The face is the front of an animal's head that features the eyes, nose and mouth, and through which animals express many of their emotions. The face is crucial for human identity, and damage such as scarring or developmental deformities may affect the psyche adversely.

Genetic testing, also known as DNA testing, is used to identify changes in DNA sequence or chromosome structure. Genetic testing can also include measuring the results of genetic changes, such as RNA analysis as an output of gene expression, or through biochemical analysis to measure specific protein output. In a medical setting, genetic testing can be used to diagnose or rule out suspected genetic disorders, predict risks for specific conditions, or gain information that can be used to customize medical treatments based on an individual's genetic makeup. Genetic testing can also be used to determine biological relatives, such as a child's biological parentage through DNA paternity testing, or be used to broadly predict an individual's ancestry. Genetic testing of plants and animals can be used for similar reasons as in humans, to gain information used for selective breeding, or for efforts to boost genetic diversity in endangered populations.

Archaeogenetics is the study of ancient DNA using various molecular genetic methods and DNA resources. This form of genetic analysis can be applied to human, animal, and plant specimens. Ancient DNA can be extracted from various fossilized specimens including bones, eggshells, and artificially preserved tissues in human and animal specimens. In plants, ancient DNA can be extracted from seeds and tissue. Archaeogenetics provides us with genetic evidence of ancient population group migrations, domestication events, and plant and animal evolution. The ancient DNA cross referenced with the DNA of relative modern genetic populations allows researchers to run comparison studies that provide a more complete analysis when ancient DNA is compromised.

Elmet, sometimes Elmed or Elmete, was an independent Brittonic Celtic Cumbric speaking kingdom between about the 4th century and mid 7th century.

The Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP) was started by Stanford University's Morrison Institute in 1990s along with collaboration of scientists around the world. It is the result of many years of work by Luigi Cavalli-Sforza, one of the most cited scientists in the world, who has published extensively in the use of genetics to understand human migration and evolution. The HGDP data sets have often been cited in papers on such topics as population genetics, anthropology, and heritable disease research.

Bryan Clifford Sykes was a British geneticist and science writer who was a Fellow of Wolfson College and Emeritus Professor of human genetics at the University of Oxford.

Sir Walter Fred Bodmer is a German-born British human geneticist.

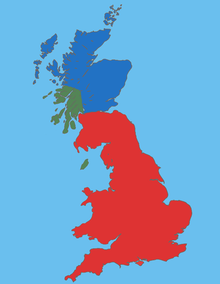

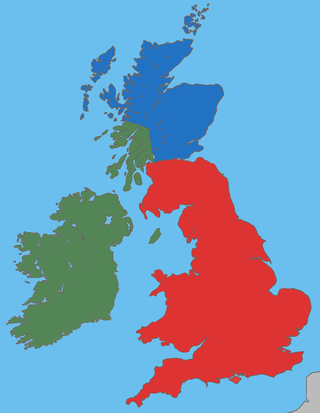

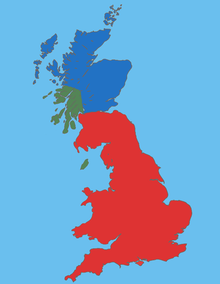

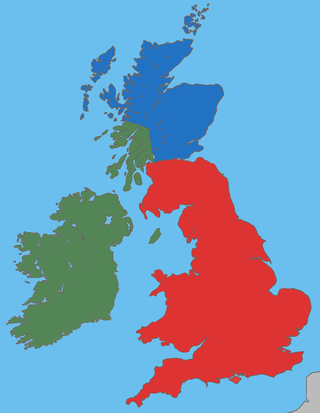

The Welsh are an ethnic group native to Wales. Wales is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. The majority of people living in Wales are British citizens.

The Britons, also known as Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons, were the indigenous Celtic people who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age until the High Middle Ages, at which point they diverged into the Welsh, Cornish, and Bretons. They spoke Common Brittonic, the ancestor of the modern Brittonic languages.

The historical immigration to Great Britain concerns the movement of people, cultural and ethnic groups to the British Isles before Irish independence in 1922. Immigration after Irish independence is dealt with by the article Immigration to the United Kingdom since Irish independence.

Haplogroup I-M253, also known as I1, is a Y chromosome haplogroup. The genetic markers confirmed as identifying I-M253 are the SNPs M253,M307.2/P203.2, M450/S109, P30, P40, L64, L75, L80, L81, L118, L121/S62, L123, L124/S64, L125/S65, L157.1, L186, and L187. It is a primary branch of Haplogroup I-M170 (I*).

The Karitiana or Caritiana are an indigenous people of Brazil, whose reservation is located in the western Amazon. They count 320 members, and the leader of their tribal association is Renato Caritiana. They subsist by farming, fishing and hunting, and have almost no contact with the outside world. Their tongue, the Karitiâna language, is an Arikém language of Brazil.

The genetic history of the British Isles is the subject of research within the larger field of human population genetics. It has developed in parallel with DNA testing technologies capable of identifying genetic similarities and differences between both modern and ancient populations. The conclusions of population genetics regarding the British Isles in turn draw upon and contribute to the larger field of understanding the history of the human occupation of the area, complementing work in linguistics, archaeology, history and genealogy.

Blood of the Vikings was a five-part 2001 BBC Television documentary series that traced the legacy of the Vikings in the British Isles through a genetics survey.

The English people are an ethnic group and nation native to England, who speak the English language, a West Germanic language, and share a common history and culture. The English identity began with the Anglo-Saxons, when they were known as the Angelcynn, meaning race or tribe of the Angles. Their ethnonym is derived from the Angles, one of the Germanic peoples who migrated to Britain around the 5th century AD.

The settlement of Great Britain by diverse Germanic peoples, who eventually developed a common cultural identity as Anglo-Saxons, changed the language and culture of most of what became England from Romano-British to Germanic. This process principally occurred from the mid-fifth to early seventh centuries, following the end of Roman rule in Britain around the year 410. The settlement was followed by the establishment of the Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the south and east of Britain, later followed by the rest of modern England, and the south-east of modern Scotland. The exact nature of this change is a topic of on-going research. Questions remain about the scale, timing and nature of the settlements, and also about what happened to the previous residents of what is now England.

The Insular Celts were speakers of the Insular Celtic languages in the British Isles and Brittany. The term is mostly used for the Celtic peoples of the isles up until the early Middle Ages, covering the British–Irish Iron Age, Roman Britain and Sub-Roman Britain. They included the Celtic Britons, the Picts, and the Gaels.

The Bulgarians are part of the Slavic ethnolinguistic group as a result of migrations of Slavic tribes to the region since the 6th century AD and the subsequent linguistic assimilation of other populations.

Haplogroup I-Z63, also known as I1a3 per the International Society of Genetic Genealogy ('ISOGG), is a Y chromosome haplogroup. It is correlated with a DYS456 value inferior to 15, but there are exceptions.

Human genetic clustering refers to patterns of relative genetic similarity among human individuals and populations, as well as the wide range of scientific and statistical methods used to study this aspect of human genetic variation.