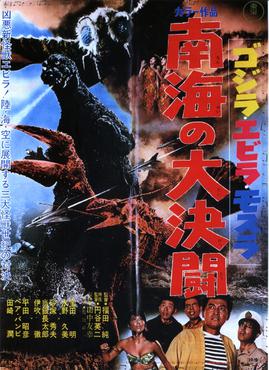

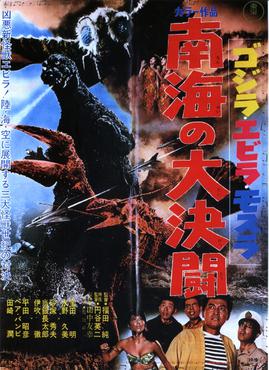

Ebirah, Horror of the Deep is a 1966 Japanese kaiju film directed by Jun Fukuda and produced and distributed by Toho Co., Ltd. The film stars Akira Takarada, Kumi Mizuno, Akihiko Hirata and Eisei Amamoto, and features the fictional monster characters Godzilla, Mothra, and Ebirah. It is the seventh film in the Godzilla franchise, and features special effects by Sadamasa Arikawa, under the supervision of Eiji Tsuburaya. In the film, Godzilla and Ebirah are portrayed by Haruo Nakajima and Hiroshi Sekita, respectively.

The Abyss is a 1989 American science fiction film written and directed by James Cameron and starring Ed Harris, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, and Michael Biehn. When an American submarine sinks in the Caribbean, a US search and recovery team works with an oil platform crew, racing against Soviet vessels to recover the boat. Deep in the ocean, they encounter something unexpected.

A title sequence is the method by which films or television programmes present their title and key production and cast members, utilizing conceptual visuals and sound. It typically includes the text of the opening credits, and helps establish the setting and tone of the program. It may consist of live action, animation, music, still images, and/or graphics. In some films, the title sequence is preceded by a cold open.

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla is a 1974 Japanese action-adventure kaiju film directed by Jun Fukuda, with special effects by Teruyoshi Nakano. Distributed by Toho and produced under their effects subsidiary Toho–Eizo, it is the 14th film of the Godzilla franchise, and features the fictional monster characters Godzilla, Anguirus, and King Caesar, along with the mecha character Mechagodzilla. The film stars Masaaki Daimon, Kazuya Aoyama, Gorō Mutsumi, and Akihiko Hirata, with Isao Zushi as Godzilla, Satoru Kuzumi as both Anguirus and King Caesar, and Kazunari Mori as Mechagodzilla. The film marks the first appearances of King Caesar and Mechagodzilla in the franchise.

Rankin/Bass Animated Entertainment was an American production company located in New York City, and known for its seasonal television specials, usually done in stop motion animation. Rankin/Bass's stop-motion productions are recognizable by their visual style of doll-like characters with spheroid body parts and ubiquitous powdery snow using an animation technique called Animagic.

House on Haunted Hill is a 1959 American horror film produced and directed by William Castle, written by Robb White and starring Vincent Price, Carol Ohmart, Richard Long, Alan Marshal, Carolyn Craig and Elisha Cook Jr. Price plays an eccentric millionaire, Frederick Loren, who, along with his wife Annabelle, has invited five people to the house for a "haunted house" party. Whoever stays in the house for one night will earn $10,000. As the night progresses, the guests are trapped within the house with an assortment of terrors. This film is perhaps best known for its promotional gimmick Emergo.

Barry Nathaniel Malzberg is an American writer and editor, most often of science fiction and fantasy.

Saul Bass was an American graphic designer and Oscar-winning filmmaker, best known for his design of motion-picture title sequences, film posters, and corporate logos.

Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie is a 1996 American science fiction comedy film and a film adaptation of the television series Mystery Science Theater 3000, produced and set between the series' sixth and seventh seasons. It was distributed by Universal Pictures and Gramercy Pictures and produced by Best Brains.

