Celtic Christianity is a form of Christianity that was common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages. Some writers have described a distinct Celtic Church uniting the Celtic peoples and distinguishing them from adherents of the Roman Church, while others classify Celtic Christianity as a set of distinctive practices occurring in those areas. Varying scholars reject the former notion, but note that there were certain traditions and practices present in both the Irish and British churches that were not seen in the wider Christian world.

Penance is any act or a set of actions done out of repentance for sins committed, as well as an alternate name for the Catholic, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox sacrament of Reconciliation or Confession. It also plays a part in confession among Anglicans and Methodists, in which it is a rite, as well as among other Protestants.

Finnian of Movilla was an Irish Christian missionary. His feast day is 10 September.

Finnian of Clonard – also Finian, Fionán or Fionnán in Irish; or Finianus and Finanus in its Latinised form (470–549) – was one of the early Irish monastic saints, who founded Clonard Abbey in modern-day County Meath. The Twelve Apostles of Ireland studied under him. Finnian of Clonard is considered one of the fathers of Irish monasticism.

Saint Comgall, an early Irish saint, was the founder and abbot of the great Irish monastery at Bangor in Ireland.

A penitential is a book or set of church rules concerning the Christian sacrament of penance, a "new manner of reconciliation with God" that was first developed by Celtic monks in Ireland in the sixth century AD. It consisted of a list of sins and the appropriate penances prescribed for them, and served as a type of manual for confessors.

Ailerán, also known as Ailerán Sapiens was an Irish scholar and saint who died on 29 December 664 or 665. His feast day is 29 December.

The Catholic Church historically observes the disciplines of fasting and abstinence at various times each year. For Catholics, fasting is the reduction of one's intake of food, while abstinence refers to refraining from something that is good, and not inherently sinful, such as meat. The Catholic Church teaches that all people are obliged by God to perform some penance for their sins, and that these acts of penance are both personal and corporeal. Bodily fasting is meaningless unless it is joined with a spiritual avoidance of sin. Basil of Caesarea gives the following exhortation regarding fasting:

Let us fast an acceptable and very pleasing fast to the Lord. True fast is the estrangement from evil, temperance of tongue, abstinence from anger, separation from desires, slander, falsehood and perjury. Privation of these is true fasting.

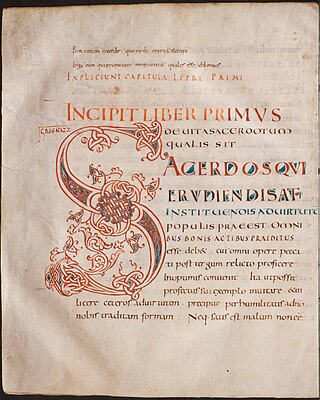

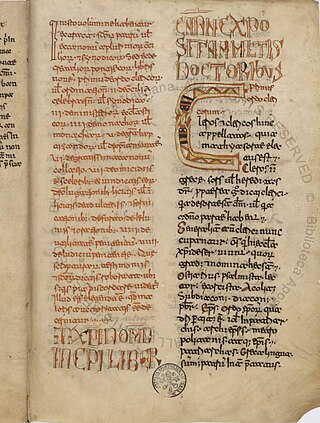

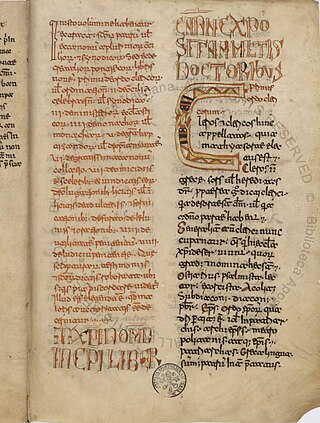

The Collectio canonum Hibernensis is a systematic Latin collection of Continental canon law, scriptural and patristic excerpts, and Irish synodal and penitential decrees. Hib is thought to have been compiled by two Irish scholars working in the late 7th or 8th century, Cú Chuimne of Iona and Ruben of Dairinis.

Clonard Abbey was an early medieval monastery situated on the River Boyne in Clonard, County Meath, Ireland.

Movilla Abbey in Newtownards, County Down, Northern Ireland, is believed to have been one of Ulster's and Ireland's most important monasteries. Movilla should not be confused with Moville in County Donegal.

Handbook for a Confessor is a compilation of Old English and Latin penitential texts associated with – and possibly authored or adapted by – Wulfstan (II), Archbishop of York. The handbook was intended for the use of parish priests in hearing confession and determining penances. Its transmission in the manuscripts seems to bear witness to Wulfstan's profound concern with these sacraments and their regulation, an impression which is similarly borne out by his Canons of Edgar, a guide of ecclesiastical law also targeted at priests. The handbook is a derivative work, based largely on earlier vernacular representatives of the penitential genre such as the Scrifboc and the Old English Penitential. Nevertheless, a unique quality seems to lie in the more or less systematic way it seeks to integrate various points of concern, including the proper formulae for confession and instructions on the administration of confession, the prescription of penances and their commutation.

The Vita Sancti Niniani or simply Vita Niniani is a Latin language Christian hagiography written in northern England in the mid-12th century. Using two earlier Anglo-Latin sources, it was written by Ailred of Rievaulx seemingly at the request of a Bishop of Galloway. It is loosely based on the career of the early British churchman Uinniau or Finnian, whose name through textual misreadings was rendered "Ninian" by high medieval English and Anglo-Norman writers, subsequently producing a distinct cult. Saint Ninian was thus an "unhistorical doppelganger" of someone else. The Vita tells "Ninian's" life-story, and relates ten miracles, six during the saint's lifetime and four posthumous.

