Related Research Articles

In propositional logic, affirming the consequent, sometimes called converse error, fallacy of the converse, or confusion of necessity and sufficiency, is a formal fallacy of taking a true conditional statement, and invalidly inferring its converse, even though that statement may not be true. This arises when the consequent has other possible antecedents.

A false dilemma, also referred to as false dichotomy or false binary, is an informal fallacy based on a premise that erroneously limits what options are available. The source of the fallacy lies not in an invalid form of inference but in a false premise. This premise has the form of a disjunctive claim: it asserts that one among a number of alternatives must be true. This disjunction is problematic because it oversimplifies the choice by excluding viable alternatives, presenting the viewer with only two absolute choices when in fact, there could be many.

In classical rhetoric and logic, begging the question or assuming the conclusion is an informal fallacy that occurs when an argument's premises assume the truth of the conclusion. A question-begging inference is valid, in the sense that the conclusion is as true as the premise, but it is not a valid argument.

A syllogism is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true.

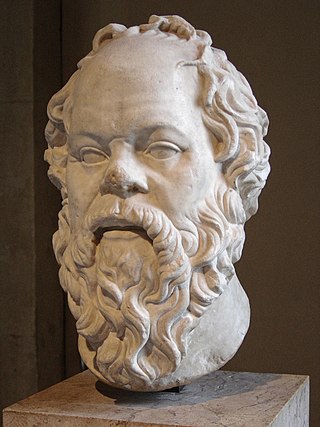

A fallacy is the use of invalid or otherwise faulty reasoning in the construction of an argument which may appear to be a well-reasoned argument if unnoticed. The term was introduced in the Western intellectual tradition by the Aristotelian De Sophisticis Elenchis.

In logic and formal semantics, term logic, also known as traditional logic, syllogistic logic or Aristotelian logic, is a loose name for an approach to formal logic that began with Aristotle and was developed further in ancient history mostly by his followers, the Peripatetics. It was revived after the third century CE by Porphyry's Isagoge.

The fallacy of the undistributed middle is a formal fallacy that is committed when the middle term in a categorical syllogism is not distributed in either the minor premise or the major premise. It is thus a syllogistic fallacy.

The fallacy of four terms is the formal fallacy that occurs when a syllogism has four terms rather than the requisite three, rendering it invalid.

A fallacy of illicit transference is an informal fallacy occurring when an argument assumes there is no difference between a term in the distributive and collective sense.

Illicit minor is a formal fallacy committed in a categorical syllogism that is invalid because its minor term is undistributed in the minor premise but distributed in the conclusion.

The fallacy of exclusive premises is a syllogistic fallacy committed in a categorical syllogism that is invalid because both of its premises are negative.

Tu quoque is a discussion technique that intends to discredit the opponent's argument by attacking the opponent's own personal behavior and actions as being inconsistent with their argument, therefore accusing hypocrisy. This specious reasoning is a special type of ad hominem attack. The Oxford English Dictionary cites John Cooke's 1614 stage play The Cittie Gallant as the earliest use of the term in the English language. "Whataboutism" is one particularly well-known modern instance of this technique.

Informal fallacies are a type of incorrect argument in natural language. The source of the error is not just due to the form of the argument, as is the case for formal fallacies, but can also be due to their content and context. Fallacies, despite being incorrect, usually appear to be correct and thereby can seduce people into accepting and using them. These misleading appearances are often connected to various aspects of natural language, such as ambiguous or vague expressions, or the assumption of implicit premises instead of making them explicit.

In logic, a categorical proposition, or categorical statement, is a proposition that asserts or denies that all or some of the members of one category are included in another. The study of arguments using categorical statements forms an important branch of deductive reasoning that began with the Ancient Greeks.

In philosophical logic, the masked-man fallacy is committed when one makes an illicit use of Leibniz's law in an argument. Leibniz's law states that if A and B are the same object, then A and B are indiscernible. By modus tollens, this means that if one object has a certain property, while another object does not have the same property, the two objects cannot be identical. The fallacy is "epistemic" because it posits an immediate identity between a subject's knowledge of an object with the object itself, failing to recognize that Leibniz's Law is not capable of accounting for intensional contexts.

In philosophy, a formal fallacy, deductive fallacy, logical fallacy or non sequitur is a pattern of reasoning rendered invalid by a flaw in its logical structure that can neatly be expressed in a standard logic system, for example propositional logic. It is defined as a deductive argument that is invalid. The argument itself could have true premises, but still have a false conclusion. Thus, a formal fallacy is a fallacy where deduction goes wrong, and is no longer a logical process. This may not affect the truth of the conclusion, since validity and truth are separate in formal logic.

A premise or premiss is a proposition—a true or false declarative statement—used in an argument to prove the truth of another proposition called the conclusion. Arguments consist of two or more premises that imply some conclusion if the argument is sound.

An argument is a statement or group of statements called premises intended to determine the degree of truth or acceptability of another statement called a conclusion. Arguments can be studied from three main perspectives: the logical, the dialectical and the rhetorical perspective.

In argumentation theory, an argumentum ad populum is a fallacious argument which is based on claiming a truth or affirming something is good because the majority thinks so.

References

- ↑ Chen, Raymond (26 February 2007). "The politician's fallacy and the politician's apology". The Old New Thing. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ↑ House of Commons (19 January 2005). Column 850: http://www.parliament.the-stationery-office.co.uk/pa/cm200405/cmhansrd/vo050119/debtext/50119-14.htm

- ↑ "Opposition Day — [2nd Allotted Day] — Protecting Children Online". House of Commons. 12 June 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ↑ Paul Krugman (12 December 2012). "The "Yes, Minister" Theory of the Medicare Age". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Joyce, George Howard (1908). Principles of Logic. Longmans. p. 205.