The Mountain Meadows Massacre was a series of attacks during the Utah War that resulted in the mass murder of at least 120 members of the Baker–Fancher emigrant wagon train. The massacre occurred in the southern Utah Territory at Mountain Meadows, and was perpetrated by settlers from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints involved with the Utah Territorial Militia who recruited and were aided by some Southern Paiute Native Americans. The wagon train, made up mostly of families from Arkansas, was bound for California, traveling on the Old Spanish Trail that passed through the Territory.

In Mormonism, the endowment is a two-part ordinance (ceremony) designed for participants to become kings, queens, priests, and priestesses in the afterlife. As part of the first ceremony, participants take part in a scripted reenactment of the Biblical creation and fall of Adam and Eve. The ceremony includes a symbolic washing and anointing, and receipt of a "new name" which they are not to reveal to others except at a certain part in the ceremony, and the receipt of the temple garment, which Mormons then are expected to wear under their clothing day and night throughout their life. Participants are taught symbolic gestures and passwords considered necessary to pass by angels guarding the way to heaven, and are instructed not to reveal them to others. As practiced today in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the endowment also consists of a series of covenants that participants make, such as a covenant of consecration to the LDS Church. All LDS Church members who choose to serve as missionaries or participate in a celestial marriage in a temple must first complete the first endowment ceremony.

In the Latter Day Saint movement the second anointing is the pinnacle ordinance of the temple and an extension of the endowment ceremony. Founder Joseph Smith taught that the function of the ordinance was to ensure salvation, guarantee exaltation, and confer godhood. In the ordinance, a participant is anointed as a "priest and king" or a "priestess and queen", and is sealed to the highest degree of salvation available in Mormon theology.

Within Mormonism, the priesthood authority to act in God's name was said by its founder, Joseph Smith, to have been removed from the primitive Christian church through a Great Apostasy, which Mormons believe occurred due to the deaths of the original apostles. Mormons maintain that this apostasy was prophesied of within the Bible to occur prior to the Second Coming of Jesus and was therefore in keeping with God's plan for mankind. Smith claimed that the priesthood authority was restored to him from angelic beings—John the Baptist and the apostles Peter, James, and John.

During the history of the Latter Day Saint movement, the relationship between Black people and Mormonism has included enslavement, exclusion and inclusion, and official and unofficial discrimination. Black people have been involved with the Latter Day Saint movement since its inception in the 1830s. Their experiences have varied widely, depending on the denomination within Mormonism and the time of their involvement. From the mid-1800s to 1978, Mormonism's largest denomination – the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints – barred Black women and men from participating in the ordinances of its temples necessary for the highest level of salvation, prevented most men of Black African descent from being ordained into the church's lay, all-male priesthood, supported racial segregation in its communities and schools, taught that righteous Black people would be made white after death, and opposed interracial marriage. The temple and priesthood racial restrictions were lifted by church leaders in 1978. In 2013, the church disavowed its previous teachings on race for the first time.

The status of women in Mormonism has been a source of public debate since before the death of Joseph Smith in 1844. Various denominations within the Latter Day Saint movement have taken different paths on the subject of women and their role in the church and in society. Views range from the full equal status and ordination of women to the priesthood, as practiced by the Community of Christ, to a patriarchal system practiced by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, to the ultra-patriarchal plural marriage system practiced by the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and other Mormon fundamentalist groups.

Blood atonement was a doctrine in the history of Mormonism still adhered to by some fundamentalist splinter groups, under which the atonement of Jesus does not redeem an eternal sin. To atone for an eternal sin, the sinner should be killed in a way that allows his blood to be shed upon the ground as a sacrificial offering, so he does not become a son of perdition. The largest Mormon denomination, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, has denied the validity of the doctrine since 1889 with early church leaders referring to it as a "fiction" in spite of evidence to the contrary and later church leaders referring to it as a "theoretical principle" that had never been implemented in the LDS Church.

Sexuality has a prominent role within the theology of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In its standards for sexual behavior called the law of chastity, top LDS leaders bar all premarital sex, all homosexual sexual activity, the viewing of pornography, masturbation, and overtly sexual kissing, dancing, and touch outside marriage. LDS Leaders teach that gender is defined in premortal life, and that part of the purpose of mortal life is for men and women to be sealed together in heterosexual marriages, progress eternally after death as gods together, and produce spiritual children in the afterlife. The church states that sexual relations within the framework of monogamous opposite-sex marriage are healthy, necessary, and approved by God. The LDS denomination of Mormonism places great emphasis on the sexual behavior of Mormon adherents, as a commitment to follow the law of chastity is required for baptism, adherence is required to receive a temple recommend, and is part of the temple endowment ceremony covenants devout participants promise by oath to keep.

In Mormonism, the oath of vengeance was part of the endowment ritual of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Participants swore an oath to pray for God to avenge the blood of prophets Joseph Smith and Hyrum Smith, who were assassinated in 1844. The oath was part of the ceremony from about 1845 until the early 1930s.

