Related Research Articles

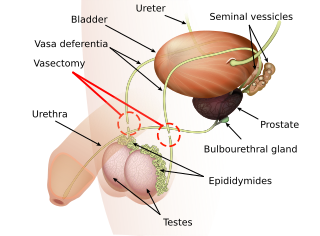

Vasectomy, is an elective surgical procedure for male sterilization or permanent contraception. During the procedure, the male vasa deferentia are cut and tied or sealed so as to prevent sperm from entering into the urethra and thereby prevent fertilization of a female through sexual intercourse. Vasectomies are usually performed in a physician's office, medical clinic, or, when performed on an animal, in a veterinary clinic. Hospitalization is not normally required as the procedure is not complicated, the incisions are small, and the necessary equipment routine.

Andrology is a name for the medical specialty that deals with male health, particularly relating to the problems of the male reproductive system and urological problems that are unique to men. It is the counterpart to gynaecology, which deals with medical issues which are specific to female health, especially reproductive and urologic health.

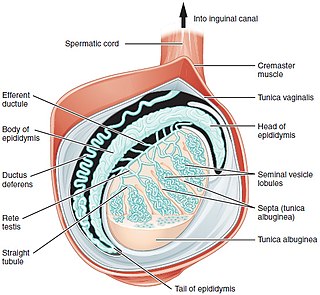

The vas deferens, with the more modern name ductus deferens, is part of the male reproductive system of many vertebrates. The ducts transport sperm from the epididymis to the ejaculatory ducts in anticipation of ejaculation. The vas deferens is a partially coiled tube which exits the abdominal cavity through the inguinal canal.

Epididymitis is a medical condition characterized by inflammation of the epididymis, a curved structure at the back of the testicle. Onset of pain is typically over a day or two. The pain may improve with raising the testicle. Other symptoms may include swelling of the testicle, burning with urination, or frequent urination. Inflammation of the testicle is commonly also present.

Spermatogenesis is the process by which haploid spermatozoa develop from germ cells in the seminiferous tubules of the testis. This process starts with the mitotic division of the stem cells located close to the basement membrane of the tubules. These cells are called spermatogonial stem cells. The mitotic division of these produces two types of cells. Type A cells replenish the stem cells, and type B cells differentiate into primary spermatocytes. The primary spermatocyte divides meiotically into two secondary spermatocytes; each secondary spermatocyte divides into two equal haploid spermatids by Meiosis II. The spermatids are transformed into spermatozoa (sperm) by the process of spermiogenesis. These develop into mature spermatozoa, also known as sperm cells. Thus, the primary spermatocyte gives rise to two cells, the secondary spermatocytes, and the two secondary spermatocytes by their subdivision produce four spermatozoa and four haploid cells.

Orchitis is inflammation of the testes. It can also involve swelling, pains and frequent infection, particularly of the epididymis, as in epididymitis. The term is from the Ancient Greek ὄρχις meaning "testicle"; same root as orchid.

Spermatocele is a fluid-filled cyst that develops in the epididymis. The fluid is usually a clear or milky white color and may contain sperm. Spermatoceles are typically filled with spermatozoa and they can vary in size from several millimeters to many centimeters. Small spermatoceles are relatively common, occurring in an estimated 30 percent of males. They are generally not painful. However, some people may experience discomfort such as a dull pain in the scrotum from larger spermatoceles. They are not cancerous, nor do they cause an increased risk of testicular cancer. Additionally, unlike varicoceles, they do not reduce fertility.

A varicocele is an abnormal enlargement of the pampiniform venous plexus in the male scrotum; the female equivalent of painful swelling to the embryologically identical pampiniform venous plexus is called pelvic compression syndrome. This plexus of veins drains blood from the testicles back to the heart. The vessels originate in the abdomen and course down through the inguinal canal as part of the spermatic cord on their way to the testis. Varicoceles occur in around 15% to 20% of all men. The incidence of varicocele increase with age.

Terms oligospermia, oligozoospermia, and low sperm count refer to semen with a low concentration of sperm and is a common finding in male infertility. Often semen with a decreased sperm concentration may also show significant abnormalities in sperm morphology and motility. There has been interest in replacing the descriptive terms used in semen analysis with more quantitative information.

Testicular pain, also known as scrotal pain, occurs when part or all of either one or both testicles hurt. Pain in the scrotum is also often included. Testicular pain may be of sudden onset or of long duration.

Testicular sperm extraction (TESE) is a surgical procedure in which a small portion of tissue is removed from the testicle and any viable sperm cells from that tissue are extracted for use in further procedures, most commonly intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) as part of in vitro fertilisation (IVF). TESE is often recommended to patients who cannot produce sperm by ejaculation due to azoospermia.

