divided into 5 linear-elliptic leaflets that are 2-4 centimeters long. The flowers, borne in condensed spikes from the leaves, are light blue and pea-like.

Pediomelum is a genus of legumes known as Indian breadroots. These are glandular perennial plants with palmately-arranged leaves. They have a main erect stem with inflorescences of blue or purple flowers and produce hairy legume pods containing beanlike seeds. Some species have woody roots while others have starchy tuber-like roots which can be eaten like tuber vegetables such as potatoes or made into flour. Indian breadroots are native to North America. Many species have synonymy with genus Psoralea.

P. esculenta may refer to:

Agriculture on the precontact Great Plains describes the agriculture of the Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains of the United States and southern Canada in the Pre-Columbian era and before extensive contact with European explorers, which in most areas occurred by 1750. The principal crops grown by Indian farmers were maize (corn), beans, and squash, including pumpkins. Sunflowers, goosefoot, tobacco, gourds, and plums, were also grown.

Pleasant Valley Conservancy is a Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources-dedicated State Natural Area. The area contains a variety of natural communities found in Wisconsin including oak woodland, oak savanna, dry and wet prairies, sedge meadow, shrub-carr, and an open marsh.

There are numerous wild edible and medicinal plants in British Columbia that are used traditionally by First Nations peoples. These include seaweeds, rhizomes and shoots of flowering plants, berries, and fungi.

A staple food, food staple, or simply a staple, is a food that is eaten often and in such quantities that it constitutes a dominant portion of a standard diet for a given person or group of people, supplying a large fraction of energy needs and generally forming a significant proportion of the intake of other nutrients as well. A staple food of a specific society may be eaten as often as every day or every meal, and most people live on a diet based on just a small number of food staples. Specific staples vary from place to place, but typically are inexpensive or readily available foods that supply one or more of the macronutrients and micronutrients needed for survival and health: carbohydrates, proteins, fats, minerals, and vitamins. Typical examples include tubers and roots, grains, legumes, and seeds. Among them, cereals, legumes, tubers, and roots account for about 90% of the world's food calories intake.

Pediomelum argophyllum, synonym Psoralea argophylla, is a species of legume in the family Fabaceae. The species is native to the central United States, as well as the three Canadian prairie provinces, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Pediomelum argophyllum grows naturally as a forb, and it grows perennially.