Mormons have experienced significant instances of violence throughout their history as a religious group. In the early history of the United States, violence was used as a form of control. Mormons faced persecution and forceful expulsion from several locations. They were driven from Ohio to Missouri, and from Missouri to Illinois. Eventually, they settled in the Utah Territory. These migrations were often accompanied by acts of violence, including massacres, home burnings, and pillaging.

The Good Neighbor policy is the 1927 reform of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that removed any suggestion in church literature, sermons, and ordinances that its members should seek vengeance on US citizens or governments, particularly for the assassinations of its founder Joseph Smith and his brother, Hyrum.

Mormon theology has long been thought to be one of the causes of the Mountain Meadows Massacre. The victims of the massacre, known as the Baker–Fancher party, were passing through the Utah Territory to California in 1857. For the decade prior the emigrants' arrival, Utah Territory had existed as a theocracy led by Brigham Young. As part of Young's vision of a pre-millennial "Kingdom of God," Young established colonies along the California and Old Spanish Trails, where Mormon officials governed as leaders of church, state, and military. Two of the southernmost establishments were Parowan and Cedar City, led respectively by Stake Presidents William H. Dame and Isaac C. Haight. Haight and Dame were, in addition, the senior regional military leaders of the Mormon militia. During the period just before the massacre, known as the Mormon Reformation, Mormon teachings were dramatic and strident. The religion had undergone a period of intense persecution in the American mid-west.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has been subject to criticism and sometimes discrimination since its inception.

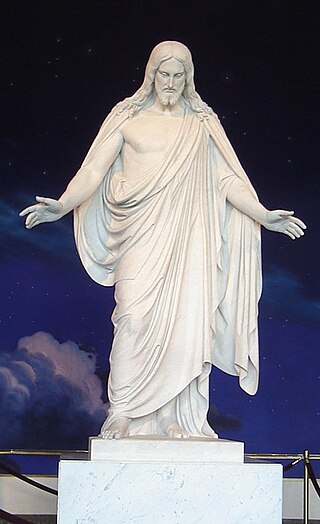

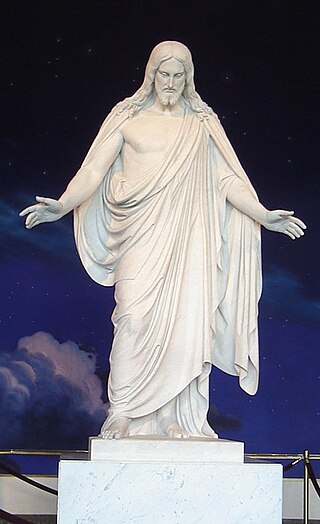

In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a temple is a building dedicated to be a House of the Lord. Temples are considered by church members to be the most sacred structures on earth.

In the theology of the Latter Day Saint movement, an endowment refers to a gift of "power from on high", typically associated with the ordinances performed in Latter Day Saint temples. The purpose and meaning of the endowment varied during the life of movement founder Joseph Smith. The term has referred to many such gifts of heavenly power, including the confirmation ritual, the institution of the High Priesthood in 1831, events and rituals occurring in the Kirtland Temple in the mid-1830s, and an elaborate ritual performed in the Nauvoo Temple in the 1840s.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and a topical guide to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

In the past, leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have consistently opposed marriages between members of different ethnicities, though interracial marriage is no longer considered a sin. In 1977, apostle Boyd K. Packer publicly stated that "[w]e've always counseled in the Church for our Mexican members to marry Mexicans, our Japanese members to marry Japanese, our Caucasians to marry Caucasians, our Polynesian members to marry Polynesians. ... The counsel has been wise." Nearly every decade for over a century—beginning with the church's formation in the 1830s until the 1970s—has seen some denunciations of interracial marriages (miscegenation), with most statements focusing on Black–White marriages. Church president Brigham Young taught on multiple occasions that Black–White marriage merited death for the couple and their children.

Thomas Coleman, a Black man formerly enslaved by Mormons, was murdered in 1866 in Salt Lake City, Utah. Sources report the lynching was a hate crime and was committed by a friend or family member of a White woman Coleman allegedly had been seen walking with before. The killer(s) slit his throat deeply and castrated his body. They then dumped his body near where the Utah State Capitol is now located, and pinned a note to his chest which said in large letters, "Notice to all niggers! Take warning!! Leave white women alone!!!"

In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints —Mormonism's largest denomination—there have been numerous changes to temple ceremonies over time in the church's over-200-year history. Temples are not churches or meetinghouses designated for public weekly worship services, but rather sacred places that only admit members in good standing with a recommendation from their leaders. LDS Church members perform rituals within temples. They are taught that God has deemed these ordinances as essential to achieving the faith's ultimate goal after death of exaltation. They are also taught that a vast number of dead spirits exist in a condition termed spirit prison for whom when the temple ordinances are completed will have the option to accept the ordinances and be freed of their imprisonment. These temple ordinances are performed by a living church member for themself and "on behalf of the dead" or "by proxy".