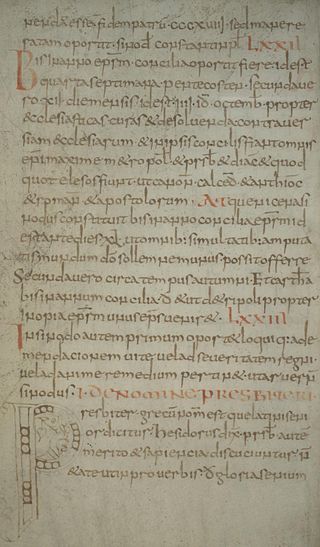

The Collectio canonum quadripartita is an early medieval canon law collection, written around the year 850 in the ecclesiastical province of Reims. It consists of four books. The Quadripartita is an episcopal manual of canon and penitential law. It was a popular source for knowledge of penitential and canon law in France, England and Italy in the ninth and tenth centuries, notably influencing Regino's enormously important Libri duo de synodalibus causis. Even well into the thirteenth century the Quadripartita was being copied by scribes and quoted by canonists who were compiling their own collections of canon law.

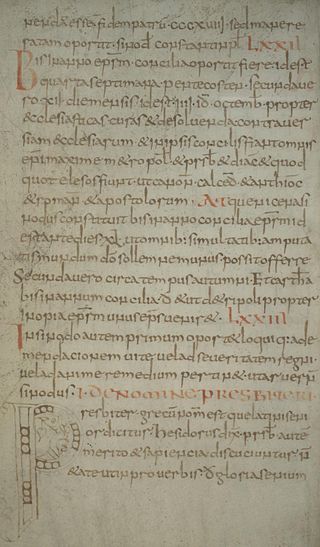

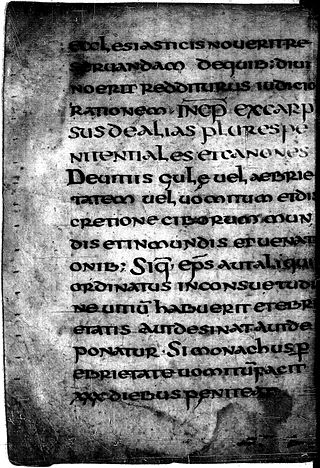

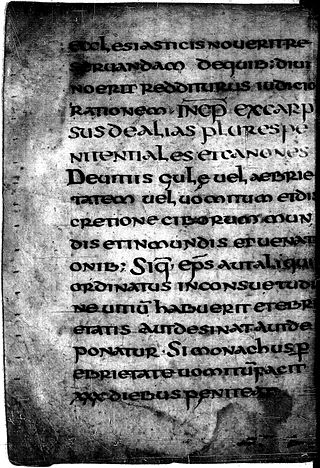

The Excarpsus Cummeani, also called the Pseudo-Cummeani, is an eighth-century penitential, probably written in the north of the Frankish Empire in Corbie Abbey. Twenty-six copies of the manuscript survive; six of those were copied before 800 CE. It is possible that the penitential, which extends its scope beyond monasticism to include clerics and lay people, has a connection to Saint Boniface and his efforts to reform the Frankish church in the first half of the eighth century. Geographic spread by the end of the eighth century and continued copying of the manuscript into the 9th and 10th centuries have been interpreted to mean the work was considered "by the Christian authorities" a canonical text. It was used as late as the eleventh century, "as the main source of the P. Parisiense compositum.

The Penitential of Cummean is an Irish penitential, presumably composed c. 650 by an Irish monk named Cummean. It served as a type of handbook for confessors.

The Bobbio Missal is a seventh-century Christian liturgical codex that probably originated in France.

The Paenitentiale Ecgberhti is an early medieval penitential handbook composed around 740, possibly by Archbishop Ecgberht of York.

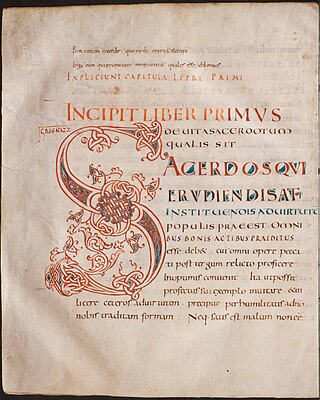

The Paenitentiale Theodori is an early medieval penitential handbook based on the judgements of Archbishop Theodore of Canterbury. It exists in multiple versions, the fullest and historically most important of which is the U or Discipulus Umbrensium version, composed (probably) in Northumbria within approximately a decade or two after Theodore's death. Other early though far less popular versions are those known today as the Capitula Dacheriana, the Canones Gregorii, the Canones Basilienses, and the Canones Cottoniani, all of which were compiled before the Paenitentiale Umbrense probably in either Ireland and/or England during or shortly after Theodore's lifetime.

The Ermenfrid Penitential is an ordinance composed by the Bishops of Normandy following the Battle of Hastings (1066) calling for atonement to be completed by the perpetrators of violence in William the Conqueror's invading army during the Norman Conquest of England. The date of issue is, probably, 1067. Some historians have dated it to 1070. Papal authority was given to the document by Ermenfrid of Sion, papal legate to Pope Alexander II (1063-1073).