Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early November 1917 (N.S.)

The October Revolution, known in Soviet historiography as the Great October Socialist Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment in the larger Russian Revolution of 1917–1923. It was the second revolutionary change of government in Russia in 1917. It took place through an armed insurrection in Petrograd on 7 November 1917 [O.S. 25 October]. It was the precipitating event of the Russian Civil War.

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social change in the Russian Empire, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government following two successive revolutions and a bloody civil war. The Russian Revolution can also be seen as the precursor for the other European revolutions that occurred during or in the aftermath of World War I, such as the German Revolution of 1918–1919.

The Kornilov affair, or the Kornilov putsch, was an attempted military coup d'état by the commander-in-chief of the Russian Army, General Lavr Kornilov, from 10 to 13 September 1917, against the Russian Provisional Government headed by Aleksander Kerensky and the Petrograd Soviet of Soldiers' and Workers' Deputies. The exact details and motivations of the Kornilov affair are unconfirmed due to the general confusion of all parties involved. Many historians have had to piece together varied historical accounts as a result.

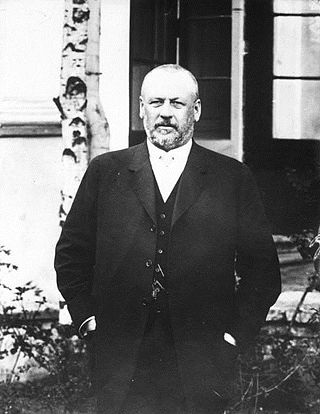

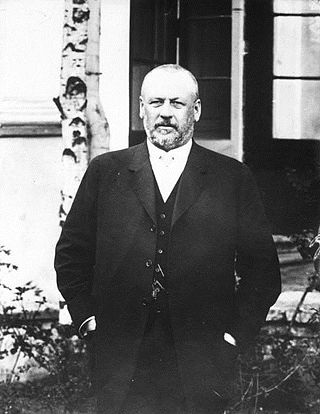

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the Constitutional Democratic party. He changed his view on the monarchy between 1905 and 1917. In the Russian Provisional Government, he served as Foreign Minister, working to prevent Russia's exit from the First World War.

"Dual power" refers to the coexistence of two governments as a result of the February Revolution: the Soviets, particularly the Petrograd Soviet, and the Russian Provisional Government. The term was first used by the communist Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924) in the Pravda article titled "The Dual Power".

The history of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was generally perceived as covering that of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party from which it evolved. The date 1912 is often identified as the time of the formation of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as a distinct party, and its history since then can roughly be divided into the following periods:

Mikhail Vladimirovich Rodzianko was a Russian statesman of Ukrainian origin. Known for his colorful language and conservative politics, he was the State Councillor and chamberlain of the Imperial family, Chairman of the State Duma and one of the leaders of the February Revolution of 1917, during which he headed the Provisional Committee of the State Duma. He was a key figure in the events that led to the abdication of Nicholas II of Russia on 15 March 1917.

Matvey Ivanovich Skobelev was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and politician.

The Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, commonly known as the Petrograd Soviet Ispolkom was a self-appointed executive committee of the Petrograd Soviet. As an antagonist of the Russian Provisional Government, after the 1917 February Revolution in Russia, the Ispolkom became a second center of power. It was dissolved during the Bolshevik October Revolution later that year.

The July Days were a period of unrest in Petrograd, Russia, between 16–20 July [O.S. 3–7 July] 1917. It was characterised by spontaneous armed demonstrations by soldiers, sailors, and industrial workers engaged against the Russian Provisional Government. The demonstrations were angrier and more violent than those during the February Revolution months earlier.

The Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee was a militant group of the Petrograd Soviet and one of several military revolutionary committees that were created in the Russian Republic. Initially the committee was created on 25 October 1917 after the German army secured the city of Riga and the West Estonian Archipelago. The committee's resolution was adopted by the Petrograd Soviet on October 29, 1917.

The Russian Provisional Government was a provisional government of the Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately after the abdication of Nicholas II. The intention of the provisional government was the organization of elections to the Russian Constituent Assembly and its convention. The provisional government, led first by Prince Georgy Lvov and then by Alexander Kerensky, lasted approximately eight months, and ceased to exist when the Bolsheviks gained power in the October Revolution in October [November, N.S.] 1917.

The Russian Baltic Fleet played an important role during the October Revolution and Russian Civil War. During the October Revolution the sailors of the Baltic Fleet were among the most ardent supporters of Bolsheviks, and formed an elite among Red military forces. Some ships of the fleet took part in the Russian Civil War, notably by clashing with the British navy operating in the Baltic as part of intervention forces. Over the years, however, the relations of the Baltic Fleet sailors with the Bolshevik regime soured, and they eventually rebelled against the Soviet government in the Kronstadt rebellion in 1921, but were defeated, and the Fleet de facto ceased to exist as an active military unit.

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies was a city council of Petrograd, the capital of Russia at the time. For brevity, it is usually called the Petrograd Soviet.

The February Revolution, known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution, was the first of two revolutions which took place in Russia in 1917.

In 1917, the Russian Army formally ceased to be the Imperial Russian Army when the power in Russia was transferred from the Empire to the Provisional Government.

Events from the year 1917 in Russia.

The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies was held on November 7–9, 1917, in Smolny, Petrograd. It was convened under the pressure of the Bolsheviks on the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the First Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies.

The Bolshevization of the Soviets was the process of winning a majority in the Soviets by the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (Bolsheviks) in the second half of 1917. The process was particularly active after the Kornilov Rebellion during September – October 1917 and was accompanied by the ousting from these bodies of power previously moderate socialists, primarily the Socialist Revolutionaries and Mensheviks, who dominated them.