Chronic testicular pain is long-term pain of the testes. It is considered chronic if it has persisted for more than three months. Chronic testicular pain may be caused by injury, infection, surgery, cancer or testicular torsion and is a possible complication after vasectomy. IgG4-related disease is a more recently identified cause of chronic orchialgia.

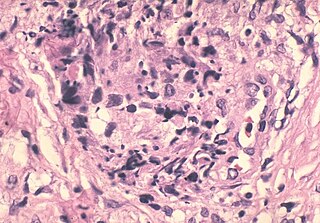

A sperm granuloma is a lump of leaked sperm that appears along the vasa deferentia or epididymides in vasectomized individuals. While the majority of sperm granulomas are present along the vas deferens, the rest of them form at the epididymis. Sperm granulomas range in size, from one millimeter to one centimeter. They consist of a central mass of degenerating sperm surrounded by tissue containing blood vessels and immune system cells. Sperm granulomas may also have a yellow, white, or cream colored center when cut open. While some sperm granulomas can be painful, most of them are painless and asymptomatic. Sperm granulomas can appear as a result of surgery, trauma, or an infection. They can appear as early as four days after surgery and fully formed ones can appear as late as 208 days later.

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS), previously known as chronic nonbacterial prostatitis, is long-term pelvic pain and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) without evidence of a bacterial infection. It affects about 2–6% of men. Together with IC/BPS, it makes up urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome (UCPPS).

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown cause that results in the formation of non-caseating granulomas in multiple organs. The prevalence is higher among black males than white males by a ratio of 20:1. Usually the disease is localized to the chest, but urogenital involvement is found in 0.2% of clinically diagnosed cases and 5% of those diagnosed at necropsy. The kidney is the most frequently affected urogenital organ, followed in men by the epididymis. Testicular sarcoidosis can present as a diffuse painless scrotal mass or can mimic acute epididymo-orchitis. Usually it appears with systemic manifestations of the disease. Since it causes occlusion and fibrosis of the ductus epididymis, fertility may be affected. On ultrasound, the hypoechogenicity and ‘infiltrative’ pattern seen in the present case are recognized features. Opinions differ on the need for histological proof, with reports of limited biopsy and frozen section, radical orchiectomy in unilateral disease and unilateral orchiectomy in bilateral disease. The peak incidence of sarcoidosis and testicular neoplasia coincide at 20–40 years and this is why most patients end up having an orchiectomy. However, testicular tumours are much more common in white men, less than 3.5% of all testicular tumours being found in black men. These racial variations justify a more conservative approach in patients of Afro-Caribbean descent with proven sarcoidosis elsewhere. Careful follow-up and ultrasonic surveillance may be preferable in certain clinical settings to biopsy and surgery, especially in patients with bilateral testicular disease.

Vasectomy reversal is a term used for surgical procedures that reconnect the male reproductive tract after interruption by a vasectomy. Two procedures are possible at the time of vasectomy reversal: vasovasostomy and vasoepididymostomy. Although vasectomy is considered a permanent form of contraception, advances in microsurgery have improved the success of vasectomy reversal procedures. The procedures remain technically demanding and may not restore the pre-vasectomy condition.

Reproductive surgery is surgery in the field of reproductive medicine. It can be used for contraception, e.g. in vasectomy, wherein the vasa deferentia of a male are severed, but is also used plentifully in assisted reproductive technology. Reproductive surgery is generally divided into three categories: surgery for infertility, in vitro fertilization, and fertility preservation.

Marc Goldstein, MD, DSc (hon), FACS is an American urologist and the Matthew P. Hardy Distinguished Professor of Reproductive Medicine, and Urology at Weill Cornell Medical College of Cornell University; Surgeon-in-Chief, Male Reproductive Medicine and Surgery; and Director of the Center of Male Reproductive Medicine and Microsurgery at the New York Presbyterian Hospital Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is Adjunct Senior Scientist with the Population Council's Center for Biomedical Research, located on the campus of Rockefeller University.

Antisperm antibodies (ASA) are antibodies produced against sperm antigens.

Fowler's syndrome is a rare disorder in which the urethral sphincter fails to relax to allow urine to be passed normally in younger women with abnormal electromyographic activity detected.

References

- 1 2 Potts JM (2008). "Post Vasectomy Pain Syndrome". Genitourinary Pain and Inflammation. Current Clinical Urology. Humana Press. pp. 201–209. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-126-4_13. ISBN 978-1-58829-816-4.

- 1 2 3 Nangia AK, Myles JL, Thomas AJ Jr (2000). "Vasectomy reversal for the post-vasectomy pain syndrome: a clinical and histological evaluation". J. Urol. 164 (6): 1939–42. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66923-6. PMID 11061886.

