Nuremberg is the largest city in Franconia, the second-largest city in the German state of Bavaria, and its 545,000 inhabitants make it the 14th-largest city in Germany.

A watch is a portable timepiece intended to be carried or worn by a person. It is designed to keep a consistent movement despite the motions caused by the person's activities. A wristwatch is designed to be worn around the wrist, attached by a watch strap or other type of bracelet, including metal bands, leather straps, or any other kind of bracelet. A pocket watch is designed for a person to carry in a pocket, often attached to a chain.

A watchmaker is an artisan who makes and repairs watches. Since a majority of watches are now factory-made, most modern watchmakers only repair watches. However, originally they were master craftsmen who built watches, including all their parts, by hand. Modern watchmakers, when required to repair older watches, for which replacement parts may not be available, must have fabrication skills, and can typically manufacture replacements for many of the parts found in a watch. The term clockmaker refers to an equivalent occupation specializing in clocks.

A clockmaker is an artisan who makes and/or repairs clocks. Since almost all clocks are now factory-made, most modern clockmakers only repair clocks. Modern clockmakers may be employed by jewellers, antique shops, and places devoted strictly to repairing clocks and watches. Clockmakers must be able to read blueprints and instructions for numerous types of clocks and time pieces that vary from antique clocks to modern time pieces in order to fix and make clocks or watches. The trade requires fine motor coordination as clockmakers must frequently work on devices with small gears and fine machinery.

An escapement is a mechanical linkage in mechanical watches and clocks that gives impulses to the timekeeping element and periodically releases the gear train to move forward, advancing the clock's hands. The impulse action transfers energy to the clock's timekeeping element to replace the energy lost to friction during its cycle and keep the timekeeper oscillating. The escapement is driven by force from a coiled spring or a suspended weight, transmitted through the timepiece's gear train. Each swing of the pendulum or balance wheel releases a tooth of the escapement's escape wheel, allowing the clock's gear train to advance or "escape" by a fixed amount. This regular periodic advancement moves the clock's hands forward at a steady rate. At the same time, the tooth gives the timekeeping element a push, before another tooth catches on the escapement's pallet, returning the escapement to its "locked" state. The sudden stopping of the escapement's tooth is what generates the characteristic "ticking" sound heard in operating mechanical clocks and watches.

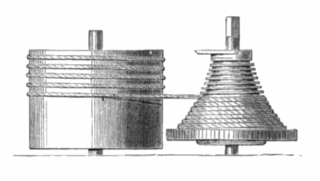

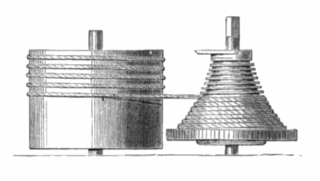

A mainspring is a spiral torsion spring of metal ribbon—commonly spring steel—used as a power source in mechanical watches, some clocks, and other clockwork mechanisms. Winding the timepiece, by turning a knob or key, stores energy in the mainspring by twisting the spiral tighter. The force of the mainspring then turns the clock's wheels as it unwinds, until the next winding is needed. The adjectives wind-up and spring-powered refer to mechanisms powered by mainsprings, which also include kitchen timers, metronomes, music boxes, wind-up toys and clockwork radios.

The vergeescapement is the earliest known type of mechanical escapement, the mechanism in a mechanical clock that controls its rate by allowing the gear train to advance at regular intervals or 'ticks'. Verge escapements were used from the late 13th century until the mid 19th century in clocks and pocketwatches. The name verge comes from the Latin virga, meaning stick or rod.

A fusee is a cone-shaped pulley with a helical groove around it, wound with a cord or chain attached to the mainspring barrel of antique mechanical watches and clocks. It was used from the 15th century to the early 20th century to improve timekeeping by equalizing the uneven pull of the mainspring as it ran down. Gawaine Baillie stated of the fusee, "Perhaps no problem in mechanics has ever been solved so simply and so perfectly."

The history of watches began in 16th-century Europe, where watches evolved from portable spring-driven clocks, which first appeared in the 15th century.

Louis George was a Prussian master watchmaker of the late baroque era.

Nuremberg Funnel is a jocular description of a mechanical way of learning and teaching. On the one hand, it evokes the image of a student learning his lessons with this kind of teaching method almost without effort and on the other hand, a teacher teaching everything to even the "stupidest" pupil. It can also reference forceful teaching of someone's ideas, ideology, etc.

A Nuremberg egg is a type of small ornamental spring-driven clock made to be worn around the neck, produced in Nuremberg in the mid-to-late 16th century.

Heinlein or Henlein is a German surname. Notable people with the surname include:

The Free Imperial City of Nuremberg was a free imperial city – independent city-state – within the Holy Roman Empire. After Nuremberg gained piecemeal independence from the Burgraviate of Nuremberg in the High Middle Ages and considerable territory from Bavaria in the Landshut War of Succession, it grew to become one of the largest and most important Imperial cities, the 'unofficial capital' of the Empire, particularly because numerous Imperial Diets and courts met at Nuremberg Castle between 1211 and 1543. Because of the many Diets of Nuremberg, Nuremberg became an important routine place of the administration of the Empire during this time. The Golden Bull of 1356, issued by Emperor Charles IV, named Nuremberg as the city where newly elected kings of Germany must hold their first Imperial Diet, making Nuremberg one of the three highest cities of the Empire.

A stackfreed is a simple spring-loaded cam mechanism used in some of the earliest antique spring-driven clocks and watches to even out the force of the mainspring, to improve timekeeping accuracy. Stackfreeds were used in some German clocks and watches from the 16th to the 17th century, before they were replaced in later timepieces by the fusee. The term may have come from a compound of the German words starke ("strong") and feder ("spring").

Stephan Farffler, sometimes spelled Stephan Farfler, was a German watchmaker of the seventeenth century whose invention of a manumotive carriage in 1655 is widely considered to have been the first self-propelled wheelchair. The three-wheeled device is also believed to have been a precursor to the modern-day tricycle and bicycle.

The following is a timeline of the history of the city of Nuremberg, Germany.

The Watch 1505 is the world's first watch. It was crafted by the German inventor, locksmith and watchmaker Peter Henlein from Nuremberg, during the year 1505, in the early German Renaissance period, as part of the Northern Renaissance. However, other German clockmakers were creating miniature timepieces during this period, and there is no definite evidence Henlein was the first. It is the oldest watch in the world that still works. The watch is a small fire-gilded copper sphere, an oriental pomander, and combines German engineering with Oriental influences. In 1987, the watch reappeared at an antiques and flea market in London. The initial price estimation for this watch is between 50 and 80 million dollars.

Hans Hautsch was a toolmaker and inventor from Ledergasse, Nuremberg. His father, Antoni (1563–1627), and grandfather, Kilian, were both toolmakers.