Democide refers to "the intentional killing of an unarmed or disarmed person by government agents acting in their authoritative capacity and pursuant to government policy or high command." The term was first coined by Holocaust historian and statistics expert, R.J. Rummel in his book Death by Government, but has also been described as a better term than genocide to refer to certain types of mass killings, by renowned Holocaust historian Yehuda Bauer. According to Rummel, this definition covers a wide range of deaths, including forced labor and concentration camp victims, extrajudicial summary killings, and mass deaths due to governmental acts of criminal omission and neglect, such as in deliberate famines like the Holodomor, as well as killings by de facto governments, for example, killings during a civil war. This definition covers any murder of any number of persons by any government.

In political science, a revolution is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements at their core: (a) efforts to change the political regime that draw on a competing vision of a just order, (b) a notable degree of informal or formal mass mobilization, and (c) efforts to force change through noninstitutionalized actions such as mass demonstrations, protests, strikes, or violence."

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it also includes indirect methods aimed at forced migration by coercing the victim group to flee and preventing its return, such as murder, rape, and property destruction. Both the definition and charge of ethnic cleansing is often disputed, with some researchers including and others excluding coercive assimilation or mass killings as a means of depopulating an area of a particular group.

Mass killing is a concept which has been proposed by genocide scholars who wish to define incidents of non-combat killing which are perpetrated by a government or a state. A mass killing is commonly defined as the killing of group members without the intention to eliminate the whole group, or otherwise the killing of large numbers of people without a clear group membership.

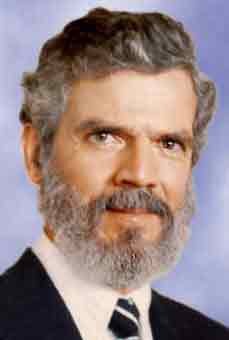

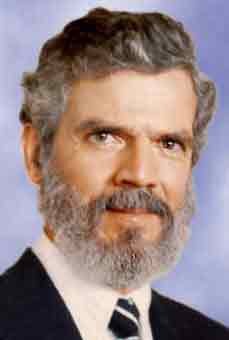

Rudolph Joseph Rummel was an American political scientist, a statistician and professor at Indiana University, Yale University, and University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. He spent his career studying data on collective violence and war with a view toward helping their resolution or elimination. Contrasting genocide, Rummel coined the term democide for murder by government, such as the genocide of indigenous peoples and colonialism, Nazi Germany, the Stalinist purges, Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution, and other authoritarian, totalitarian, or undemocratic regimes, coming to the conclusion that democratic regimes result in the least democides.

Rebellion is a violent uprising against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a portion of a state. A rebellion is often caused by political, religious, or social grievances that originate from a perceived inequality or marginalization. Rebellion comes from Latin re and bellum, and in Lockian philosophy refers to the responsibility of the people to overthrow unjust government.

The Polity data series is a data series in political science research. Along with the V-Dem Democracy indices project and Democracy Index, Polity is among prominent datasets that measure democracy and autocracy.

Ted Robert Gurr was an American author and professor of political science who most notably wrote about political conflict and instability. His widely translated book Why Men Rebel (1970) emphasized the importance of social psychological factors and ideology as root sources of political violence. He was Distinguished University Professor emeritus at the University of Maryland and consulted on projects he established there. He died in November 2017.

Political cleansing of a population is the elimination of categories of people in specific areas for political reasons. The means may vary and include forced migration, ethnic cleansing and population transfers.

Mass killings under communist regimes occurred through a variety of means during the 20th century, including executions, famine, deaths through forced labour, deportation, starvation, and imprisonment. Some of these events have been classified as genocides or crimes against humanity. Other terms have been used to describe these events, including classicide, democide, red holocaust, and politicide. The mass killings have been studied by authors and academics and several of them have postulated the potential causes of these killings along with the factors which were associated with them. Some authors have tabulated a total death toll, consisting of all of the excess deaths which cumulatively occurred under the rule of communist states, but these death toll estimates have been criticised. Most frequently, the states and events which are studied and included in death toll estimates are the Holodomor and the Great Purge in the Soviet Union, the Great Chinese Famine and the Cultural Revolution in the People's Republic of China, and the Cambodian genocide in Democratic Kampuchea. Estimates of individuals killed range from a low of 10–20 million to as high as 148 million.

