Bosanska Krajina is a geographical region, a subregion of Bosnia, in western Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is enclosed by a number of rivers, namely the Sava (north), Glina (northwest), Vrbanja and Vrbas. The region is also a historic, economic and cultural entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina, noted for its preserved nature and wildlife diversity.

The Vrbas Banovina or Vrbas Banate, was a province (banovina) of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia between 1929 and 1941. It was named after the Vrbas River and consisted mostly of territory in western Bosnia with its capital at Banja Luka. Dvor district of present-day Croatia was also part of the Vrbas Banovina.

Gradiška, formerly Bosanska Gradiška, is a city of northwestern Bosnia and Herzegovina, located in Republika Srpska entity. As of 2013, it has a population of 51,727 inhabitants, while the city of Gradiška has a population of 14,368 inhabitants.

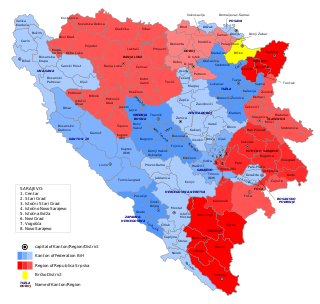

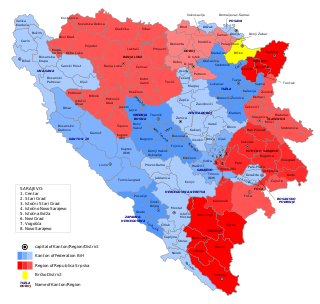

The Serbian Autonomous Oblast of Bosanska Krajina was a self-proclaimed Serbian Autonomous Oblast within today's Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was sometimes called the Autonomous Oblast of Krajina, or the Autonomous Region of Krajina (ARK). SAO Bosanska Krajina was located in the geographical region named Bosanska Krajina. Its capital was Banja Luka. The region was subsequently included into Republika Srpska.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the smallest administrative unit is the municipality. Prior to the 1992–95 Bosnian War there were 109 municipalities in what was then Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Ten of these formed the area of the capital Sarajevo.

Prnjavor is a town and municipality of Bosnia and Herzegovina, located in the Republika Srpska entity between cities of Banja Luka and Doboj. According to the 2013 census, the town has a population of 8,120 inhabitants, with 35,956 inhabitants in the municipality.

The Battle of Lijevče Field was a battle fought between 30 March and 8 April 1945 between the Croatian Armed Forces and Chetnik forces on the Lijevče field near Banja Luka in what was then the Independent State of Croatia (NDH).

The State Anti-fascist Council for the National Liberation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, commonly abbreviated as the ZAVNOBiH, was convened on 25 November 1943 in Mrkonjić Grad during the World War II Axis occupation of Yugoslavia. It was established as the highest representative and legislative body in the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina under control of the Yugoslav Partisans.

Đurađ "Đuro" Pucar "Stari" was a Yugoslav and Bosnian Serb politician.

Osman Karabegović was a Yugoslav and Bosnian communist politician and a recipient of the Order of the People's Hero. He joined the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in 1932.

Macedonians in Bosnia and Herzegovina refers to the group of ethnic Macedonians who reside in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Archives of Republika Srpska is an administrative organisation within the Ministry of Education and Culture of Republika Srpska, one of two constituent entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Archives' headquarters is in Banja Luka, and it has its regional offices in Doboj, Zvornik, Foča, Sokolac, and Trebinje. Its aim is to collect, store, preserve, organise, research, and provide access to archival materials on the territory of Republika Srpska, where it is designated as a central institution for the protection of cultural heritage. The Archives is also involved in research projects, exhibitions, and in the publishing of books and scholarly papers, mostly in the fields of archival science, history, and law. It is organised into two sectors, which are responsible for the protection of archival materials within and outside the Archives, respectively. The Archives currently holds 794 fonds and 35 collections, which span the period from the 17th century to the modern day.

Baljvine is a village located in the municipality of Mrkonjić Grad in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is in the administrative entity Republika Srpska. According to census estimates in 1991, the village population was 1,140. The population decreased from 973 to 437 people in 2013.

Vahida Maglajlić was a Yugoslav Partisan recognized as a People's Hero of Yugoslavia for her part in the struggle against the Axis powers during World War II. She was the only Bosnian Muslim woman to receive the order.

Vojislav "Đedo" Kecmanović was a Serb doctor who participated in the Balkan Wars and the National Liberation Struggle. He was the first President of the Presidium of the People's Assembly of PR Bosnia and Herzegovina and was also president of ZAVNOBiH.

The Women's Antifascist Front of Bosnia and Herzegovina, usually abbreviated to AFŽ BiH, was a mass organization in the People's Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was established by the Communist Party in February 1942, over a year before the republic itself, with the aim of mobilizing women in Bosnia and Herzegovina into the Partisan resistance against the Nazi occupation of Yugoslavia. It was one of the organizations which gave rise to the Women's Antifascist Front of Yugoslavia, the first congress of which was held in December 1942 in Bosanski Petrovac.

Rada Vranješević was a Yugoslav political activist and resistance leader in Bosnia during the Second World War.