Extra Terrestrial Visitors is a 1983 science fiction film directed by Juan Piquer Simón. The film's original draft was meant to be a straightforward horror film about an evil alien on a murderous rampage, but the producers demanded script alterations in order to cash in on the success of Steven Spielberg's E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial by featuring a child and a cute, lovable alien.

Gamera, the Giant Monster is a 1965 Japanese kaiju film directed by Noriaki Yuasa, with special effects by Yonesaburo Tsukiji. Produced and distributed by Daiei Film, it is the first film in the Gamera franchise and the Shōwa era. The film stars Eiji Funakoshi, Harumi Kiritachi, and Junichiro Yamashita. In the film, authorities deal with the attacks of Gamera, a giant prehistoric turtle unleashed in the Arctic by an atomic bomb.

Neon Genesis Evangelion: Death & Rebirth, also romanized in Japan as Evangelion: Death and Evangelion: Rebirth, is a 1997 Japanese adult animated science fiction psychological drama film. It is the first installment of the Neon Genesis Evangelion feature film project and consists of two parts. The project, whose overarching title translates literally to New Era Evangelion: The Movie, was released in response to the success of the TV series and a strong demand by fans for an alternate ending. Its components have since been re-edited and re-released several times.

Futureworld is a 1976 American science fiction thriller film directed by Richard T. Heffron and written by Mayo Simon and George Schenck. It is a sequel to the 1973 Michael Crichton film Westworld, and is the second installment in the Westworld franchise. The film stars Peter Fonda, Blythe Danner, Arthur Hill, Stuart Margolin, John Ryan, and Yul Brynner, who makes an appearance in a dream sequence; no other cast member from the original film appears. Westworld's writer-director, Michael Crichton, and the original studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer were not involved in this production. Composer Fred Karlin was retained.

The Green Slime is a 1968 tokusatsu science fiction film directed by Kinji Fukasaku and produced by Walter Manley and Ivan Reiner. It was written by William Finger, Tom Rowe and Charles Sinclair from a story by Reiner. The film was shot in Japan with a Japanese director and film crew, but with the non-Japanese starring cast of Robert Horton, Richard Jaeckel and Luciana Paluzzi.

Gamera vs. Gyaos is a 1967 Japanese kaiju film directed by Noriaki Yuasa, with special effects by Yuasa. Produced by Daiei Film, it is the third entry in the Gamera franchise and stars Kojiro Hongo, Kichijiro Ueda, Tatsuemon Kanamura, Reiko Kasahara, and Naoyuki Abe, with Teruo Aragaki as Gamera. In the film, Gamera and authorities must deal with the sudden appearance of a carnivorous winged creature awakened by volcanic eruptions.

The Hellstrom Chronicle is an American film released in 1971 which combines elements of documentary, horror and apocalyptic prophecy to present a gripping satirical depiction of the struggle for survival between humans and insects. It won both the 1972 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature and BAFTA Award for Best Documentary. It was conceived and produced by David L. Wolper, directed by Walon Green and written by David Seltzer, who earned a Writers Guild of America Award nomination for his screenplay.

Robot Jox is a 1990 American post-apocalyptic Mecha science-fiction film directed by Stuart Gordon and starring Gary Graham, Anne-Marie Johnson and Paul Koslo. Co-written by science-fiction author Joe Haldeman, the film's plot follows Achilles, one of the "robot jox" who pilot giant machines that fight international battles to settle territorial disputes in a dystopian, post-apocalyptic world.

In science fiction and fantasy literatures, the term insectoid ("insect-like") denotes any fantastical fictional creature sharing physical or other traits with ordinary insects. Most frequently, insect-like or spider-like extraterrestrial life forms is meant; in such cases convergent evolution may presumably be responsible for the existence of such creatures. Occasionally, an earth-bound setting — such as in the film The Fly (1958), in which a scientist is accidentally transformed into a grotesque human–fly hybrid, or Kafka's famous novella The Metamorphosis (1915), which does not bother to explain how a man becomes an enormous insect — is the venue.

Phase 4, Phase IV or Phase Four may refer to:

List of the published work of Barry N. Malzberg, American writer.