The Last Supper is a mural painting by the Italian High Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci, dated to c. 1495–1498, housed in the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy. The painting represents the scene of the Last Supper of Jesus with the Twelve Apostles, as it is told in the Gospel of John – specifically the moment after Jesus announces that one of his apostles will betray him. Its handling of space, mastery of perspective, treatment of motion and complex display of human emotion has made it one of the Western world's most recognizable paintings and among Leonardo's most celebrated works. Some commentators consider it pivotal in inaugurating the transition into what is now termed the High Renaissance.

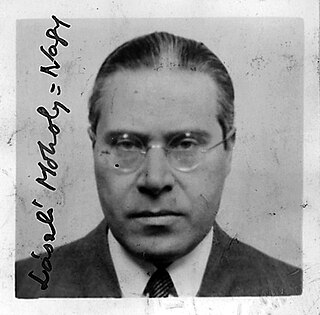

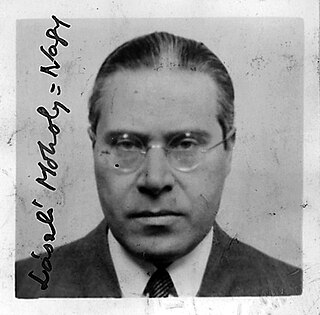

László Moholy-Nagy was a Hungarian painter and photographer as well as a professor in the Bauhaus school. He was highly influenced by constructivism and a strong advocate of the integration of technology and industry into the arts. The art critic Peter Schjeldahl called him "relentlessly experimental" because of his pioneering work in painting, drawing, photography, collage, sculpture, film, theater, and writing.

Bridget Louise Riley is an English painter known for her op art paintings. She lives and works in London, Cornwall and the Vaucluse in France.

Op art, short for optical art, is a style of visual art that uses optical illusions.

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge was an English singer-songwriter, musician, poet, performance artist, visual artist, and occultist who rose to notoriety as the founder of the COUM Transmissions artistic collective and lead vocalist of seminal industrial band Throbbing Gristle. They were also a founding member of Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth occult group, and fronted the experimental pop rock band Psychic TV.

Psychic TV were an English experimental video art and music group, formed by performance artist Genesis P-Orridge and Scottish musician Alex Fergusson in 1981 after the break-up of Throbbing Gristle.

COUM Transmissions was a music and performance art collective who operated in the United Kingdom from 1969 through to 1976. The collective was influenced by the Dada and surrealism artistic movements, the writers of the Beat Generation, and underground music. COUM were openly confrontational and subversive, challenging aspects of conventional British society. Founded in Hull, Yorkshire, by Genesis P-Orridge, other prominent early members included Cosey Fanni Tutti and Spydeee Gasmantell. Part-time members included Tim Poston, Brook Menzies, Haydn Robb, Les Maull, Ray Harvey, John (Jonji) Smith, Foxtrot Echo, Fizzy Paet, and John Gunni Busck. Later members included Peter "Sleazy" Christopherson and Chris Carter, who together with P-Orridge and Tutti went on to found the pioneering industrial band Throbbing Gristle in 1976.

Otto Piene was a German-American artist specializing in kinetic and technology-based art, often working collaboratively. He lived and worked in Düsseldorf, Germany; Cambridge, Massachusetts; and Groton, Massachusetts.

Richard Allen was a British Minimalist, Abstract, Systems, Fundamental, and Geometric painter and printmaker. Allen worked prolifically from 1960 until his death, in 1999, from motor neurone disease.

Erich Buchholz (1891–1972) was a German artist in painting and printmaking. He was a central figure in the development of non-objective or concrete art in Berlin between 1918 and 1924. He interrupted his artistic activity in 1925, first because of economic hardship and, from 1933, as he was forbidden to paint by the National-Socialist authorities. He resumed artistic activity in 1945.

Lumino Kinetic art is a subset and an art historical term in the context of the more established kinetic art, which in turn is a subset of new media art. The historian of art Frank Popper views the evolution of this type of art as evidence of "aesthetic preoccupations linked with technological advancement" and a starting-point in the context of high-technology art. László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946), a member of the Bauhaus, and influenced by constructivism can be regarded as one of the fathers of Lumino kinetic art. Light sculpture and moving sculpture are the components of his Light-Space Modulator (1922–30), One of the first Light art pieces which also combines kinetic art.

Rainer Fetting is a German painter and sculptor.

Ian McKeever is a contemporary British artist. Since 1990 McKeever has lived and worked in Hartgrove, Dorset, England.

Winston Branch is a British artist originally from Saint Lucia, the sovereign island in the Caribbean Sea. He still has a home there, while maintaining a studio in California. Works by Branch are included in the collections of Tate Britain, the Legion of Honor De Young Museum in San Francisco, California, and the St Louis Museum of Art in Missouri. Branch was the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1978, the British Prix de Rome, a DAAD Fellowship to Berlin, a sponsorship to Belize from the Organization of American States, and was Artist in Residence at Fisk University in Tennessee. He has been a professor of fine arts and has taught at several art institutions in London and in the US. He has also worked as a theatrical set designer with various theatre groups.

Dieter Jung is a German artist working in the field of holography, painting and installation art. He lives and works in Berlin.

Space Studios, founded by Bridget Riley and Peter Sedgley in 1968, is the oldest continuously operating artists' studio organisation in London. In addition to providing studios to artists across the city, Space operates a recognised exhibition programme, international residencies and a community-facing learning and participation platform.

The British pavilion houses Great Britain's national representation during the Venice Biennale arts festivals.

Volker Diehl is a German gallery owner. He mainly exhibits contemporary art in the gallery "DIEHL" (Berlin).

Ann Finlayson was an English painter, draughtsperson and teacher. She worked as an assistant to Bridget Riley and Peter Sedgley from 1969 to 1971. She was best known for her abstract watercolours.

Norman Dilworth (1931-2023) was an English artist, born in Wigan, Lancashire. His work is systematic, constructivist and concrete. It is mainly exhibited and appreciated in continental Europe, where it is held in many national collections.