Barbara Harff is professor of political science emerita at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. In 2003 and again in 2005 she was a distinguished visiting professor at the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Clark University. Her research focuses on the causes, risks, and prevention of genocidal violence.

Political violence is violence which is perpetrated in order to achieve political goals. It can include violence which is used by a state against other states (war), violence which is used by a state against civilians and non-state actors, and violence which is used by violent non-state actors against states and civilians. It can also describe politically motivated violence which is used by violent non-state actors against a state or it can describe violence which is used against other non-state actors and/or civilians. Non-action on the part of a government can also be characterized as a form of political violence, such as refusing to alleviate famine or otherwise denying resources to politically identifiable groups within their territory.

Anocracy, or semi-democracy, is a form of government that is loosely defined as part democracy and part dictatorship, or as a "regime that mixes democratic with autocratic features". Another definition classifies anocracy as "a regime that permits some means of participation through opposition group behavior but that has incomplete development of mechanisms to redress grievances." The term "semi-democratic" is reserved for stable regimes that combine democratic and authoritarian elements. Scholars distinguish anocracies from autocracies and democracies in their capability to maintain authority, political dynamics, and policy agendas. Anocratic regimes have democratic institutions that allow for nominal amounts of competition. Such regimes are particularly susceptible to outbreaks of armed conflict and unexpected or adverse changes in leadership.

Ethnic nationalism, also known as ethnonationalism, is a form of nationalism wherein the nation and nationality are defined in terms of ethnicity, with emphasis on an ethnocentric approach to various political issues related to national affirmation of a particular ethnic group.

Jay Ulfelder is an American political scientist who is best known for his work on political forecasting, specifically on anticipating various forms of political instability around the world. From 2001 to 2010, he served as research director of the Political Instability Task Force (PITF), which is funded by the Central Intelligence Agency. He is also the author of a book and several journal articles on democratization, democratic backsliding, and contentious politics.

Rare or extreme events are events that occur with low frequency, and often refers to infrequent events that have a widespread effect and which might destabilize systems. Rare events encompass natural phenomena, anthropogenic hazards, as well as phenomena for which natural and anthropogenic factors interact in complex ways.

The assessment of risk factors for genocide is an upstream mechanism for genocide prevention. The goal is to apply an assessment of risk factors to improve the predictive capability of the international community before the killing begins, and prevent it. There may be many warning signs that a country may be leaning in the direction of a future genocide. If signs are presented, the international community takes notes of them and watches over the countries that have a higher risk. Many different scholars, and international groups, have come up with different factors that they think should be considered while examining whether a nation is at risk or not. One predominant scholar in the field James Waller came up with his own four categories of risk factors: governance, conflict history, economic conditions, and social fragmentation.

Prevention of genocide is any action that works toward averting future genocides. Genocides take a lot of planning, resources, and involved parties to carry out, they do not just happen instantaneously. Scholars in the field of genocide studies have identified a set of widely agreed upon risk factors that make a country or social group more at risk of carrying out a genocide, which include a wide range of political and cultural factors that create a context in which genocide is more likely, such as political upheaval or regime change, as well as psychological phenomena that can be manipulated and taken advantage of in large groups of people, like conformity and cognitive dissonance. Genocide prevention depends heavily on the knowledge and surveillance of these risk factors, as well as the identification of early warning signs of genocide beginning to occur.

Benjamin Andrew Valentino is a political scientist and professor at Dartmouth College. His 2004 book Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the 20th Century, adapted from his PhD thesis and published by Cornell University Press, has been reviewed in several academic journals.

Below is an outline of articles on the academic field of genocide studies and subjects closely and directly related to the field of genocide studies; this is not an outline of acts or events related to genocide or topics loosely or sometimes related to the field of genocide studies. The Event outlines section contains links to outlines of acts of genocide.