- ↑ Christiansen C, Sandlow J (2003). "Testicular Pain Following Vasectomy: A Review of Postvasectomy Pain Syndrome". Journal of Andrology. 24 (3): 293–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb02675.x . PMID 12721203.

- ↑ Manikandan R, Srirangam SJ, Pearson E, Collins GN (2004). "Early and late morbidity after vasectomy: a comparison of chronic scrotal pain at 1 and 10 years". BJU International. 93 (4): 93, 571–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2003.04663.x . PMID 15008732. S2CID 44286821.

- ↑ Awsare NS, Krishnan J, Boustead GB, Hanbury DC, McNicholas TA (2005). "Complications of vasectomy". Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 87 (6): 87: 406–410. doi:10.1308/003588405X71054. PMC 1964127 . PMID 16263006.

- ↑ "Vasectomy Guideline - American Urological Association". www.auanet.org. Retrieved 2022-04-30.

- ↑ Leslie, Thomas A.; Illing, Rowland O.; Cranston, David W.; Guillebaud, John (December 2007). "The incidence of chronic scrotal pain after vasectomy: a prospective audit". BJU International. 100 (6): 1330–1333. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07128.x . ISSN 1464-410X. PMID 17850378. S2CID 23328539.

- ↑ Choe, J. M.; Kirkemo, A. K. (April 1996). "Questionnaire-based outcomes study of nononcological post-vasectomy complications". The Journal of Urology. 155 (4): 1284–1286. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66244-X. ISSN 0022-5347. PMID 8632554.

- ↑ McMahon, A. J.; Buckley, J.; Taylor, A.; Lloyd, S. N.; Deane, R. F.; Kirk, D. (February 1992). "Chronic testicular pain following vasectomy". British Journal of Urology. 69 (2): 188–191. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.1992.tb15494.x. ISSN 0007-1331. PMID 1537032.

- ↑ Morris, Caroline; Mishra, K.; Kirkman, R. J. E. (July 2002). "A study to assess the prevalence of chronic testicular pain in post-vasectomy men compared to non-vasectomised men". The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 28 (3): 142–144. doi: 10.1783/147118902101196298 . ISSN 1471-1893. PMID 16259833. S2CID 15728585.

- ↑ Auyeung, Austin B.; Almejally, Anas; Alsaggar, Fahad; Doyle, Frank (January 2020). "Incidence of Post-Vasectomy Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17 (5): 1788. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051788 . PMC 7084350 . PMID 32164161.

- 1 2 Ahmed I, Rasheed S, White C, Shaikh N (1997). "The incidence of post-vasectomy chronic testicular pain and the role of nerve stripping (denervation) of the spermatic cord in its management". British Journal of Urology. 79 (2): 269–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.32221.x . PMID 9052481.

- ↑ Jarvis LJ, Dubbins PA (1989). "Changes in the epididymis after vasectomy: sonographic findings". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 152 (3): 531–4. doi:10.2214/ajr.152.3.531. PMID 2644777.

- ↑ Reddy NM, Gerscovich EO, Jain KA, Le-Petross HT, Brock JM (October 2004). "Vasectomy-related changes on sonographic examination of the scrotum". J Clin Ultrasound. 32 (8): 394–8. doi:10.1002/jcu.20058. PMID 15372447. S2CID 33127806.

- ↑ Schmidt S (1976). "Spermatic granuloma: an often painful lesion". Fertility and Sterility. 31 (2): 178–81. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)43819-7 . PMID 761679.

- ↑ Shapiro, Edward I.; Silber, Sherman J. (November 1979). "Open-Ended Vasectomy, Sperm Granuloma, and Postvasectomy Orchialgia". Fertility and Sterility. 32 (5): 546–550. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)44357-8 . PMID 499585.

- ↑ Shapiro EI, Silber SJ (November 1979). "Open-ended vasectomy, sperm granuloma, and postvasectomy orchialgia". Fertil. Steril. 32 (5): 546–50. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)44357-8 . PMID 499585.

- ↑ Selikowitz SM, Schned AR (1985). "A late post-vasectomy syndrome". The Journal of Urology. 134 (3): 494–7. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)47256-9. PMID 4032545.

- ↑ Myers SA, Mershon CE, Fuchs EF (1997). "Vasectomy reversal for treatment of the post-vasectomy pain syndrome". J. Urol. 157 (2): 518–520. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)65191-7. PMID 8996346.

- ↑ Pabst R, Martin O, Lippert H (1979). "Is the low fertility rate after vasovasostomy caused by nerve resection during vasectomy?". Fertility and Sterility. 31 (3): 316–320. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)43881-1 . PMID 437166.

- 1 2 Chen TF, Ball RY (1991). "Epididymectomy for post-vasectomy pain: histological review". Br. J. Urol. 68 (4): 407–413. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.1991.tb15362.x. PMID 1933163.